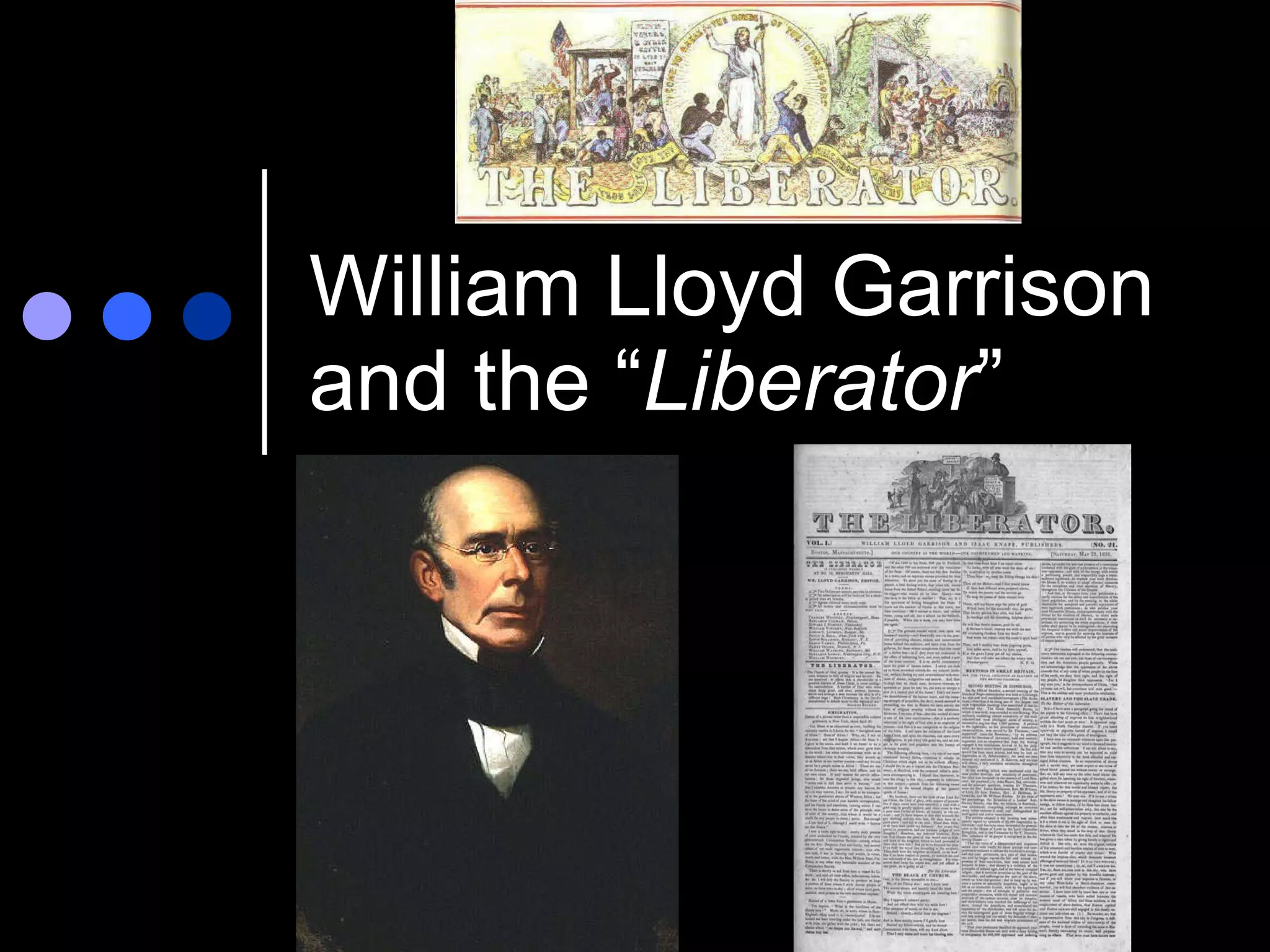

On January 1, 1831, a thirty-something guy with spectacles and a receding hairline walked into a tiny, cramped office in Boston. He didn't have much money. He didn't have a massive political machine backing him. What he had was a printing press and a level of audacity that, honestly, most people at the time found completely terrifying. That man was William Lloyd Garrison, and the first issue of The Liberator newspaper was about to change everything.

He didn't start small. He didn't ask for "gradual" change. In that very first issue, he wrote some of the most famous words in American history: "I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD."

He was heard, alright. But not everyone liked what they were hearing. In fact, for most of its thirty-five-year run, The Liberator newspaper William Lloyd Garrison published was considered a "radical" rag that many blamed for tearing the country apart. If you think social media is polarized today, you haven't seen 1830s Boston.

The Radical Idea of "Immediate Emancipation"

You have to understand the context of the 1830s to realize how wild Garrison’s stance actually was. Back then, even most people who were "against" slavery were part of the American Colonization Society. Their "solution" was basically to send formerly enslaved people back to Africa. It was a "not in my backyard" approach to morality.

Garrison hated that. He thought it was a scam.

To him, slavery wasn't just a political problem or an economic "peculiarity" of the South. It was a "covenant with death and an agreement with hell." He demanded immediate emancipation. No waiting. No compensating the slave owners for their "lost property." No shipping people off to Liberia. Just stop it. Right now.

It's hard to overstate how much this pissed people off. In the North, business owners who relied on Southern cotton thought he was a threat to the economy. In the South, his newspaper was basically treated like contraband. The state of Georgia actually offered a $5,000 reward for his arrest. That’s about $170,000 in today’s money just for a guy who ran a weekly paper with a relatively small circulation.

📖 Related: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

How The Liberator Newspaper William Lloyd Garrison Ran Actually Worked

The paper wasn't a massive corporate operation. It was scrappy. For the first few years, Garrison and his partner Isaac Knapp literally slept on the floor of the printing office. They ate bread and milk. It was the 19th-century version of a garage startup, but instead of coding apps, they were dismantling an institutional evil.

Surprisingly, the majority of the paper’s subscribers weren't white Northern liberals. They were free Black Americans. Early on, about three-quarters of the readers were Black. They were the ones funding the movement when the rest of white society was calling Garrison a fanatic.

- Circulation stayed low: It rarely topped 3,000 copies.

- Impact was huge: Because it was so controversial, other papers would reprint Garrison’s editorials just to argue with him, which accidentally spread his message to hundreds of thousands of people.

- The Format: It was a four-page weekly. No photos, just dense columns of type that people would read out loud in barber shops, churches, and community centers.

Garrison wasn't just the editor; he was the primary voice. He used a "moral suasion" strategy. Basically, he believed if you just showed people how evil slavery was, their consciences would eventually snap. He published harrowing accounts of the internal slave trade. He gave a platform to people like Frederick Douglass before Douglass was a household name. In fact, it was Garrison who first heard Douglass speak at a convention in Nantucket and told him, "You need to write this down."

When Things Got Violent

Living as the face of The Liberator newspaper William Lloyd Garrison meant living with a target on your back. In 1835, a "broadcloth mob" (basically a bunch of wealthy guys in fancy suits) dragged Garrison through the streets of Boston with a rope around his waist. They were going to lynch him. He only survived because the mayor locked him in jail for his own "protection."

Imagine that. You’re the one being attacked, and you end up in a cell because the city can’t control the people trying to kill you.

Garrison’s response? He went right back to the press. He didn't care about "civility" if civility meant staying silent about human trafficking. He famously burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution in public because it protected slavery. He called it a "stained" document. If you think people get mad about flag burning today, imagine the reaction to that in 1854.

👉 See also: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

The Gender Rebellion Inside the Paper

The paper wasn't just about abolition. Garrison was also a massive supporter of women’s rights, which actually caused a huge split in the abolitionist movement. A lot of men were fine with ending slavery but were definitely not fine with women like Sarah and Angelina Grimké speaking in public.

Garrison didn't budge. He opened the pages of The Liberator newspaper to women’s voices. He argued that if you’re fighting for human rights, you can’t exactly exclude half the human race. This led to the "Great Schism" of 1840, where the movement basically broke in two. Garrison stayed on the "radical" side, insisting that every form of oppression was linked.

Why the Paper Eventually Stopped

A lot of people think Garrison just kept writing until he died. Not quite. He was actually very specific about his mission. When the 13th Amendment was ratified in 1865, officially ending slavery in the United States, Garrison decided his job was done.

He printed the final issue of The Liberator newspaper on December 29, 1865.

His friends, including Frederick Douglass, actually disagreed with him. They argued that "slavery is not abolished until the Black man has the ballot." They knew that legal freedom was just the start and that Jim Crow was lurking around the corner. Garrison, however, felt that the specific purpose of his paper—the immediate destruction of the legal institution of slavery—had been met. He was tired. He had been doing this for thirty-five years under constant threat of death.

What Most People Get Wrong About Garrison

There’s this idea that Garrison was a "white savior" character. If you look at the actual history of The Liberator newspaper, it's more like he was a megaphone for a movement that was already happening in Black communities. He didn't "invent" abolitionism. He just refused to be polite about it.

✨ Don't miss: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

He was also a pacifist. This is the weird contradiction of Garrison: he used incredibly violent, aggressive language in his writing, but he was a "non-resistant." He didn't believe in using physical force, even in self-defense. When John Brown raided Harpers Ferry, Garrison was torn. He admired Brown’s spirit but couldn't get behind the violence.

Actionable Insights from the Garrison Era

Studying the life of William Lloyd Garrison and his newspaper isn't just a history lesson; it's a blueprint for how media can actually drive social change. If you're looking to understand how to move the needle on a "fringe" idea until it becomes mainstream, Garrison is the case study.

1. Identify the "Unacceptable" Compromise

Garrison succeeded because he refused to accept the "middle ground" of colonization or gradualism. If an issue is a moral one, find the absolute core truth and refuse to hedge. In your own advocacy or communication, identify where you are "equivocating" just to be liked.

2. Build a Community of "Outsiders"

The paper survived because of the Black community in the North. It didn't need the approval of the Boston elite. If you’re starting a movement or a brand, don't worry about the "mass market" first. Focus on the people who are most affected by the problem you're solving.

3. Use the Opposition's Megaphone

Garrison knew that when his enemies quoted him to mock him, they were still spreading his ideas. Don't be afraid of "bad press" if it means your core message is reaching a wider audience. Controversy is a tool, as long as it's backed by a consistent moral framework.

4. Know When the Mission is Met

One of the hardest things for any leader is knowing when to close the doors. Garrison’s decision to end the paper in 1865 is a lesson in focus. By ending the paper when the 13th Amendment passed, he preserved the legacy of the publication as a successful tool for a specific revolution.

To really get the full picture, you should look into the digital archives of the Boston Public Library, which has scanned many original issues of the paper. Reading the original advertisements and the "Refuge of Oppression" column (where Garrison would reprint pro-slavery articles just to dunk on them) gives you a visceral sense of the 19th-century culture war.

If you want to understand the modern American protest tradition, you have to start with the man who refused to "retreat a single inch." Garrison’s legacy isn't just that he helped end slavery, but that he proved a single, persistent voice—even one operating out of a tiny, messy office—can eventually force a whole nation to look in the mirror.