Snow. Pure, unblemished, white snow. That’s how it ended.

Honestly, it’s rare to see a creator quit while they’re ahead. Most of the time, we watch our favorite things slowly decay into parodies of themselves. Think about those sitcoms that go on for twelve seasons until the main cast is replaced by cousins nobody likes. Or the comic strips that have been running on autopilot for forty years, recycling the same three jokes about Mondays or lasagna. Bill Watterson didn’t do that. On December 31, 1995, he just... stopped. The last comic of Calvin and Hobbes wasn't a tearful goodbye or a "where are they now" montage. It was a beginning.

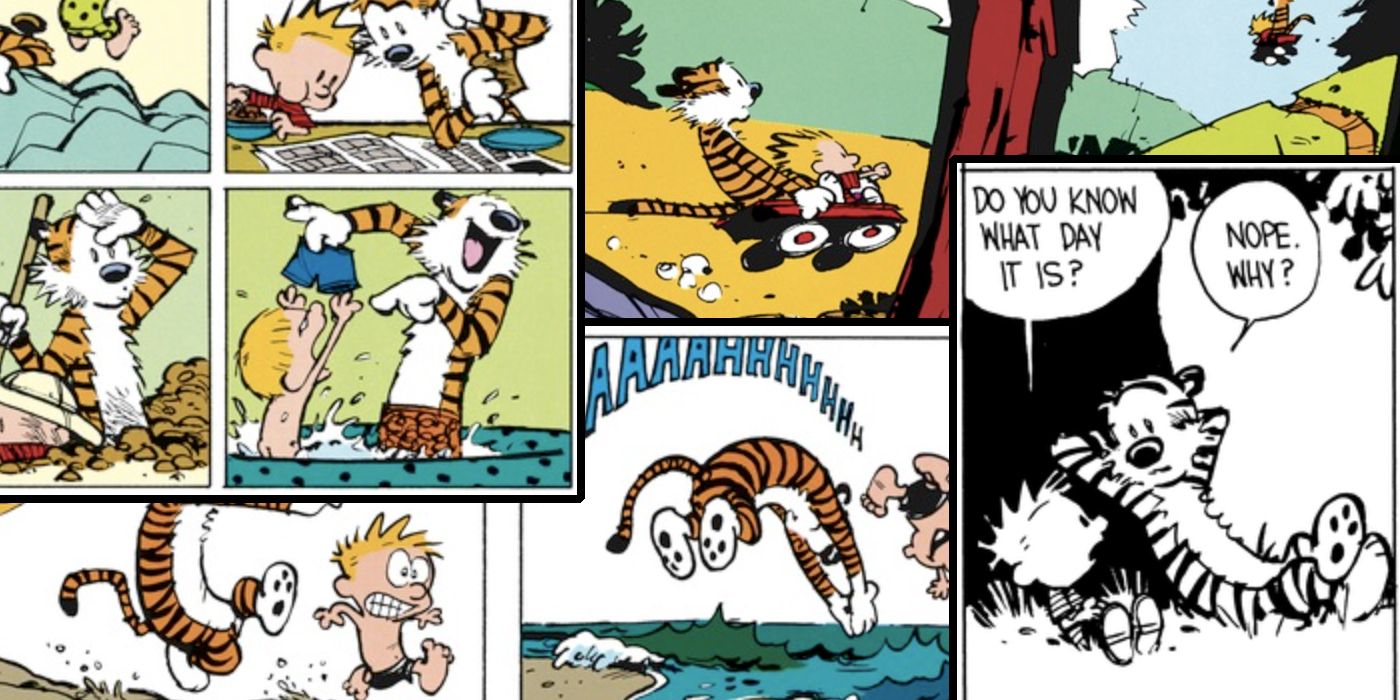

People still talk about it. Why? Because the final Sunday strip captured the entire ethos of the series in just a few panels. A boy, his tiger, a fresh snowfall, and a sled. It felt like a punch to the gut and a warm hug at the same time. Watterson spent a decade fighting syndicates, refusing to sell plush dolls, and demanding more space for his art. Then, at the height of his powers, he left the table.

The Day the Magic Ended (Or Didn't)

The final strip is a masterpiece of minimalism. It starts with Calvin and Hobbes stepping outside into a world transformed by a blizzard. Everything is white. The detail is sparse but intentional. Calvin remarks on how the world looks like a "fresh sheet of paper," which is a pretty clear nod to Watterson's own creative process.

They climb a hill. They sit on their sled. The final line of dialogue in the history of the strip is Calvin saying, "Let's go exploring!" They zoom off into the white void.

It’s perfect.

It’s also incredibly frustrating if you’re the kind of person who wants closure. There was no wedding, no graduation, no reveal that Hobbes was "real" or "fake"—because that wasn't the point. Watterson understood something that many modern writers forget: the journey is the destination. By leaving the story open, he ensured that Calvin and Hobbes would stay six years old forever. They never had to grow up and get boring jobs. They’re still out there in the woods somewhere, probably arguing about the rules of Calvinball.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Why Watterson Really Quit

You’ve probably heard the rumors. People used to say he was a recluse or that he hated his fans. Neither is true. Bill Watterson just hated the "business" of art. He famously fought a long, bloody battle with Universal Press Syndicate over merchandising. He didn't want a "Calvin and Hobbes" cartoon. He didn't want theme parks. He definitely didn't want those bootleg stickers of Calvin peeing on truck logos—which, by the way, he never saw a dime from and absolutely despised.

By the time the last comic of Calvin and Hobbes rolled around, Watterson was tired. He had already taken two sabbaticals. In his 1990 speech at Kenyon College, he talked about the pressure of producing a daily strip. It’s a grind. You have to be funny every single day, forever. He felt he had said everything he wanted to say with these characters. He didn't want to become a "zombie" strip.

"This is a department of self-interest," Watterson once wrote regarding his refusal to merchandise. "I worked too hard to let this be turned into a product."

When he sent the letter to newspaper editors in 1995 announcing his retirement, the world went into a sort of collective mourning. Over 2,400 newspapers carried the strip at its peak. Imagine that today. We don't have that kind of monoculture anymore. Everyone was reading the same six panels every morning over coffee. When it vanished, it left a massive, tiger-shaped hole in the morning routine of millions.

The Technical Brilliance of the Final Year

If you look back at the strips leading up to the end, Watterson was experimenting like a madman. He had successfully fought for a "no-cut" Sunday layout. Back then, newspapers would often chop off the top row of a comic to save space. Watterson hated this because it ruined the pacing and the art. He eventually told the syndicates that if they wanted his strip, they had to print it exactly as he drew it—full page or nothing.

This led to some of the most beautiful art ever seen in a funny-paper. He was using watercolors, intricate line work, and cinematic perspectives. He was pushing the medium of the "comic strip" into the realm of "fine art." The last comic of Calvin and Hobbes reflected this shift toward simplicity and space. He wasn't trying to cram in a punchline. He was trying to evoke a feeling.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Common Misconceptions About the Ending

Wait, let's clear some stuff up. There are a few "fake" endings floating around the internet that people mistake for the real thing.

- The "Ritalin" Comic: There’s a fan-made strip where Calvin takes medication and Hobbes turns into a normal stuffed animal. It’s depressing and completely goes against the spirit of the original work. Watterson didn't write it.

- The "Grown Up" Calvin: There are several strips showing Calvin as a dad with his own daughter, Bacon. These are often well-drawn and sweet, but again, they are fan art.

- The "Hobbes is a Hallucination" Theory: People love to debate whether Hobbes is "real." Watterson’s own take was more nuanced. He didn't see Hobbes as a puppet or a hallucination. He saw it as two different versions of reality co-existing. The final strip honors this by showing them together, as equals, in their shared world.

The Cultural Impact of the Sled

That sled is a recurring motif throughout the entire series. It’s a vehicle for their philosophical debates. Usually, they’re hurtling down a mountain toward a cliff while Calvin explains his nihilistic worldview or his latest scheme to get out of doing homework.

Choosing the sled for the last comic of Calvin and Hobbes was a deliberate call-back. It represented the speed of life, the lack of control we have over our trajectory, and the sheer joy of the ride. When they disappear into the snow, they aren't dying or ending; they’re just moving out of our sight.

It’s been decades since that strip was published. In that time, we’ve seen the rise of social media, the death of many print newspapers, and a total shift in how we consume media. Yet, "Calvin and Hobbes" remains one of the best-selling graphic novel collections every single year. Parents give the books to their kids. Kids grow up and find new meanings in the jokes. It’s timeless because it’s about the interior life of a child, and that doesn't change regardless of whether the year is 1985 or 2026.

The Legacy of the "Last" Word

Watterson didn't do interviews for years after he finished. He moved back to Ohio. He took up painting. He lived a quiet life. He didn't try to "reboot" the franchise. He didn't sell the movie rights to Disney for a billion dollars.

That integrity is why the strip still feels "pure." When you read the last comic of Calvin and Hobbes, you aren't seeing a brand being retired. You're seeing an artist finish a thought. There’s a specific kind of dignity in knowing when to walk away.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Actionable Ways to Revisit the Magic

If you’re feeling nostalgic or if you’ve never actually read the full run, here is how to actually engage with the work today without falling for the "best of" fluff:

- Get The Complete Calvin and Hobbes: It’s a massive three or four-volume set. It’s heavy enough to break a toe, but it contains every single strip in chronological order. Reading them in order lets you see Watterson’s art evolve from standard "big-foot" cartooning to the fluid, gorgeous style of the later years.

- Study the Sunday Strips: Look specifically at the strips from 1992 to 1995. This is when Watterson had his artistic freedom. The layouts are insane. One strip might be a single giant panel of a dinosaur, while the next is twenty tiny panels of a conversation.

- Watch the Documentary "Dear Mr. Watterson": It doesn't feature the man himself (obviously), but it explores the impact the strip had on other cartoonists and why the refusal to merchandise was such a revolutionary act.

- Look for the 2014 "Secret" Strips: Believe it or not, Watterson did return to the funny pages for three days in 2014. He secretly guest-illustrated the strip "Pearls Before Swine" by Stephan Pastis. The proceeds went to charity. It was the first time we saw his pen work in a newspaper in nearly twenty years, and it was glorious.

The last comic of Calvin and Hobbes reminds us that the world is big, full of possibility, and ours to explore. It’s a pretty good lesson to keep in mind, even if you don't have a talking tiger to help you navigate the snow.

Go find a copy of that final Sunday strip. Look at the white space. Think about what you’d put on your own "fresh sheet of paper" today. That’s the real legacy Bill Watterson left behind—not just a story about a kid, but a reminder to keep looking for the magic in the mundane.

Next Steps for the Fan:

To truly appreciate the depth of Watterson's work, compare the first week of strips from November 1985 to the final month in December 1995. You’ll see a staggering transformation in both the philosophy of the characters and the confidence of the ink lines. For the most authentic experience, avoid digital scans and try to find the printed "Treasury" books like The Indispensable Calvin and Hobbes or The Days are Just Packed, which preserve the original coloring and scale Watterson intended for his readers.