You’ve probably seen the tropes a thousand times. The clanging bars. The shadow of the gallows. The desperate man pacing a cell while the clock ticks toward midnight. Most of those cliches actually started somewhere real, and if you trace the DNA of the modern prison thriller back to its most jagged roots, you’ll find The Last Mile 1959 film. It isn't just another b-movie from the fifties. It is a claustrophobic, sweat-soaked pressure cooker that fundamentally changed how we look at "Death Row" on screen.

Honestly, it's a bit of a shocker for people used to seeing Mickey Rooney as the energetic song-and-dance man or the wholesome Andy Hardy. In this flick, he’s "Killer" John Mears. He’s small, he’s trapped, and he is absolutely terrifying.

Directed by Howard W. Koch, this remake of the 1932 classic (which originally starred Preston Foster) took a stage-play approach that makes the viewer feel like the walls are closing in. It’s tight. It’s mean. It doesn't apologize for being ugly.

The Brutal Setup of the 1959 Remake

The story doesn't waste your time. We are dropped straight into the "death house" of a state penitentiary. Seven cells. Seven men. All of them are waiting for their turn in the electric chair. The atmosphere is thick with the smell of floor wax and impending doom. While the 1932 version was groundbreaking for its time, The Last Mile 1959 film leaned into the psychological disintegration of men who have nothing left to lose.

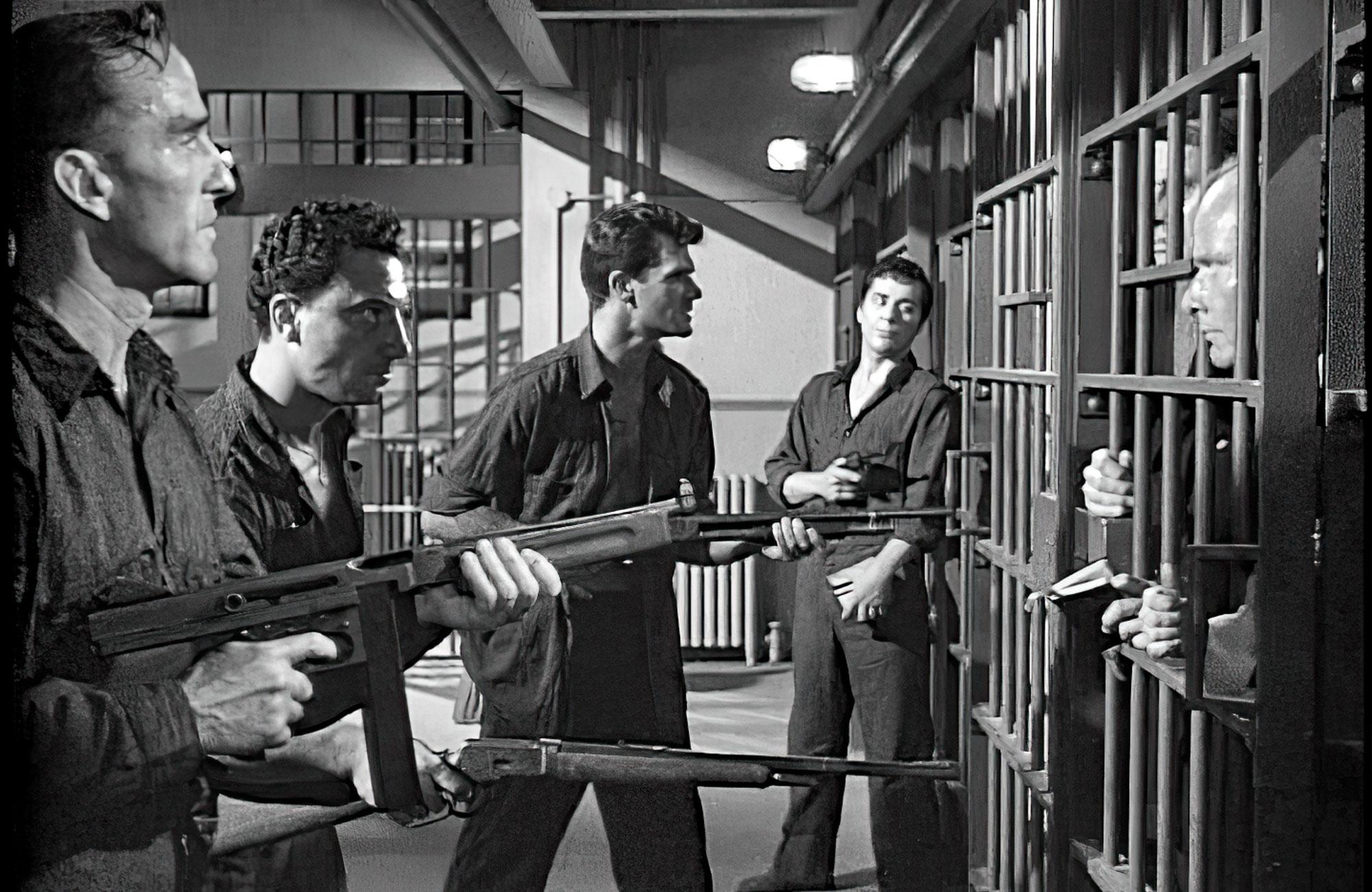

Mickey Rooney’s performance is the engine here. He’s not playing a hero. Mears is a career criminal with a hair-trigger temper who orchestrates a desperate, doomed breakout. He manages to overpower a guard, seize the keys, and suddenly the hunters become the hunted. But where are they going to go? They’re still stuck in a fortress. That irony is what gives the film its bite.

You’ve got a supporting cast that fills out the desperation perfectly. Frank Conroy plays the warden with a sort of weary, bureaucratic detachment that makes the cruelty feel even more institutional. Then there’s Clifford David as Richard Walters, the man Mears is trying to save—or perhaps just use as a catalyst for his own rage. The movie basically asks: what does a man become when the state has already decided he's dead?

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

Why the Stage-to-Screen Translation Works

Most films adapted from plays feel "static." You can tell the actors are waiting for their cues on a wooden floor. But Koch used the camera in The Last Mile 1959 film to weaponize that stillness.

- The lighting is high-contrast noir.

- Shadows stretch across the cell blocks like fingers.

- Close-ups are uncomfortably tight, showing every bead of sweat on Rooney's forehead.

It feels like a documentary of a nightmare. There’s a specific rhythm to the dialogue that feels less like a script and more like a series of barks. Short. Sharp. Violent.

The film was shot on a relatively low budget, but that actually helps. The grit feels authentic. It doesn't have the glossy sheen of a big MGM production. It feels like it was filmed in a basement, which, for a story about men buried alive in the legal system, is exactly the right vibe.

Mickey Rooney’s Career Pivot

Let’s talk about Mickey. By 1959, his "golden boy" years were in the rearview mirror. He needed to prove he could do more than just be charming. In The Last Mile 1959 film, he leans into his physicality. Because he’s a shorter guy, his aggression feels concentrated. He stalks the corridors of the cell block like a caged animal.

It’s a masterclass in "small man syndrome" utilized for dramatic effect. When he holds a gun, you believe he’ll use it. Not because he’s a movie star, but because he looks like a man who has been stepped on one too many times. Critics at the time were polarized, but looking back now, it's clearly one of his most brave performances. He threw away the mask of the entertainer and showed us something jagged.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

The Social Commentary Most People Miss

While it functions as a thriller, the movie is a stinging indictment of capital punishment. It doesn't preach. It doesn't give you a long-winded speech about the sanctity of life. It just shows you the machinery of death.

The "Last Mile" refers to the walk from the cell to the chair. By focusing so heavily on the ritual—the last meal, the shaving of the head, the testing of the equipment—the film forces the audience to participate in the execution. It’s uncomfortable. It’s supposed to be.

In the late fifties, the US was starting to have serious internal debates about the death penalty. This film poured gasoline on that fire. It showed that the men behind the bars weren't just monsters; they were terrified, flawed, and often broken human beings. Even "Killer" Mears has a moment of vulnerability that makes you question the morality of the system, even if you don't like the man.

Technical Details and Trivia

The film was produced by Milton Katselas and distributed by United Artists. Interestingly, the screenplay by Milton Subotsky stayed very close to the original 1929 play by John Wexley. Wexley himself was known for his social activism, and that DNA is visible in every scene.

- Cinematography: Joseph Brun brought a stark, realist style that avoided the "pretty" lighting of the era.

- Running Time: A lean 81 minutes. No filler.

- Release Date: January 1959.

It’s also worth noting that this wasn't the first time the story had been told, but it arguably remains the most visceral. The 1932 version had the benefit of being "Pre-Code," meaning it could be more violent than films in the late 30s or 40s. However, by 1959, the Production Code was weakening. This allowed the filmmakers to depict the riot with a level of intensity that earlier versions simply couldn't touch.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

Impact on the Prison Genre

Without The Last Mile 1959 film, we don't get the same DNA in movies like Cool Hand Luke or The Shawshank Redemption. It established the "Death Row" sub-genre as a place for character study rather than just action.

The trope of the "ticking clock" execution? This movie perfected it. The dynamic between the "good" prisoner and the "hardened" leader? That’s Mears and Walters. Even the way sound is used—the echoing footsteps, the buzzing of the electric chair—set a standard that sound designers still use today to create tension.

How to Watch it Today

Finding a pristine copy can be tricky. It isn't always sitting on the front page of Netflix. However, it frequently pops up on Turner Classic Movies (TCM) or specialized noir streaming services. If you’re a fan of physical media, there have been various DVD releases, though a high-definition Blu-ray restoration is something film historians are still clamoring for.

Watching it now, you have to look past some of the 1950s "tough guy" slang. It’s a product of its time. But the core emotion—the raw, naked fear of a man facing his end—is timeless.

Actionable Insights for Film Buffs

If you’re planning to dive into this classic, here is how to get the most out of the experience:

- Watch the 1932 version first: If you can find it, seeing the Preston Foster version provides a fascinating look at how cinematic language evolved in 27 years. The 1959 version is much more focused on the interior psyche of the characters.

- Pay attention to the soundscape: Turn up the volume. The silence in this movie is just as important as the dialogue. The ambient noise of the prison creates a sense of dread that many modern films fail to replicate with loud scores.

- Research the John Wexley play: Understanding that this was originally written for the stage explains the tight blocking and the heavy reliance on dialogue to build tension.

- Compare with "I Want to Live!" (1958): Released just a year prior, this is another powerhouse capital punishment film. Watching them back-to-back gives you a perfect snapshot of the American mindset regarding the legal system at the end of the 1950s.

The best way to appreciate The Last Mile 1959 film is to treat it as a piece of "Chamber Cinema." Forget the world outside the prison walls. Focus on the seven cells. By the time the credits roll, you'll understand why this little black-and-white film still haunts the people who see it. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most terrifying monsters aren't the men in the cells, but the cold, mechanical certainty of the walk down the hall.

Go find a copy. Dim the lights. Experience the tension for yourself.