He looked tired.

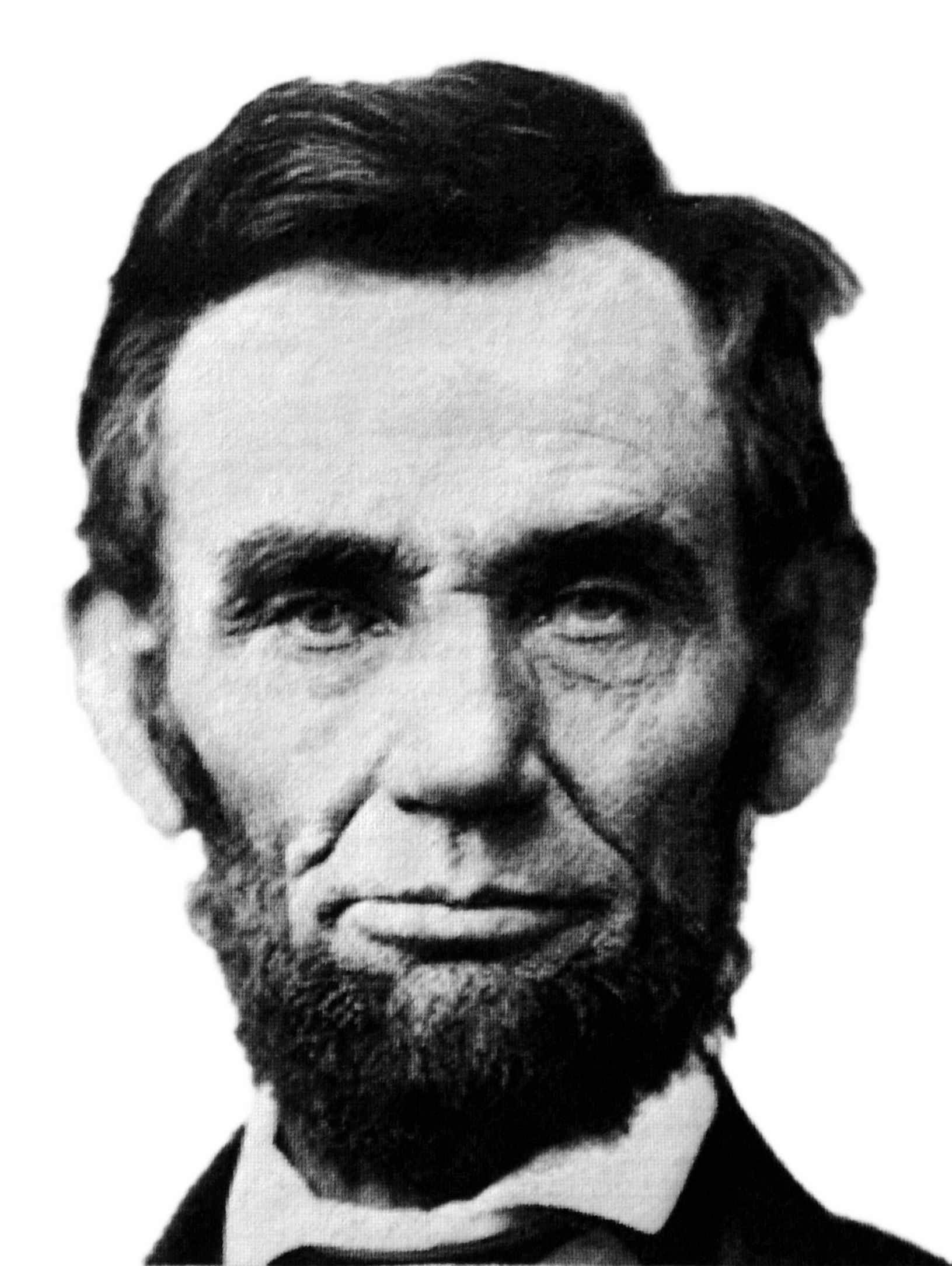

Honestly, looking at the images from early 1865, "tired" feels like a massive understatement. Abraham Lincoln had spent four years watching his country tear itself apart, and it showed in every line carved into his face. People often obsess over the last Abraham Lincoln photo because they want to see the toll of the Civil War captured in a single frame. They want to see the man who saved the Union right before the theater curtains closed on him for good. But here’s the thing: historians still bicker about which photo actually holds the title of "the last."

It isn't just a matter of checking a date on a receipt. Photography in the 1860s was a messy, chemical-heavy process, and record-keeping wasn't always the priority when the President of the United States walked into your studio.

The Gardner Portrait: The "Cracked Plate" Mystery

Most folks point to the Alexander Gardner session on February 5, 1865. This is the big one. It’s the session that produced the famous "cracked plate" portrait. You’ve probably seen it. Lincoln has this ghostly, slight smile—rare for him—and a jagged crack runs right through the top of his head across the glass negative.

Gardner actually thought the negative was a total loss. He pulled one print and then threw the plate away. That single print is now a priceless artifact in the National Portrait Gallery. For a long time, the world basically accepted this as the final sitting. It makes for a poetic story, doesn't it? The glass breaking right before the man himself was broken by an assassin’s bullet.

But history is rarely that clean.

Some experts, like the late Harold Holzer or the researchers at the Lincoln Presidential Library, have spent decades squinting at the shadows and the length of Lincoln's beard to figure out if there was something later. We know Lincoln was busy. Between February and April 1865, he wasn't exactly lounging around waiting for a camera. He was at City Point visiting Grant. He was walking through the ruins of Richmond. He was trying to figure out how to put a broken nation back together without hanging every soul in the South.

The Henry F. Warren Mystery: Was April 1865 the Real Date?

This is where the waters get muddy. A photographer named Henry F. Warren came to the White House on March 6, 1865. This was just two days after Lincoln’s second inauguration. Warren didn't have a fancy studio setup; he basically set up on the balcony.

📖 Related: False eyelashes before and after: Why your DIY sets never look like the professional photos

The resulting image is... well, it’s rough. Lincoln looks exhausted. He’s sitting outside, the lighting is harsh, and he looks older than 56. For years, some collectors claimed this was the last Abraham Lincoln photo taken from life. They argued that because it happened after the inauguration, it superseded the Gardner portraits.

But then you have the "secret" photos.

There is a long-standing rumor—and some evidence—of a photo taken by a man named Thomas Walker on the White House portico just weeks before the assassination. The problem? The provenance is shaky. In the world of Lincoln scholars, "shaky" is a death sentence for a claim. You need the receipt. You need the diary entry. Without those, a photo is just a mystery in a copper frame.

Why We Are Obsessed With His Face

Lincoln was the first "photographic" president in the sense that the public could actually track his aging in real-time. When he arrived in Washington in 1861, he was a relatively smooth-faced (though always rugged) man. By the time the shutter clicked for the last Abraham Lincoln photo, he looked like he’d aged twenty years in four.

His face became a map of the war.

Think about the technical limitations of the time. You had to sit still. For a long time. If you moved, you blurred. So when we look at these final images, we are looking at Lincoln in a moment of forced stillness. He wasn't posing for a "cool" shot. He was holding his breath.

There's a specific detail in the Gardner photos that people often miss. If you look at his hands in the seated versions of those February shots, he’s holding his spectacles and a pencil. It feels intimate. Like we walked in on him while he was drafting the Second Inaugural Address. It’s that intimacy that drives the search for the "final" image. We want to be as close to the moment of his death as possible to see if he knew. (Spoilers: He didn't, though his dreams lately had been pretty dark).

👉 See also: Exactly What Month is Ramadan 2025 and Why the Dates Shift

The Post-Mortem Photo: The One We Weren't Supposed to See

If we are being literal about the "last" photo, we have to talk about the one taken in New York.

On April 24, 1865, Lincoln’s body was lying in state at City Hall in New York. A photographer named Jeremiah Gurney Jr. set up his camera and took a picture of the President in his coffin. It’s a haunting, high-angle shot.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton was absolutely furious when he found out. Stanton was a man who lived for control and order. He saw the photo as a violation of the President’s dignity. He ordered all the negatives and prints destroyed immediately. He wanted it gone from history.

But one print survived.

It was tucked away in the papers of John Hay, Lincoln's secretary, and didn't resurface until 1952. While technically the "last" image of Abraham Lincoln, most historians categorize it separately from the "life" portraits. It’s a different beast entirely. It’s a crime scene photo and a funeral memento rolled into one. It doesn't show the man; it shows the shell.

How to Spot a "Fake" Lincoln Photo

Every few years, someone claims to have found a new "last" photo in an attic or a shoebox at a garage sale. Usually, it's just a guy with a beard.

If you're ever looking at a supposed "new" Lincoln discovery, check these three things that the pros use:

✨ Don't miss: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

- The Ear: Lincoln’s left ear had a very distinct shape. It’s like a fingerprint.

- The Mole: He had a prominent mole on his right cheek, just above the corner of his mouth. In many "found" photos, the mole is missing or on the wrong side (though you have to account for mirrored images in old daguerreotypes).

- The Hair: By 1865, Lincoln’s hair was a chaotic mess, and his beard was trimmed shorter than it had been in 1862.

Most of the "lost" photos turn out to be lithographs or later recreations using actors. During the late 19th century, people were so hungry for Lincoln memorabilia that they would literally create it out of thin air.

The Reality of the Final Sitting

Whether the Gardner crack-plate is the final one or the Warren balcony shot takes the prize, the impact remains the same. The last Abraham Lincoln photo serves as a silent witness to the end of an era.

Lincoln hated sitting for portraits. He called it "the ordeal." He found the whole process of staying still for a camera to be tedious and annoying. There is something deeply ironic about the fact that a man who hated being photographed has become the most photographed human being of the 19th century.

Maybe he’d be annoyed that we’re still staring at his wrinkles 160 years later. Or maybe he’d understand. We’re just trying to find the man behind the myth, and the closer we get to the end of his life, the more human he seems to become.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into the visual history of the 16th President, don't just look at digital scans. Digital ruins the texture.

- Visit the National Portrait Gallery: If you are ever in D.C., go see the Gardner "cracked plate" in person. The scale of it changes how you feel about the damage to the glass.

- Study the Meserve Collection: Frederick Hill Meserve was the guy who basically organized Lincoln’s photos into a numbering system (the "M" numbers). It’s the gold standard for verifying if a photo is legit.

- Check the Beard: If you see a photo of "Lincoln" with a huge, bushy beard and people claim it's from 1865, they’re wrong. His beard was notably groomed and shorter in his final months.

- Read "Lincoln in Photographs": This book by Charles Hamilton and Lloyd Ostendorf is the "bible" for this topic. It’s out of print but easy to find used, and it breaks down every single known sitting with forensic detail.

Ultimately, the search for the "last" photo is about our own desire for closure. We want to see the final frame of the movie. Even if the exact date of the very last click of the shutter remains a point of debate among academics, the images we do have provide a hauntingly clear view of a man who gave everything he had to a cause he didn't live to see fully realized.