Jane Austen didn't spend her whole life staring out a window at a rainy English garden, waiting for a proposal that would change her world. If you read the letters of Jane Austen, you find a woman who was sharp, occasionally mean, obsessed with the price of tea, and deeply invested in the quality of her own stockings.

Most people come to these letters expecting Mr. Darcy. Instead, they get a woman talking about how she’s "drank too much wine" or how a neighbor’s new hat is absolutely hideous. It’s better than the novels, honestly. It’s real.

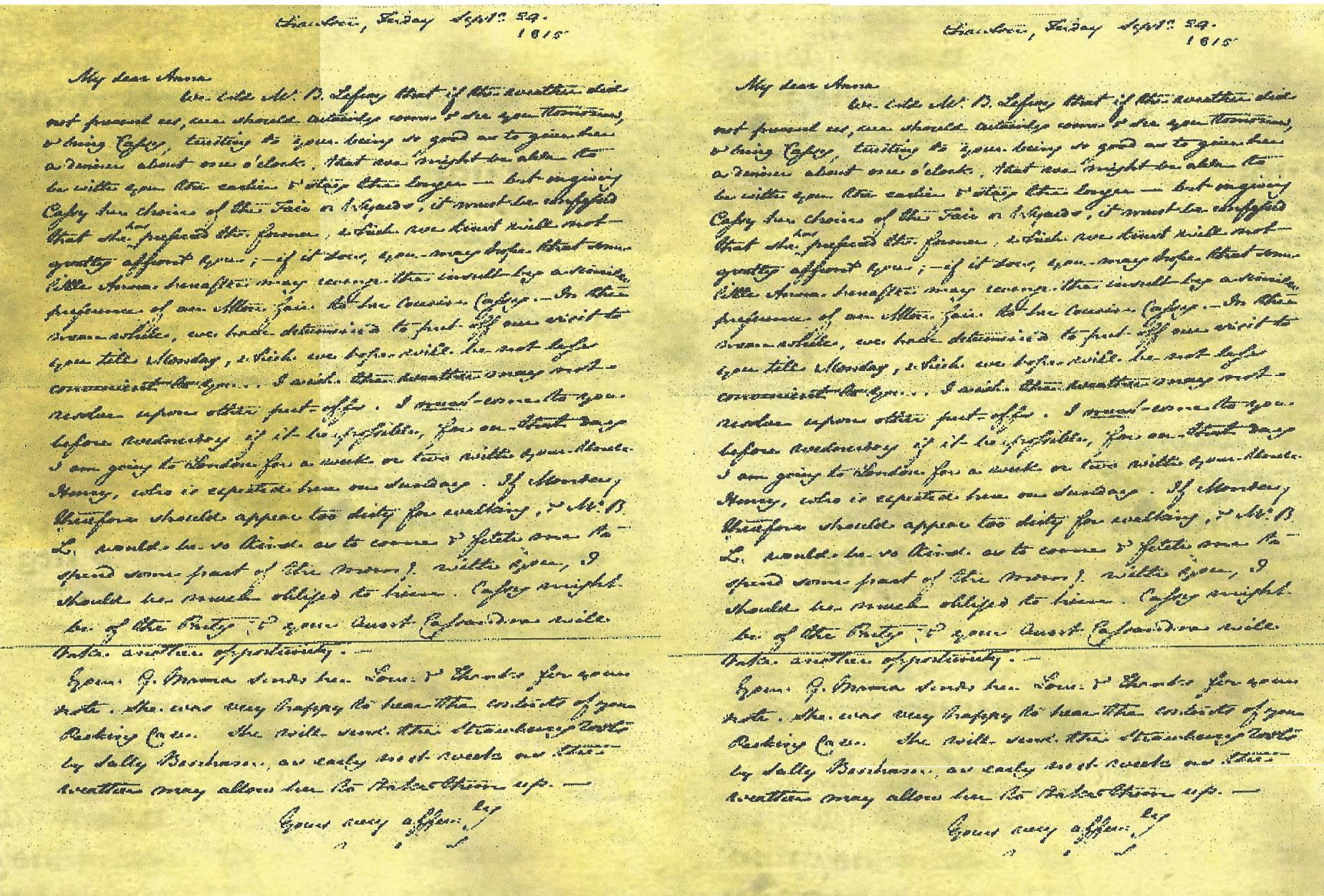

The tragedy, of course, is that we only have a fraction of what she actually wrote. Her sister Cassandra, in a move that historians still haven’t quite forgiven, burned the vast majority of Jane’s correspondence after her death in 1817. She wanted to protect Jane’s reputation. She wanted to hide the "sharpness" that didn't fit the image of a Victorian maiden aunt. But what survived—roughly 160 letters out of perhaps thousands—is a goldmine of Georgian sass and domestic reality.

The Myth of the "Dear Aunt Jane"

We have this sterilized version of Austen. People think of her as this quiet, observational creature. But when you dive into the letters of Jane Austen, you meet someone who could be brutally funny. Writing to Cassandra in 1798, she remarks on a woman at a ball: "Mrs. Hall, of Sherborne, was brought to bed yesterday of a dead child, some weeks before she expected, owing to a fright. I suppose she happened unawares to look at her husband."

Ouch.

That isn't the voice of a soft-hearted romantic. That’s a woman with a razor-blade wit. Scholars like Deidre Le Faye, who spent a lifetime editing and dating these letters, have pointed out that Jane used her correspondence as a testing ground for her prose. She was practicing. She was experimenting with rhythm and tone.

You’ve probably seen the movies where she's always writing by candlelight with a quill. In reality, she was writing while managing the household flour supply. The letters are obsessed with money. She tracks every shilling. She discusses the cost of lace, the price of butter, and the annoying necessity of buying a new carriage. For a woman of her social standing, these weren't just trivialities; they were the boundaries of her freedom.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

What happened to the "missing" letters?

The gap in her correspondence is massive. We have a lot from her early years and her final years, but the middle is a bit of a black hole. Cassandra Austen didn't just burn letters; she literally cut pieces out of them with scissors. If Jane said something too scandalous about a relative or expressed too much grief over her failed "romance" with Tom Lefroy, it went into the fireplace.

Imagine if your sibling deleted 90% of your texts after you died to make you look "nicer." That’s what we’re dealing with here.

Living through the Letters of Jane Austen

If you want to understand the Georgian era, stop reading history books and just read Jane’s complaints about travel. Travel sucked. It was slow, muddy, and expensive.

She writes about the physical exhaustion of moving from Steventon to Bath. She didn't even want to move to Bath. Legend says she fainted when she heard the news. In her letters, the city comes across as a place of endless, tiring social obligations. She’s constantly "on display" in a way that she clearly finds draining.

But there’s also the joy. She loved her brother Edward’s estate at Chawton. It was there, in that small cottage, that her writing truly exploded. The letters from the Chawton years are filled with the business of publishing. She talks about the "proofs" of Sense and Sensibility. She worries about the "vile" printers. She celebrates making her own money.

Money is the heartbeat of the letters of Jane Austen. She wasn't writing for "art's sake" alone; she wanted to be paid. She was a professional.

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

The Tom Lefroy Mystery

Everyone wants to know about the "one that got away." In 1796, Jane wrote to Cassandra about a young Irishman named Tom Lefroy. She describes him as a "very gentlemanlike, good-looking, pleasant young man." They flirted. They danced. She joked about expecting a proposal.

Then, he was gone. His family moved him away because she wasn't rich enough.

People search these letters for signs of a broken heart. You won’t find a melodramatic breakdown. You find a woman who simply moves on—or at least, pretends to. A few years later, she’s writing about someone else or laughing about a ball. It’s a lesson in Georgian stoicism. Or maybe it’s just that Cassandra burned the letters where Jane actually cried. We'll never know.

Why the tone shifts toward the end

As she got older, and especially as she got sicker (likely with Addison’s Disease or Hodgkin’s Lymphoma), the letters changed. The "sharpness" softened into a deep, protective love for her nieces, particularly Fanny Knight.

She gave relationship advice. It’s some of the most famous content in the letters of Jane Austen. To Fanny, who was wavering on a suitor, Jane wrote: "Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without affection."

This is the woman who never married. She turned down Harris Bigg-Wither after a single night of engagement because she realized she couldn't stomach a life without love, even if it meant financial insecurity. The letters reflect that integrity. Even when she’s dying, her concern is for the people she’s leaving behind, particularly her mother and Cassandra.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

The practical reality of reading them today

Reading the letters isn't like reading a novel. It can be confusing. She mentions dozens of "Cousin Williams" and "Mrs. Smiths" without context because, well, she was writing to her sister who knew everyone.

- Use an annotated version. Don't try to read them raw.

- Look for the 4th edition edited by Deidre Le Faye. It's the gold standard.

- Don't read them in order. Dip in.

- Find the letters from 1813. That's when Pride and Prejudice was taking off. Her excitement is contagious.

She calls Pride and Prejudice her "own darling child." She talks about Elizabeth Bennet as if she were a real person. That’s the magic. You aren't just reading a historical document; you’re eavesdropping on a genius talking to her best friend.

How to actually start exploring Jane's world

If you’re ready to move past the movies and see the real woman, you need to be strategic. The letters of Jane Austen can be dense, but they are the only way to hear her actual voice without the filter of a narrator.

1. Focus on the Chawton years first. Start with the letters from 1809 to 1817. This is the peak of her career. You get the behind-the-scenes gossip of her novels being published. It’s the most "literary" part of her correspondence.

2. Track the "Sass." Search for her comments on neighbors and social events. It’s where her character sketches for the novels began. You’ll see the DNA of Mr. Collins or Mrs. Bennet in the real people she met at local assemblies.

3. Visit the Jane Austen’s House website. They often feature digital scans of the original manuscripts. Seeing her handwriting—small, neat, and economizing every inch of the paper (stamps were expensive!)—changes how you perceive her. She used "cross-writing," where she wrote horizontally and then vertically over the same page to save space.

4. Compare the letters to the novels. Read her descriptions of Bath in her letters versus how she describes it in Northanger Abbey or Persuasion. The letters are often much grittier.

The letters aren't just for scholars. They are for anyone who has ever felt a bit out of place at a party or worried about their bank account. They reveal a woman who was profoundly human, occasionally frustrated, but always, always sharp-witted. She wasn't a saint. She was a writer.