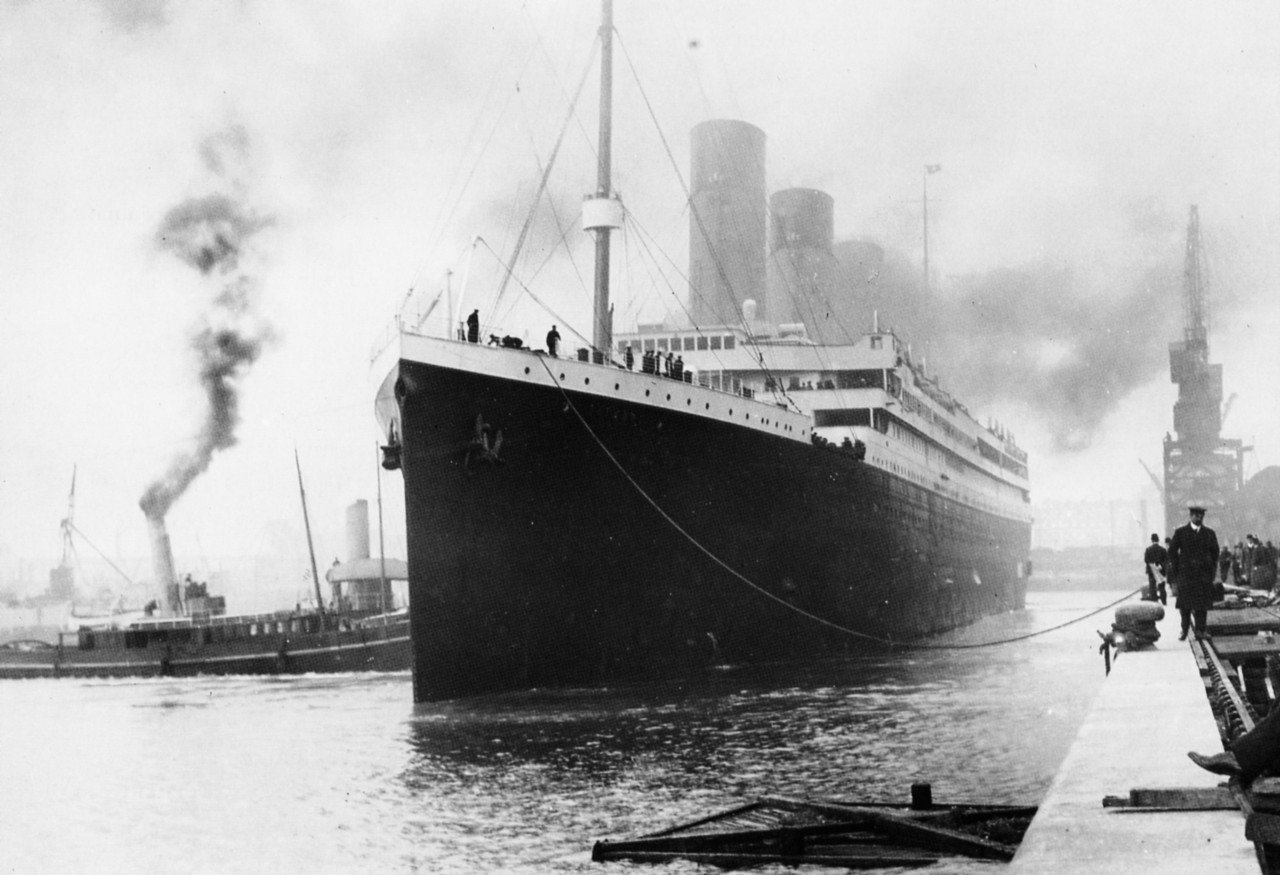

It is a grainy, somewhat haunting image. You’ve probably seen it while scrolling through late-night history threads or tucked away in a museum exhibit. It shows the massive hull of the RMS Titanic, smoke billowing from its stacks, moving away from the Irish coast. For over a century, this image—the last photo of Titanic—has served as a visual period at the end of a sentence that the world is still trying to finish.

But history is rarely as tidy as a single photograph.

When we talk about the last photo of Titanic, we aren't just talking about a piece of film. We’re talking about Father Francis Browne. He was a Jesuit novice who traveled on the first legs of the voyage from Southampton to Cherbourg, and finally to Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland. He took dozens of photos. Then, he got off. It was a stroke of luck that feels almost supernatural in hindsight, but for us, it meant the only high-quality record of life on board survived the sinking.

The moment the shutter clicked for the final time

The ship was leaving Queenstown. It was April 11, 1912.

The anchor had been raised. The tenders, Ireland and America, had finished ferrying the final passengers and mail to the massive liner. As the Titanic began to steam toward the open Atlantic, headed for New York, a few people on the shore and on the departing tenders pointed their cameras.

The "official" last photo of Titanic is generally attributed to John Morrogh. He was standing on the pier at Crosshaven as the ship moved into the distance. It’s a side profile. The ship looks invincible. It looks like a mountain of steel. Most people find it chilling because of the scale; the Atlantic looks so vast, and even the world’s largest ship looks like a toy against the horizon.

There is another contender, though. Some historians point to a photograph taken from the tender America by a passenger who had just disembarked. In this shot, you can see the wake of the ship. It’s moving. It’s leaving. Honestly, that’s the one that gets me. It isn't a static portrait. It is an action shot of a doomed object.

Why do we care so much about a blurry ship?

Morbid curiosity? Maybe. But I think it's deeper.

We live in a world where everything is recorded. If the Titanic sank today, there would be 2,000 TikTok livestreams and a million high-definition photos of the iceberg. In 1912, photography was a deliberate act. You had to set the exposure. You had to hold still. You had to hope the light was right. Because the last photo of Titanic is the final visual evidence of the ship in its "natural state," it represents the last moment of human innocence before the 20th century really began to get dark.

Father Browne: The man who almost stayed

We have to talk about Francis Browne because without him, our visual memory of the Titanic would be basically non-existent.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Browne was a photography enthusiast. He captured everything: the gymnasium, the reading rooms, passengers walking on the deck, and even the famous image of a young boy spinning a top. While he was on board, he became friendly with a wealthy American couple. They liked him so much they offered to pay his way all the way to New York.

Imagine that. A free ticket on the most luxurious ship in the world.

Browne telegraphed his superior for permission. The reply was short and blunt: "GET OFF THAT SHIP - PROVINCIAL."

That telegram saved his life.

When he stepped off at Queenstown, he took his rolls of film with him. After the sinking, newspapers went into a frenzy. They needed images. Browne’s photos became the most famous records of the voyage. However, even his photos aren't technically the last ones taken, as he was on the dock or the tender when the ship was still anchored. The very last photo of Titanic had to be taken from a distance as she cleared the harbor.

The disappearing horizon

The ship didn't just vanish into the night on April 14. It vanished into the distance on April 11.

The weather was clear. People watched from the hills of Cork. They watched until the four funnels—only three of which actually produced smoke—became tiny specks. There is something profoundly lonely about the last photo of Titanic. It captures the transition from a "place" (a ship full of people and warmth) to a "thing" (a silhouette on the water).

Historians like Don Lynch and Ken Marschall have spent decades analyzing these final frames. They look at the soot patterns. They look at the height of the water against the hull to estimate the weight of the coal. Every pixel of the last photo of Titanic has been scrutinized like a crime scene.

Misconceptions that drive historians crazy

You see it all the time on social media. Someone posts a photo of a sinking ship and calls it the "last photo."

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Usually, it's a photo of the Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship. Or it’s a shot from the 1997 movie. Or, most commonly, it’s a photo taken in Southampton days before the tragedy.

True experts differentiate between:

- The last photo taken on board (likely one of Father Browne’s deck shots).

- The last photo taken of the ship (the Morrogh photo or similar).

- The last photo of the crew (often confused with photos from the Carpathia).

The actual last photo of Titanic taken from the shore shows the ship as a dark shape against a gray sky. It isn't "pretty." It’s haunting. It’s the visual equivalent of a ghost story.

The technical reality of 1912 photography

Cameras back then weren't great for capturing moving objects at sea.

Most people were using "Brownie" cameras or folding pocket Kodaks. The film speeds were slow. This is why the last photo of Titanic looks a bit soft around the edges. If the ship was moving at even a few knots, the motion blur would start to kick in.

Also, the light in Ireland in April is... well, it's Irish. Overcast, diffused, and flat. This gave the final images a somber, muted tone that fits the narrative perfectly, even if it was just a byproduct of the weather.

I’ve looked at high-resolution scans of these final images. If you zoom in enough on some of the photos taken from the tenders, you can see tiny black dots on the deck. Those are people. They are individuals with names like Astor and Strauss and Goodwin. They are waving. They think they are on a holiday. They have no idea that in about 80 hours, the ship they are standing on will be two miles underwater.

Beyond the grain: What the photos don't show

The last photo of Titanic is silent.

It doesn't capture the sound of the massive reciprocating engines. It doesn't capture the smell of the fresh paint or the sea salt. It’s a vacuum.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

But it serves a vital purpose for the families of the victims. For decades after the sinking, these photos were the only way to "see" their loved ones' final environment. In a time before black boxes and satellite tracking, these snapshots were the last "pings" of a lost vessel.

Today, we have photos of the wreck. We have 8K footage of the rusted bow and the debris field. But those images are of a grave. The last photo of Titanic is an image of a living thing. That is why it holds more power than any photo of a rusted hull on the seafloor ever could.

Identifying the real deal

If you are looking for the authentic final images, look for the "Queenstown Series."

- The Anchored Shot: The ship is stationary. You can see the tenders alongside.

- The Turn: The ship begins to pivot to head out to sea.

- The Wake Shot: Taken from the back of the departing tender. You see the "Great Stern" of the ship.

- The Distant Profile: The ship is a long, dark line on the horizon.

The very last one—the one taken by John Morrogh—is the definitive "goodbye."

How to verify Titanic photography today

If you want to dive into this yourself, don't just trust a Google Image search. Most of those are mislabeled.

Go to the National Library of Ireland. They hold many of the original plates and prints. The Father Browne Collection is also a specific archive that has been digitized. When you look at these, look for the "Titanic" name on the lifeboats or the specific configuration of the A-deck promenade (which was different from the Olympic).

The Olympic had an open promenade. The Titanic had its forward half enclosed with glass screens. This is the easiest way to tell if you’re looking at a fake or a sister ship. If the windows aren't there, it’s not the Titanic.

Steps for the modern history enthusiast

If you’re interested in the visual history of the Titanic, there are a few things you should actually do to see the "real" story.

- Visit the Cobh Heritage Centre: This is located in the town where the last passengers boarded. Seeing the actual harbor where the last photo of Titanic was taken puts the scale into perspective. The hills look exactly the same today as they did in the photos.

- Study the Father Browne Archive: Buy the book Father Browne's Titanic Album. It’s the best way to see the photos in their original context without the "internet mystery" fluff.

- Cross-reference with the Deck Plans: When you look at a photo of the ship, have a copy of the deck plans open. Try to identify which window belongs to which cabin. It turns the ship from a legend back into a building where people lived.

- Check the Weather Records: On April 11, 1912, the conditions were "fair with light winds." If you see a "last photo" with massive crashing waves, it’s a fake or a different ship.

The last photo of Titanic remains a bridge between two worlds. It’s the last piece of evidence from a world that believed it had finally conquered nature. We keep looking at it because we’re still looking for the moment things went wrong. But in that photo, everything is still right. The ship is moving. The smoke is rising. The horizon is waiting.