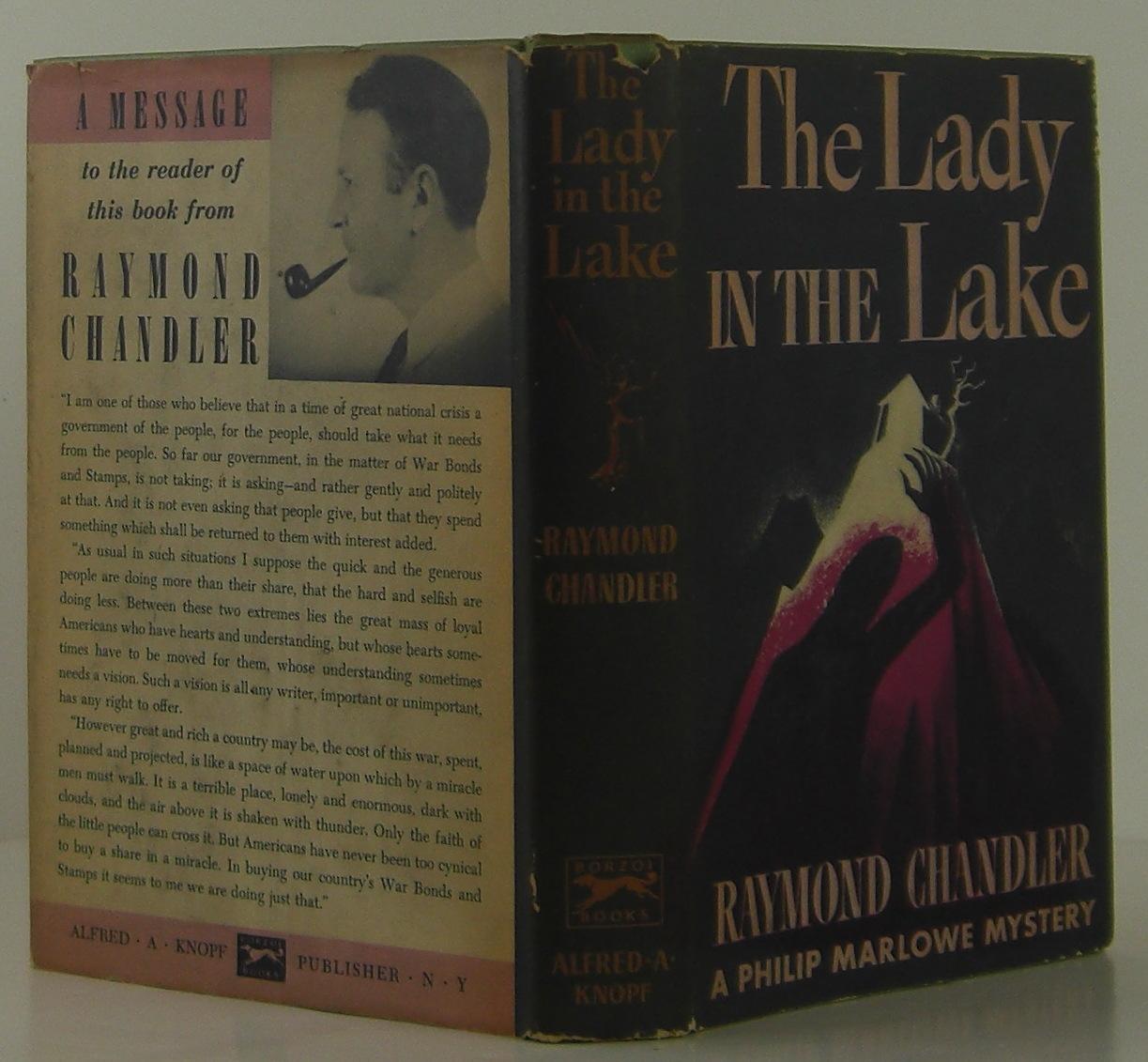

Raymond Chandler was a man who hated "whodunits." He thought they were bloodless. To him, the typical British mystery was a collection of cardboard cutouts playing a game of Clue in a drawing room. He wanted the streets to smell like real fear. In 1943, he gave us The Lady in the Lake, and honestly, it changed everything for the Philip Marlowe series. It’s the book where the hardboiled detective finally leaves the neon-soaked smog of Los Angeles for the deceptive "purity" of the mountains.

You've probably seen the tropes. A missing wife. A wealthy husband who seems too calm. A body that’s been in the water so long it’s basically unrecognizable. But The Lady in the Lake Raymond Chandler wrote isn't just a pulp thriller. It’s a masterclass in how to lie with the truth.

The Real Murder That Inspired the Book

Most people think Chandler just sat in his Pacific Palisades home and made this stuff up. Not quite. He was a sponge for the local news. The plot of the novel was actually a "cannibalized" version of his own earlier short stories—Bay City Blues and The Lady in the Lake (the short version)—but those stories were rooted in real-life tragedies.

One big influence was the 1935 death of Doris Dazey. Her husband was a prominent Santa Monica doctor, and she was found dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. The case was a mess. It was ruled a suicide, then a grand jury got involved years later because her parents wouldn't let it go. Chandler saw how a "respectable" community could swallow a murder whole to keep things quiet. He took that vibe and moved it to the fictional "Little Fawn Lake."

Then there was the Thelma Todd case. She was a famous actress found dead in a garage, also from carbon monoxide. Chandler noticed a weird detail: one of her shoes was scuffed, and one wasn't. In the book, he uses these tiny, physical inconsistencies to tip Marlowe off that things aren't what they seem.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Why the Plot is So Hard to Forget

The setup is classic Marlowe. Derace Kingsley, a rich businessman, hires Marlowe to find his wife, Crystal. She supposedly ran off to Mexico to marry a gigolo named Chris Lavery. But when Marlowe goes up to the Kingsley cabin in the San Bernardino Mountains, he finds something else. A body.

The Identity Trap

This is where Chandler gets brilliant. The "lady in the lake" is found by Marlowe and a caretaker named Bill Chess. She’s been underwater for a month. Her face is gone. Bill Chess identifies her as his own wife, Muriel, who left him around the same time Crystal disappeared.

But wait.

In this world, identity is a mask. Chandler leans heavily into the idea that "small blondes" are basically interchangeable in the eyes of the law and men. It’s a cynical take. He writes about how a change of clothes or lighting makes these women look identical. This isn't just a plot device; it’s a commentary on how the men in the book don't really see the women at all.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The Twist You Won't See Coming

Honestly, the ending is a bit of a brain-melter if you aren't paying attention. It turns out the woman in the lake wasn't Muriel Chess. It was Crystal Kingsley. And the woman pretending to be Crystal Kingsley was actually Mildred Haviland—a former nurse with a body count that would make a hitman blush.

Mildred is the ultimate "femme fatale," but she’s more than just a trope. She’s a survivor. She killed Dr. Almore’s wife years ago, killed Crystal Kingsley to steal her identity, and killed her lover Lavery when he became a liability. She’s the engine of the whole book.

That Weird Point-of-View Movie

We have to talk about the 1947 film adaptation. It’s one of the strangest experiments in Hollywood history. Robert Montgomery directed it and played Marlowe, but he decided to film the entire thing in the first person.

You only see Marlowe when he walks past a mirror.

🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Basically, the camera is Philip Marlowe. The other actors stare directly into the lens and talk to you. It was supposed to be "revolutionary," but it kind of failed. Why? Because Chandler’s prose is about observation, not just looking. When you read the book, you're in Marlowe's head, feeling his cynicism. In the movie, you're just a floating camera. It’s a bit jarring, especially when someone tries to punch the "camera."

Why It Still Matters Today

The Lady in the Lake Raymond Chandler wrote is unique because it’s a "war novel" without being about the war. It was written right after Pearl Harbor. You see it in the background—the gas rationing, the tension, the feeling that the world is falling apart and nobody is coming to save it.

Marlowe is the "shop-soiled" knight. He isn't perfect. He’s often lonely. But in a book filled with people changing their names and murdering their spouses, he’s the only one who stays the same.

If you want to dive deeper into this world, here is what you should do next:

- Read the book before watching the movie. The prose is the real star here. Look for the way Chandler describes the heat of the desert versus the "cold, still" water of the lake.

- Track the "Muriel/Mildred" timeline. On your first read, it's easy to get lost. Try to note when Mildred changes her identity—it makes the final reveal much more satisfying.

- Compare it to The Big Sleep. Notice how Marlowe is more weary in this one. He's older. The world is grimmer.

- Check out the real-life Dazey case. Looking up the 1930s news clippings about Dr. George Dazey gives you a haunting look at the "Bay City" corruption Chandler was actually mocking.

The book isn't just a mystery; it’s a ghost story about the women who disappear in the shadows of powerful men. It’s as relevant now as it was in 1943.