Walk down 6th Avenue today and you’ll see a fitness center. It’s clean. It’s quiet. It smells like eucalyptus and expensive sneakers. But if you were standing on that same corner of 20th Street in 1990, the vibe was… different. You’d be staring at the Limelight nightclub NYC, a place that felt less like a gym and more like a fever dream directed by a fallen angel.

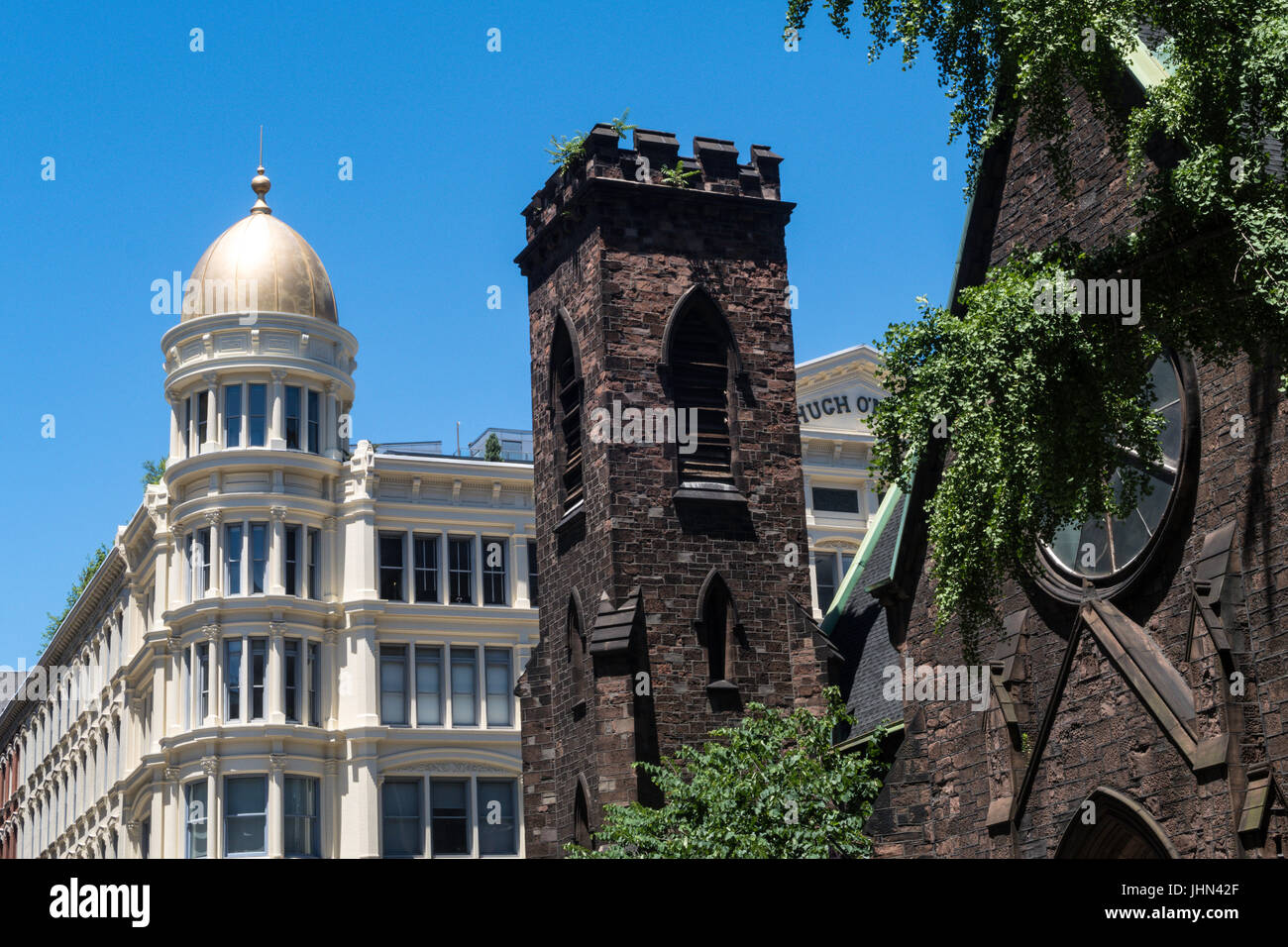

It was a church once. An Episcopal church built in the 1840s, specifically. Then Peter Gatien bought it.

Gatien, the guy with the infamous eye patch, had this weird, brilliant knack for turning hallowed ground into the epicenter of sin. People didn't just go there to dance. They went there to get lost. It was the flagship of an empire that included Tunnel and Palladium, but Limelight was the crown jewel because of that architecture. Imagine a thumping techno beat vibrating through stained-glass windows while a kid in a 7-foot-tall foam costume hands you a pill. That was Tuesday.

The Gatien Era and the Rise of the Club Kids

The Limelight nightclub NYC wasn't just about the music. Honestly, the music was often secondary to the theater of the whole thing. You had the Club Kids, led by Michael Alig and James St. James, who treated the gothic hallways like their personal runway. These weren't your typical VIPs. They weren't movie stars or Wall Street moguls—though those guys were definitely there, hiding in the shadows. No, the "stars" were teenagers from the suburbs who had transformed themselves into neon-colored monsters and celestial beings using glitter, hot glue, and a lot of imagination.

They weren't just "partying." They were performing.

Gatien gave them a platform. He understood that if you create a spectacle, the "normals" will pay any cover charge just to get a glimpse of it. But behind the glitter, things were getting dark. Fast. The club became synonymous with the 1990s rave scene, which meant it became the primary marketplace for a new generation of synthetic drugs. We aren't just talking about a little weed. We're talking about Special K, ecstasy, and GHB flowing like water through the pews.

When the Party Turned Into a Crime Scene

If you want to understand why the Limelight nightclub NYC is still talked about in hushed tones, you have to talk about Michael Alig. It's the part of the story everyone knows but nobody likes to dwell on. Alig was the king of the Club Kids, but his drug addiction turned him into something unrecognizable. In 1996, Alig and his roommate, Freeze, killed a drug dealer named Andre "Angel" Melendez.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

They did it in an apartment, not the club. But the shadow of that murder fell directly on the Limelight.

The story sounds like a bad horror movie: a dispute over money, a hammer, a box of Drano, and a dismembered body thrown into the Hudson River. For months, it was an open secret in the club scene. People were joking about it at the bar while the police were still looking for a missing person. It was the beginning of the end. Giuliani was already looking for a reason to "clean up" New York, and a brutal murder tied to the city's most famous nightclub gave him all the ammunition he needed.

The Legal War and the Eye Patch King

Peter Gatien was the ultimate target. The feds didn't just want the drug dealers; they wanted the man who owned the building. They claimed Gatien wasn't just aware of the drug sales—they claimed he facilitated them, essentially running a "drug supermarket."

It was a massive legal battle.

Gatien eventually beat the conspiracy charges in 1998, but the victory was hollow. The legal fees had drained him, and the city's "Quality of Life" campaign made it nearly impossible to keep the doors open. Every time a lightbulb was out of place or a fire exit was slightly blocked, the police were there to shut it down. It was a war of attrition. You can't run a nightclub when the police are literally stationed at the front door with clipboards every single night.

By the late 90s, the Limelight nightclub NYC was flickering. It closed, reopened as "Avalon," closed again, and eventually transitioned into a high-end retail space called the Limelight Marketplace. That didn't last either. New Yorkers didn't want to buy $80 candles in the same spot where they used to do bumps of ketamine. It felt wrong.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Why We Still Care About a Building on 20th Street

You might wonder why we’re still obsessing over a club that’s been dead for decades. It's because the Limelight represented the last gasp of "Old New York." Before the city became a playground for billionaires and safe, sanitized glass towers, it was gritty. It was dangerous. It was creative in a way that didn't require a corporate sponsor.

The Limelight was a microcosm of that chaos.

- The Architecture: You can't replicate the vibe of a 19th-century church. The acoustics were weird, the rooms were cramped, and the "VIP" area was often just a dusty organ loft.

- The Diversity: On a Friday night, you’d see drag queens, Wall Street bankers, punk rockers, and tourists from Ohio all crammed into the same space.

- The Mythos: Every person who went there has a story that sounds like a lie. "I saw Björk dancing with a guy dressed as a giant lobster." In the Limelight, that was probably true.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Scene

There's this idea that the Limelight was just a drug den. That’s a massive oversimplification.

Was there a lot of drug use? Obviously. But for many of the kids who spent their lives there, it was a sanctuary. If you were a queer kid from a small town who felt like an alien, the Limelight was the one place where being an alien made you royalty. It was a community. A dysfunctional, drug-fueled, chaotic community, but a community nonetheless.

When people talk about the "death of nightlife," they aren't talking about the absence of bars. They're talking about the absence of spaces that feel like they belong to the freaks.

Today, the building houses David Barton Gym. It’s ironic, really. People are still going there to transform their bodies, but instead of glitter and chemical enhancements, they’re using HIIT workouts and protein shakes. The stained glass is still there. The gothic arches still loom overhead. If you're running on a treadmill and the light hits the floor just right, you can almost see the ghosts of the 90s shimmering in the dust.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Realities of the Legacy: A Timeline of Chaos

- 1983: Peter Gatien opens Limelight in the former Holy Communion Church.

- Early 90s: The "Disco 2000" nights become the peak of Club Kid culture.

- 1996: The murder of Angel Melendez sends shockwaves through the scene.

- 1998: Gatien is acquitted of federal drug conspiracy charges but faces massive tax issues.

- 2001-2003: The club struggles under various names, including Avalon, before finally losing its luster.

- 2010: The building reopens as a "festival of shops" (it fails).

- Present: It functions primarily as a high-end fitness center and event space.

How to Experience the Limelight Legacy Today

You can’t go back to 1992. You probably wouldn't want to, honestly—the bathrooms were a nightmare and the air was 40% secondhand smoke. But you can still touch the history.

Visit the Building

Go to 656 Avenue of the Americas. You can walk right in. It’s a gym now, but the bones of the church are intact. Look up. The ceiling height alone tells you why it was the perfect place for a party.

Watch the Documentaries

If you want the unvarnished truth, watch Party Monster: The Shockumentary or the feature film Party Monster starring Macaulay Culkin. For a more business-focused look at the rise and fall of Peter Gatien, Limelight (the 2011 documentary) is essential viewing. It features Gatien himself explaining how he built the empire.

Read the Memoirs

James St. James’s book Disco Bloodbath is the definitive account of the era. It’s witty, horrifying, and incredibly well-written. It captures the "voice" of the scene better than any news report ever could.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Explorer

If you’re looking to find the "spirit" of the Limelight nightclub NYC in today’s world, you have to look outside of Manhattan. The days of giant, church-sized clubs in Chelsea are over due to real estate prices and zoning laws.

- Look to Brooklyn: Neighborhoods like Bushwick and Ridgewood are where the DIY spirit lives now. Places like House of Yes carry the torch of costumed performance and radical inclusion that the Club Kids pioneered.

- Understand the Risks: The history of the Limelight serves as a cautionary tale. It shows how quickly a creative movement can be swallowed by substance abuse and how easily "the man" can shut down a scene once it becomes a liability.

- Appreciate the Architecture: Next time you see a historic building being repurposed, think about what it used to be. The Limelight taught us that the "soul" of a building changes based on who holds the keys.

The era of the mega-club is dead, replaced by curated "experiences" and TikTok-friendly lounges. But for a few wild years, a deconsecrated church in the middle of New York City was the most important place on Earth for anyone who didn't fit in. It was messy. It was illegal. It was beautiful. And it will never happen again.

If you want to dive deeper into the legal documents or the specific architectural history of the site, checking the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission's archives for the Church of the Holy Communion will give you the technical specs of the building before it became the world's most famous party. Just don't expect to find any mention of Michael Alig in the blueprints.

The Limelight is a ghost now. But in New York, the ghosts are often more interesting than the living. Enjoy the history, but maybe keep your eyes open the next time you're in a gym—you never know who might be lurking in the shadows of those stained-glass windows.