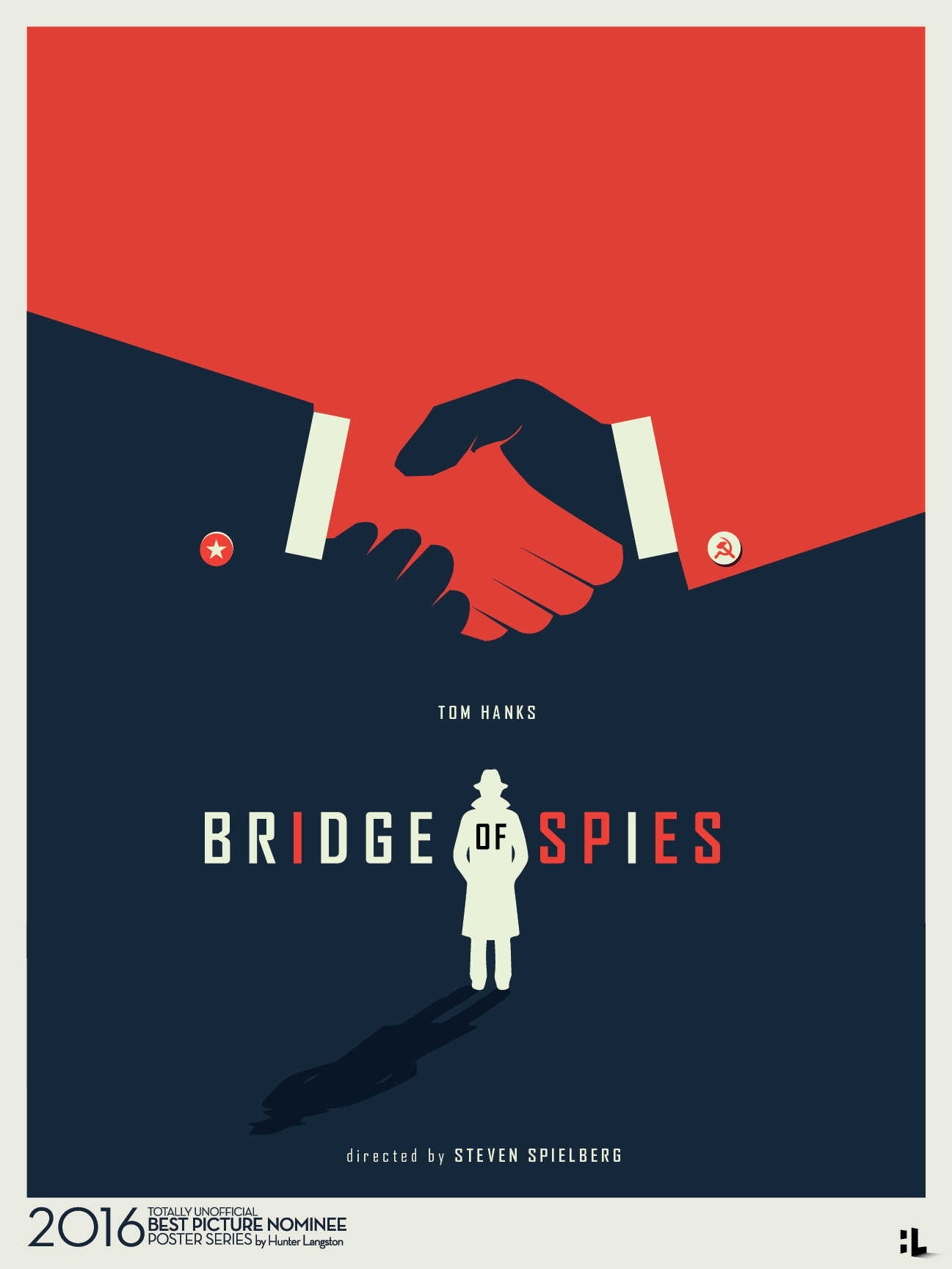

If you’ve ever fallen down a Wikipedia rabbit hole after watching a Tom Hanks movie, you aren't alone. Specifically, people keep searching for the spy org. in Bridge of Spies NYT crossword clues and historical deep dives because the reality of the Cold War was actually weirder than the movie. We’re talking about the KGB. The Committee for State Security.

It wasn't just some vague "bad guy" agency.

Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies focuses on the 1962 exchange of Rudolf Abel for Francis Gary Powers. While the movie is a masterclass in tension, the actual mechanics of the spy org. in Bridge of Spies NYT readers often look up—the KGB—were far more bureaucratic and terrifyingly efficient than a two-hour runtime can fully capture. You’ve got the CIA on one side, trying to play by a set of rules that they're basically inventing as they go, and the KGB on the other, operating with a level of domestic and international reach that would make modern data brokers blush.

The KGB: More Than Just a Crossword Answer

The KGB was founded in 1954, but its roots go way back to the Cheka. By the time Rudolf Abel—real name William Fisher—was painting in a cluttered Brooklyn apartment, the KGB was the "sword and shield" of the Communist Party. They didn't just spy on Americans. They spied on everyone. Neighbors. Poets. Their own officers.

Abel was a "Colonel." Or so the story goes. Honestly, his rank and his role were shrouded in so much Soviet compartmentalization that even the FBI wasn't 100% sure what they had when they busted him in 1957. He was part of the "Illegals" program. These weren't diplomats with "get out of jail free" cards. These were deep-cover operatives living mundane lives, waiting for the signal to do something massive.

The spy org. in Bridge of Spies NYT mentions is often framed through the lens of the "Hollow Nickel Case." That’s a real thing. A newsboy in Brooklyn dropped a nickel, it popped open, and there was a microfilm inside. It took the FBI four years to crack the code. That is the level of tradecraft we’re talking about. It wasn't flashy. It was tedious.

🔗 Read more: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Why the CIA Struggled with the Abel Exchange

The CIA is the other side of the coin. In the film, they’re portrayed as somewhat cold and pragmatic, which, let’s be real, is pretty accurate for 1960s Langley. When Francis Gary Powers was shot down in his U-2 spy plane over Sverdlovsk, the CIA was caught in a massive lie. They claimed it was a weather plane. Then Nikita Khrushchev produced the pilot. Alive.

It was a total disaster for Eisenhower.

James B. Donovan, the lawyer played by Hanks, had to navigate the ego of the CIA and the stubbornness of the KGB. The CIA didn't necessarily want Powers back because they loved him; they wanted to know how much he’d told the Soviets. They were terrified he hadn't used his "suicide pin"—a modified silver dollar containing saxitoxin. He hadn't. He chose to live.

This created a weird moral friction. The KGB respected Abel because he stayed silent. The CIA was suspicious of Powers because he survived.

The Glienicke Bridge: The Cold War's Most Iconic Set Piece

You can still visit the bridge today. It connects Potsdam with Berlin. During the Cold War, it was the perfect "no man's land."

💡 You might also like: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

The spy org. in Bridge of Spies NYT buffs love to discuss is the Stasi, the East German secret police. In the movie, they’re the ones complicating the deal by holding Frederic Pryor, an American student. This highlights a crucial historical nuance: the KGB didn't always get along with its satellite agencies. The Stasi wanted recognition as a legitimate state organ. The KGB just wanted their man (Abel) back.

Donovan’s genius was realizing he could play these two "allied" spy organizations against each other. He knew the Soviets looked down on the East Germans. He used that friction to get two Americans for the price of one Russian. It was a high-stakes poker game played in the freezing rain of a divided Germany.

Fact vs. Fiction: What the Movie Tweaked

Look, Spielberg is a storyteller. He needs drama.

- The Courtroom Heat: In the movie, Donovan is a pariah. His house is shot at. While there was public outcry, the real James Donovan was a highly respected figure who had been an associate general counsel for the OSS (the precursor to the CIA). He wasn't just some "insurance lawyer" who stumbled into the lion's den. He was a seasoned intelligence insider.

- The Conditions of Abel’s Detention: Abel was treated relatively well. The US government wanted to flip him. They didn't just want to punish him; they wanted his brain. He never cracked. Not once.

- The Pryor Release: The release of Frederic Pryor happened at Checkpoint Charlie, not the Glienicke Bridge. The movie merges these for cinematic effect, but in reality, Donovan was running back and forth between two different locations in a divided city.

The Legacy of the 1962 Exchange

Why do we still care about this specific spy org. in Bridge of Spies NYT reference? Because it represents the peak of "gentlemanly" espionage. There were rules. You don't kill the lawyers. You trade the pieces.

Today, espionage is digital. It's signals intelligence (SIGINT) and hacking. But back then, it was human intelligence (HUMINT). It was about the strength of a man’s character in a concrete cell. Rudolf Abel became a hero in the Soviet Union, eventually featured on a postage stamp. Francis Gary Powers returned to a cold reception, only to be exonerated years later.

📖 Related: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

The story reminds us that behind the massive, faceless machines of the CIA and the KGB, there were individuals making impossible choices.

How to Research Cold War Spy Craft Like a Pro

If you want to go deeper than the movie, you have to look at the primary sources. The NYT archives from 1957 to 1962 are a goldmine of contemporary fear and fascination.

- Read "Strangers on a Bridge": This is James Donovan's own memoir. It's incredibly detailed and lacks the Hollywood gloss, focusing more on the legal maneuvering.

- Analyze the U-2 Flight Logs: Declassified CIA documents now show exactly what Powers was seeing before he was hit by a surface-to-air missile.

- Study the "Illegals" Program: The KGB’s use of non-official cover (NOC) agents didn't end with Abel. It continued through the Cold War and arguably evolved into the sleeper cells discovered in the US in 2010 (the inspiration for The Americans).

- Visit the International Spy Museum: They actually have artifacts from the U-2 crash and tools used by KGB agents during that era.

The real "Bridge of Spies" wasn't just a physical structure. It was the back-channel communication that kept the world from blowing up during the most dangerous decade in human history. Whether you’re solving a crossword or writing a thesis, understanding the friction between the CIA and the KGB is the only way to make sense of the 20th century.

Take a look at the FBI’s "Vault" records on Rudolf Abel. You’ll see the actual photos of the hollowed-out bolts and pens he used to hide secrets. It’s way more grounded—and way more impressive—than any CGI.

Actionable Insight: To truly understand the era, compare the trial transcripts of Rudolf Abel with the public statements of the Soviet Foreign Ministry at the time. The gap between what was known and what was admitted is where the real history lives.