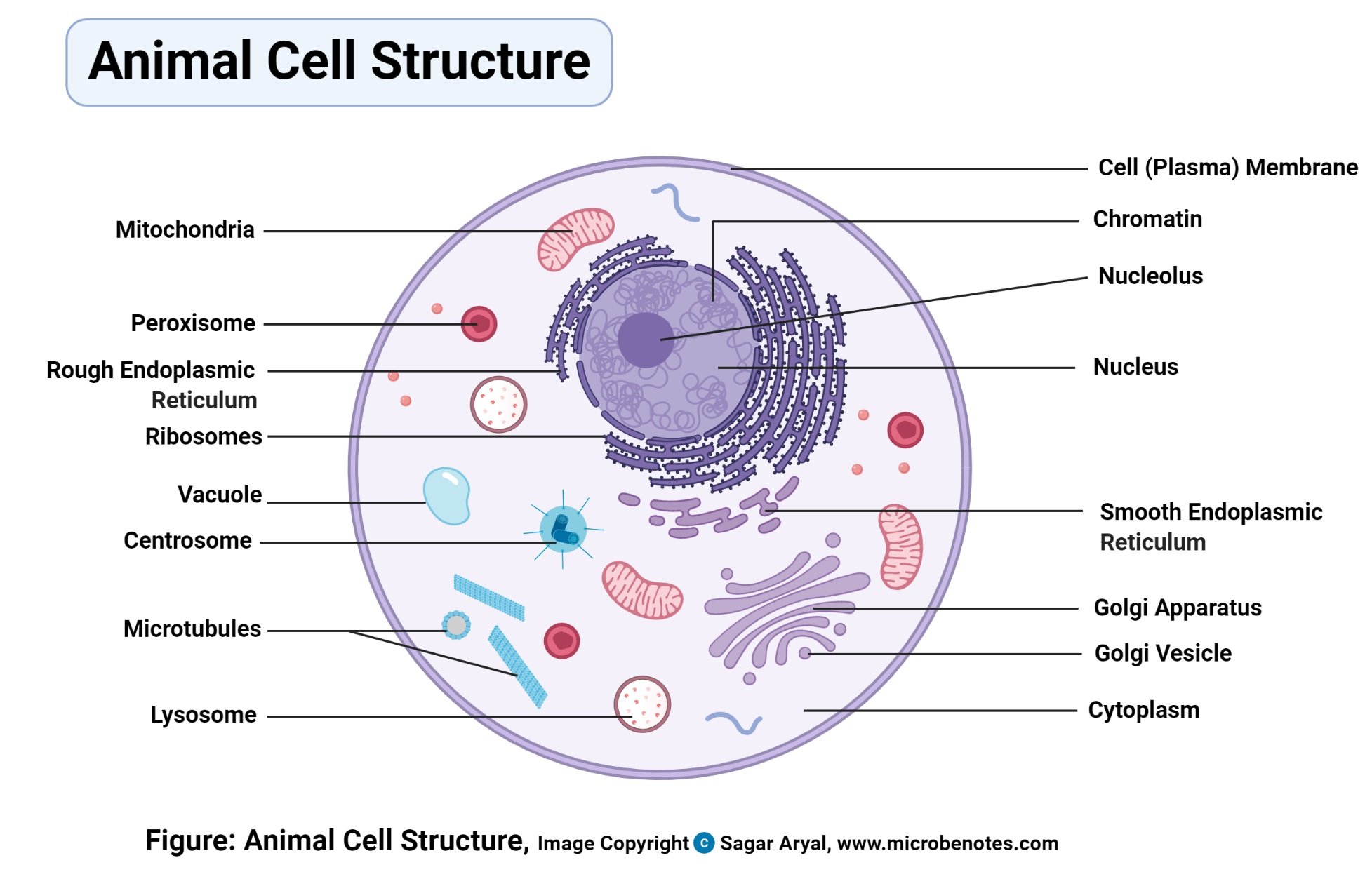

You probably remember that squishy-looking blob from middle school biology. The one with the "powerhouse" bean and the big empty bubble in the middle. It’s the labeled diagram of animal and plant cell, a staple of every science classroom since forever. But honestly? Most of those diagrams are kinda lying to you. They make cells look like static, organized little plastic toys when the reality is a chaotic, crowded soup of molecular machinery that never stops moving.

If you’re looking at a labeled diagram of animal and plant cell, you’re basically looking at a blueprint for life itself. Whether it’s the skin on your hand or the leaf on an oak tree, these tiny units are doing the heavy lifting. But they aren't identical. Not even close. Understanding where they diverge is how we understand why a sunflower can stand tall without a skeleton while you definitely can't.

Why the Wall Matters More Than You Think

The first thing you'll notice on any decent labeled diagram of animal and plant cell is the border. Plant cells are boxy. They have this rigid, thick outer layer called the cell wall. It’s made of cellulose—basically the same stuff in your favorite cotton t-shirt. This wall is the reason trees can grow hundreds of feet into the air without collapsing into a pile of mush.

Animal cells? They're soft. They only have a cell membrane. This lipid bilayer is flexible, allowing your cells to move, squish, and form complex shapes like neurons or muscle fibers. Imagine trying to do yoga if every cell in your body was encased in a wooden box. It wouldn't work. The cell membrane is like a picky bouncer at a club; it decides exactly who—meaning ions and molecules—gets in and who stays out on the sidewalk.

The Green Machines

Look at the plant side of your diagram. See those green ovals? Those are chloroplasts. This is where the magic—or rather, photosynthesis—happens. Inside these organelles, chlorophyll captures sunlight to turn water and carbon dioxide into glucose. It’s literally solar power. Animal cells don't have these because we eat our energy instead of making it from the sun. If we had chloroplasts, we’d probably just hang out in parking lots all day "recharging" instead of going to lunch.

✨ Don't miss: What Cloaking Actually Is and Why Google Still Hates It

The Powerhouse and the Trash Can

We have to talk about the mitochondria. Everyone knows the meme, but few people realize how weird they actually are. They have their own DNA. Scientists like Lynn Margulis championed the endosymbiotic theory, which basically says mitochondria were once independent bacteria that got "swallowed" by a bigger cell and decided to stay. In a labeled diagram of animal and plant cell, you'll see mitochondria in both. Plants need them too! Even though they make their own food, they still need to break it down into ATP (adenosine triphosphate) to use it.

The Central Vacuole vs. Lysosomes

In the plant cell, there’s usually a giant "empty" space. That’s the central vacuole. It’s not actually empty; it’s filled with water and nutrients. When a plant is well-watered, this vacuole pushes against the cell wall, creating turgor pressure. That's why a watered plant stands up and a thirsty one wilts.

Animal cells have vacuoles too, but they’re tiny and temporary. Instead, animals rely heavily on lysosomes. These are the "suicide bags" or recycling centers. They contain digestive enzymes that break down waste. While some plant cells have lysosome-like structures, the heavy lifting of waste management in plants is often handled by that giant central vacuole.

The Control Center: Nucleus and Beyond

The nucleus is the brain, sure. It holds the DNA. But have you ever looked closely at the stuff surrounding it? The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) looks like a stack of pancakes. The "rough" ER is covered in ribosomes, which are the actual protein factories. The "smooth" ER handles lipids and detoxification.

🔗 Read more: The H.L. Hunley Civil War Submarine: What Really Happened to the Crew

Then there’s the Golgi apparatus. Think of it as the FedEx of the cell. It takes the proteins made by the ER, packages them into little bubbles called vesicles, and tags them with a "shipping address" so they go to the right part of the body. Without the Golgi, your cells would just be full of loose parts with nowhere to go.

Centrioles and the Cytoskeleton

Here is a nuance most people miss: centrioles. On a labeled diagram of animal and plant cell, you’ll usually only find centrioles on the animal side. They look like little bundles of pasta. These are crucial for cell division (mitosis), helping to pull chromosomes apart. Most "higher" plants have found other ways to divide without them, proving there’s more than one way to split a cell.

The cytoskeleton is the unsung hero. It’s a network of protein fibers—microtubules and microfilaments—that gives the cell its internal structure. In an animal cell, it’s the only thing keeping the whole thing from being a puddle. It also acts as a highway system for transport vesicles.

Real-World Nuance: It’s Not Always This Simple

The diagrams in textbooks are "typical" cells. But nature loves an exception. Take human red blood cells—they actually spit out their nucleus to make more room for oxygen. Or look at Caulerpa taxifolia, a type of seaweed that is one giant cell with thousands of nuclei.

💡 You might also like: The Facebook User Privacy Settlement Official Site: What’s Actually Happening with Your Payout

When you study a labeled diagram of animal and plant cell, remember it’s a generalized map. Real life is messier. Fungal cells, for example, have cell walls like plants but use chitin (like insect shells) instead of cellulose. They also don't photosynthesize. Biology is less about "rules" and more about "strategies for survival."

Essential Differences Summary

- Shape: Plants are fixed and rectangular; animals are irregular and fluid.

- Energy: Plants use chloroplasts AND mitochondria; animals only use mitochondria.

- Storage: Plants have one massive central vacuole; animals have several small ones.

- Structure: Plants have a cell wall; animals have an extracellular matrix for support.

How to Actually Use This Information

Knowing the parts of a cell isn't just for passing a test. It’s the foundation of modern medicine. When doctors design antibiotics, they often target the cell wall of bacteria. Since human (animal) cells don't have cell walls, the medicine can kill the bacteria without hurting you.

If you're trying to memorize these for an exam or a project, don't just look at the labels. Draw them. There is something about the physical act of drawing the double membrane of a nucleus or the folds (cristae) of a mitochondrion that locks the info into your brain better than any flashcard.

Next Steps for Mastering Cell Biology

- Identify the specimen: If you’re looking through a microscope, look for the cell wall first. If it looks like a brick wall, it’s a plant.

- Focus on the DNA: Locate the nucleus. In many plant cells, the large vacuole pushes the nucleus to the side, whereas in animal cells, it’s often more central.

- Check for "extras": See any cilia or flagella (tail-like structures)? That’s almost certainly an animal cell or a very specific type of plant sperm.

- Use 3D models: If the 2D diagram isn't clicking, find a 3D simulation online. Seeing how the ER wraps around the nucleus in three dimensions makes the spatial relationship much clearer.

Understanding the labeled diagram of animal and plant cell is basically learning the vocabulary of life. Once you know the parts, you can start asking the bigger questions—like how these tiny bags of salt water eventually teamed up to create something as complex as a human being.