If you pick up a Bible today, you probably expect the list of the Old Testament books to be a fixed thing, like the periodic table or the roster of a baseball team. It isn't. Depending on whether you’re sitting in a Catholic cathedral, a Greek Orthodox parish, or a Baptist Sunday school, that list is going to look different. It's kinda wild when you think about it. We’re talking about the bedrock of Western civilization, and yet, the table of contents is still a point of debate for millions of people.

Most people just flip past the index. They shouldn't. The way these books are grouped—and which ones made the cut—tells a story about 2,000 years of theological bickering, translation hiccups, and cultural identity.

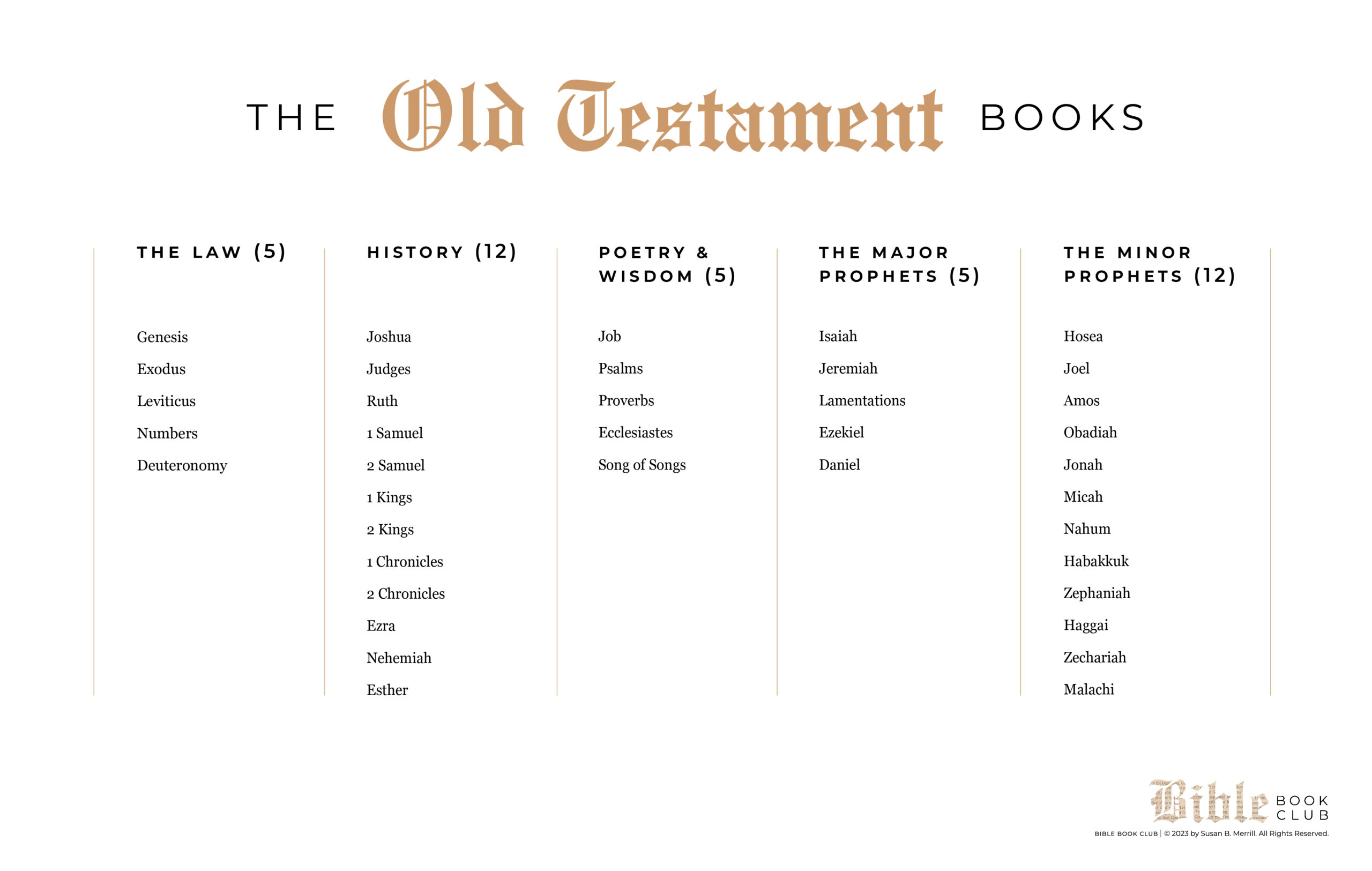

The Protestant Standard: 39 Books

Most English Bibles follow the Protestant canon. It’s the 39-book lineup that starts with Genesis and ends with Malachi. If you grew up in a non-Catholic environment, this is your baseline.

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. That’s the Torah, or the Pentateuch. It’s the foundation. From there, you jump into the "Historical Books." We're talking Joshua, Judges, Ruth, and the long chronicles of kings like David and Solomon. It reads like a gritty political drama sometimes. Then you hit the "Poetic Books"—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon. This is where the vibe shifts from "who conquered who" to "why is life so hard?" Finally, you’ve got the Prophets. Major ones like Isaiah and Jeremiah, and the twelve "Minor" ones like Amos or Micah.

Why 39?

Honestly, it’s because the Protestant Reformers, like Martin Luther, wanted to go back to the Hebrew sources. They looked at what the Jewish community in their day considered scripture—the Tanakh—and decided to stick with that. If it wasn't in the original Hebrew, Luther was skeptical. He even moved some books to a separate section called the Apocrypha, basically saying they were "good to read" but not on the same level as the rest. Eventually, many Protestant publishers just stopped printing those extra books to save money and space.

The Catholic and Orthodox Difference

Now, if you’re looking at a Catholic Bible, that list of the Old Testament books grows. You’ve suddenly got 46 books.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

What's the deal with the extra seven?

They’re called the Deuterocanonical books. Catholics call them that; Protestants call them the Apocrypha. This list includes Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (or Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and 1 and 2 Maccabees. There are also extra bits tacked onto Esther and Daniel.

These books weren't just pulled out of thin air. They were part of the Septuagint. That was the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures used by most Jews living outside of Israel during the time of Jesus. Since the early Christian church spoke Greek, that was their Bible. St. Augustine was a huge fan. He argued they should be included because the Church had always used them. It wasn't until the Council of Trent in the 1500s that the Catholic Church officially "locked in" this list as a direct response to the Reformation.

Eastern Orthodox traditions go even further. The Greek Orthodox Church includes 1 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has the longest list of all, including books like Enoch and Jubilees. If you’ve never read the Book of Enoch, it’s intense. It talks about giants and fallen angels in a way that feels more like Lord of the Rings than what you’d hear in a standard sermon.

Breaking Down the Sections

Instead of a boring list, let's look at how these books actually function. They aren't arranged chronologically. If you try to read the Bible from cover to cover thinking it's a linear timeline, you’re going to get very confused around the time you hit the Prophets.

The Law (The Pentateuch)

This is the "how-to" and "where we came from" section. Genesis covers the cosmic stuff—creation, the flood, the patriarchs. Then you get the legal codes in Leviticus. Honestly, Leviticus is where most "read the Bible in a year" plans go to die. It's dense. But for the original audience, these rules were about survival and identity.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

History (Joshua through Esther)

This is the rise and fall of Israel. It’s messy. You have heroes like Samson and villains like Jezebel. It covers the transition from tribal groups to a monarchy and then the eventual exile to Babylon.

Wisdom and Poetry

Psalms is basically an ancient songbook. Some are happy; some are literally people screaming at God for being unfair. Job is a philosophical debate about suffering. Proverbs is a collection of "street smarts." Ecclesiastes is surprisingly cynical, famously stating that "everything is meaningless." It’s the most "modern" sounding book in the whole collection.

The Prophets

Prophets weren't just fortune tellers. They were social critics. They were the ones yelling at kings for ignoring the poor. The "Major" and "Minor" labels just refer to the length of the scrolls, not their importance. Isaiah is huge (66 chapters); Obadiah is a single page.

Why the Order Matters

The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) actually uses the same "data" as the Protestant 39 books but orders them differently. It ends with 2 Chronicles, not Malachi.

Why does that matter?

Because the ending of a book changes the takeaway. Ending with Malachi creates a "to be continued" feeling that points directly to the New Testament and the arrival of John the Baptist. Ending with 2 Chronicles focuses on the return to the land of Israel and the rebuilding of the Temple. It’s the same text, but a different "vibe."

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The Books That Almost Didn't Make It

There were some close calls. For a long time, people debated whether the Song of Solomon should be in the list of the Old Testament books. Why? Because it’s an erotic love poem. There isn't much mention of God in it. It’s very... physical. Eventually, it stayed because it was interpreted as an allegory for God’s love for his people.

The book of Esther was also controversial because it doesn't mention God once. Not once. It’s a story of political maneuvering and bravery, but the divine is hidden behind the scenes.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re trying to study this stuff, don’t just memorize names. That’s boring and you’ll forget it in a week. Instead, understand the categories.

- Get a Study Bible that includes the Apocrypha. Even if you aren't Catholic, reading 1 Maccabees gives you the historical context for Hanukkah and the world Jesus was born into. It fills the "400 years of silence" between the Old and New Testaments.

- Read the Wisdom literature alongside the History. When you read about David’s life in 2 Samuel, flip over to the Psalms he supposedly wrote during those moments. It makes the "characters" feel like real people with actual emotions.

- Compare translations. Use a tool like BibleGateway to see how the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) handles a passage versus the King James (KJV). The NRSV is usually what scholars use, while the KJV is more for the poetic language.

- Identify the "Minor" Prophets' context. Most people ignore books like Nahum or Zephaniah. Pick one, look up when it was written, and see what the political situation was. Usually, they were responding to a specific crisis, like an impending invasion.

Understanding the list of the Old Testament books isn't about being a trivia master. It’s about realizing that this collection of literature is a library, not a single book. It’s a library built over a thousand years by dozens of authors, editors, and priests. Whether you're looking at the 39 books of the Protestant tradition or the 46 of the Catholic, you're looking at a map of how ancient people tried to make sense of their world, their suffering, and their God.

The next step for any serious reader is to stop looking at the table of contents and start looking at the internal links. Notice how the imagery in Genesis (like the Tree of Life) shows up again in the Prophets. That’s where the real depth is.