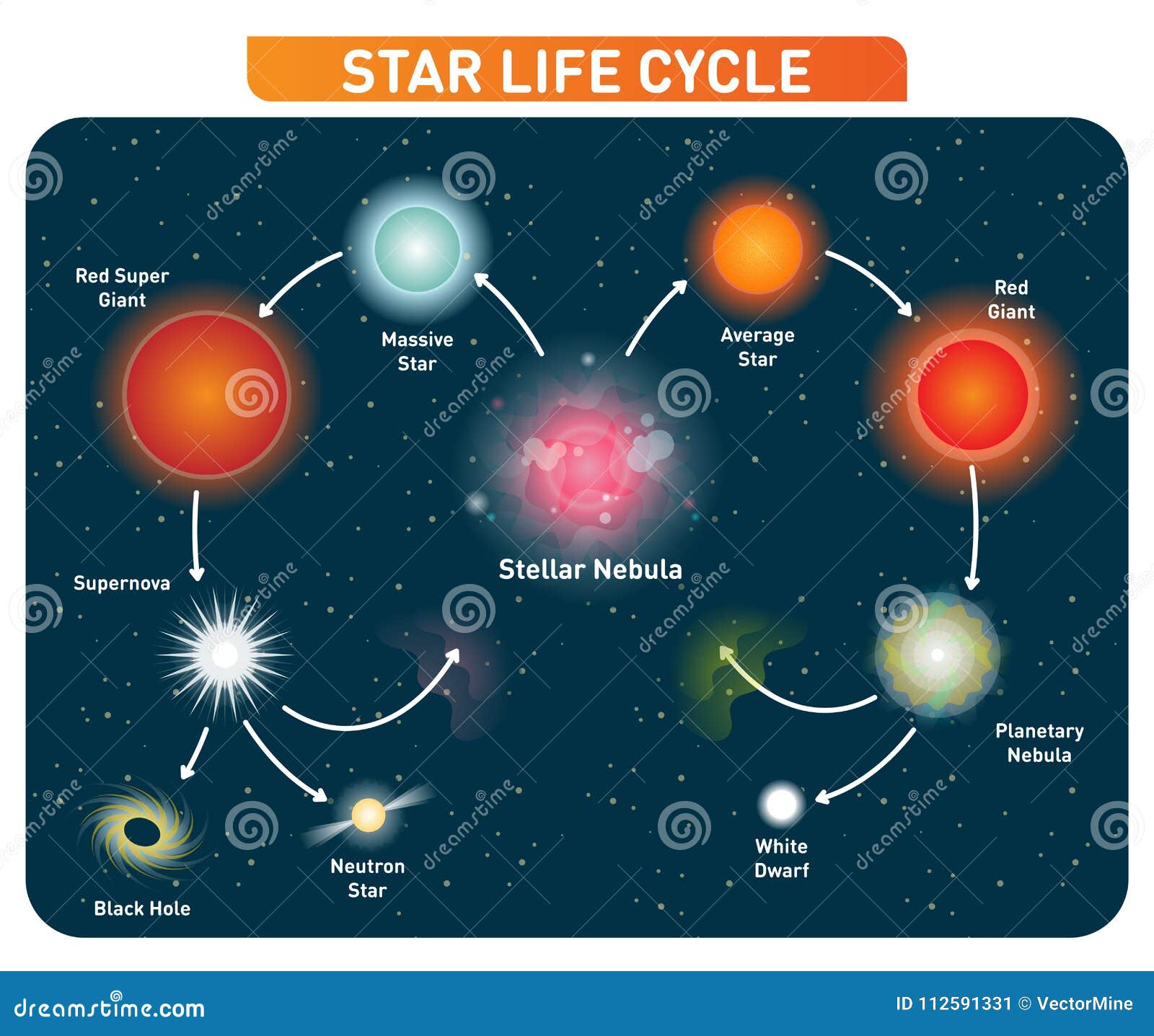

Space is violent. We look up at the night sky and see these steady, twinkling points of light, but it’s actually a graveyard of nuclear furnaces and screaming gas clouds. If you’ve ever looked at a diagram of life cycle of a star, you probably saw a neat little flowchart. It starts with a cloud, moves to a sun-like ball, and ends in a black hole or a white dwarf. Clean. Simple. Linear.

But honestly? It’s a mess.

The universe doesn't follow a straight line. Stars are basically just a constant, multi-billion-year struggle between gravity trying to crush everything into a point and nuclear fusion trying to blow everything apart. When one of those forces wins, things get weird. Most people think our Sun is "average." It’s not. It’s actually in the top 10% of stars by mass. Most stars in the galaxy are tiny, dim red dwarfs that will live for trillions of years—longer than the current age of the universe.

Where the Diagram of Life Cycle of a Star Actually Begins

Everything starts in a Giant Molecular Cloud (GMC). Think of it as a massive, cold nursery. These things are huge, spanning hundreds of light-years, and they’re mostly hydrogen. But they aren't just sitting there. They need a "kick" to get started. Maybe a nearby supernova shockwave hits the cloud, or two galaxies bump into each other.

Once that happens, gravity takes over. The cloud fragments.

This is where you get a protostar. It’s not a star yet. It’s just a hot, glowing ball of gas that’s still gathering mass. It’s "pre-main sequence." If it doesn't get big enough—specifically, if it doesn't reach about 8% of the Sun’s mass—it becomes a "failed star" or a brown dwarf. These are the runts of the litter. They’re too big to be planets but too small to ignite hydrogen fusion.

✨ Don't miss: Why Use a YT Video Tags Extractor? What Most People Get Wrong

The Main Sequence: The Long Middle

Once the core hits about 15 million degrees Celsius, hydrogen atoms start smashing together to form helium. This is fusion. This is the "Main Sequence" phase, and it's where stars spend about 90% of their lives.

Our Sun is here right now. It’s been here for 4.6 billion years. It’ll be here for another 5 billion. But here’s the kicker: the bigger the star, the shorter it lives. A massive O-type star might burn through its fuel in a few million years. A tiny red dwarf? It sips its fuel so slowly it could theoretically live for 10 trillion years.

The Fork in the Road: Low-Mass vs. High-Mass

This is where your diagram of life cycle of a star usually splits into two paths. The destiny of a star is determined entirely by how much "stuff" it started with. Mass is destiny in astrophysics.

Small and Medium Stars (The Sun’s Path)

When a star like ours runs out of hydrogen in its core, it doesn't just go out. It panics. Gravity starts winning, crushing the core, which actually makes it hotter. This heat pushes the outer layers out. The star swells. It becomes a Red Giant.

Eventually, the outer layers just drift away into space, creating a planetary nebula. These are some of the most beautiful objects in the sky, like the Ring Nebula or the Helix Nebula. What’s left behind is the core: a White Dwarf. It’s about the size of Earth but has the mass of the Sun. One teaspoon of white dwarf material would weigh as much as an elephant.

Massive Stars (The Fireworks)

If a star is more than about 8 times the mass of the Sun, it doesn't go quietly. It creates heavier and heavier elements in its core: Helium to Carbon, then Neon, Oxygen, Silicon, and finally—Iron.

✨ Don't miss: Apple Store Boulder Colorado 29th Street: Why It Still Matters in a Digital World

Iron is the "poison" for stars.

Fusing iron doesn't create energy; it consumes it. The moment iron is created in the core, the outward pressure vanishes. In less than a second, the entire star collapses inward at a fraction of the speed of light and then bounces off the core.

Supernova.

The Ghostly Afterlife: Neutron Stars and Black Holes

After the explosion, what’s left? If the remaining core is between 1.4 and 3 times the Sun’s mass, it becomes a Neutron Star. This is basically a giant atomic nucleus. If it’s even heavier, gravity wins completely. Not even light can escape. You get a Black Hole.

📖 Related: F-117 Stealth Fighter: Why the Wobbly Goblin is Still Flying in 2026

People often ask if the Sun will become a black hole. No. It's not fat enough. It’ll just be a cold, lonely lump of carbon (a black dwarf) eventually.

Why This Matters for You

You are literally made of star bits. Every atom of oxygen you breathe, the calcium in your teeth, and the iron in your blood was forged inside the heart of a dying star or in the heat of a supernova. Understanding the diagram of life cycle of a star isn't just about pretty pictures in a textbook; it’s an anatomy lesson for the human race.

We are the universe looking back at itself.

How to Use This Knowledge Today

If you want to actually see this cycle in action without a PhD, start with these steps:

- Get a Pair of Binoculars: You don't need a $2,000 telescope. A decent pair of 10x50 binoculars will show you the Orion Nebula (a stellar nursery) and the Pleiades (young stars).

- Download a Star Map App: Use something like SkyGuide or Stellarium. Look for "Betelgeuse" in the constellation Orion. It’s a red supergiant that could go supernova tomorrow—or in 100,000 years. It's basically a "dead star walking."

- Follow NASA’s JWST Updates: The James Webb Space Telescope is currently peer-pressuring the earliest stars in the universe to give up their secrets. Their images of "Star-forming regions" are the highest-resolution versions of the start of the life cycle we've ever seen.

- Visit a Dark Sky Park: Light pollution kills the view. Find an International Dark Sky Park near you to see the Milky Way. That hazy band of light is millions of stars at every single stage of the diagram mentioned above.

The cycle continues. Old stars die, seeding the galaxy with heavy elements, which then clump together to form new stars and planets. This is the cosmic recycling program that made Earth possible.