Thirteen seconds. That is all it took. In less time than it takes to tie your shoes, the trajectory of the American anti-war movement shifted forever. When the smoke cleared on the commons of an Ohio university on May 4, four students were dead, nine were wounded, and the nation's psyche was fractured in a way that hasn't fully healed even decades later. People talk about the Kent State shooting 1970 as this singular, isolated explosion of violence, but honestly? It was a slow-motion train wreck that started days earlier.

It wasn't just a "protest gone wrong." It was a failure of leadership, a breakdown in communication, and a terrifying example of what happens when exhausted, poorly trained young men with loaded semi-automatic rifles are dropped into a pressure cooker of political dissent.

The Weekend the Peace Died

You can't understand May 4 without looking at May 1. It was hot. Tensions over the Vietnam War were already at a boiling point, but then President Richard Nixon went on national television to announce the "Cambodian Incursion." To the students, this felt like a betrayal. They thought the war was winding down; instead, it was expanding.

Friday night in downtown Kent was messy. People were drinking, a bonfire was lit in the street, and windows were smashed. It was rowdy, sure, but it wasn't a revolution. Yet, the local mayor, Leroy Satrom, got spooked. He declared a state of emergency. This is where the dominoes started falling. By Saturday night, the ROTC building on campus was in flames. To this day, nobody is 100% certain who started that fire, though plenty of fingers point at radical agitators. Regardless of who struck the match, the sight of that burning building was the justification Governor James Rhodes needed to send in the Ohio National Guard.

When the Guard arrived, they weren't just there to keep the peace. They were tired. They had been on duty elsewhere dealing with a massive trucking strike. They were operating on little sleep and even less patience.

Monday Morning: The Chaos on the Commons

By Monday, May 4, the university had tried to ban the scheduled noon rally. It didn't work. Roughly 2,000 people gathered anyway. Some were there to scream about the war, but honestly, many were just walking to their next class or eating lunch, watching the spectacle from the sidelines.

The National Guard, led by General Robert Canterbury, decided the crowd had to disperse. They fired tear gas. The wind, being uncooperative, blew the gas right back at the Guardsmen or sent it harmlessly away from the crowd. Students threw the canisters back. There was shouting. There were rocks thrown—though the severity of the "rock rain" is still debated by eyewitnesses like then-student Alan Canfora.

The Guard marched the protesters across the commons, over a hill known as Blanket Hill, and down toward a practice football field. Then, they realized they were essentially boxed in by a fence. They retreated back up the hill.

Then, it happened.

Near the Pagoda at the top of Blanket Hill, members of Troop G turned nearly in unison. They pointed their M1 Garand rifles. They fired.

Who Were the Victims?

It’s easy to look at the Kent State shooting 1970 as a statistic, but the names matter because they weren't all "radicals."

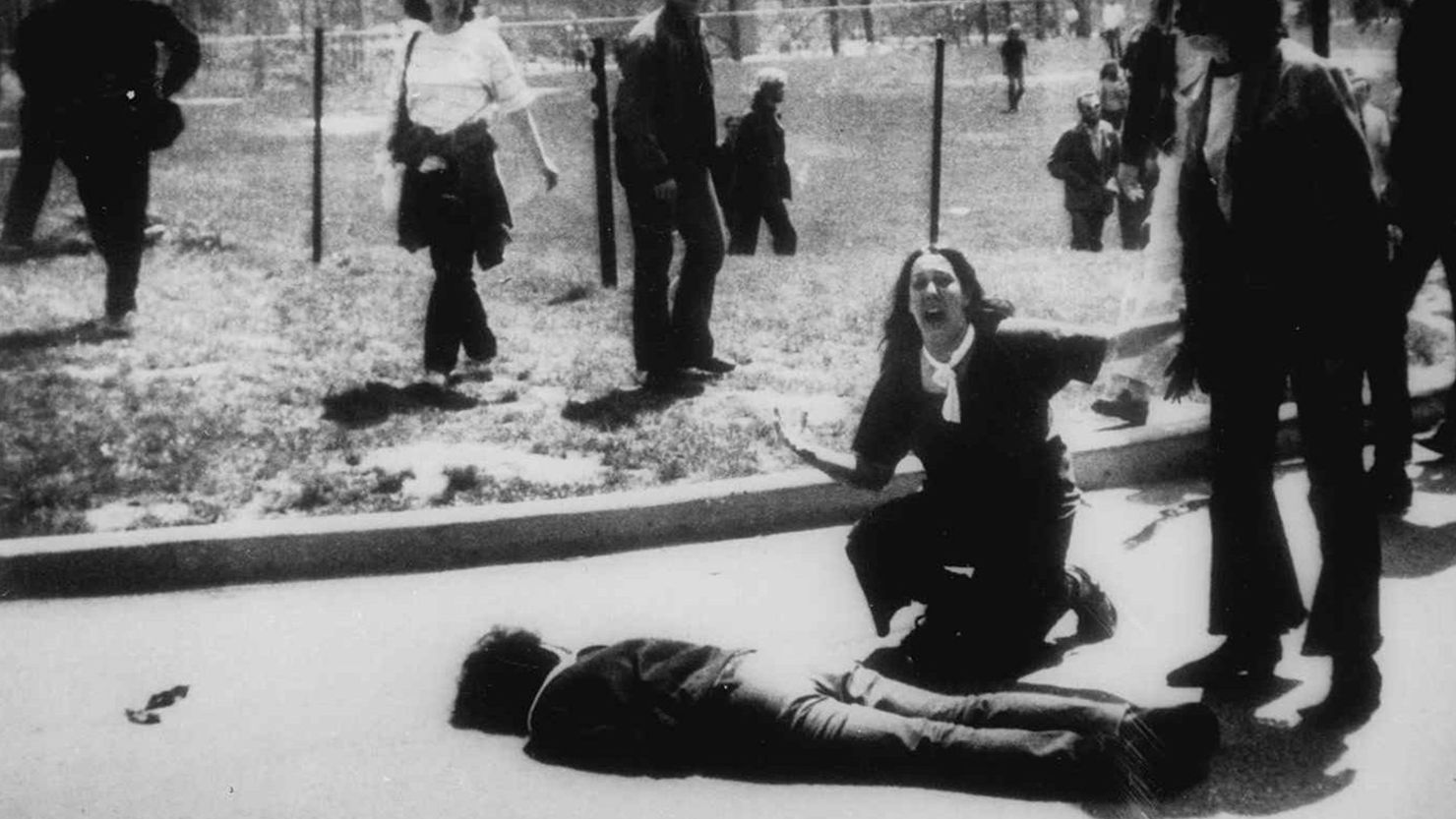

- Jeffrey Miller: He was shot through the mouth and died instantly. He was about 265 feet from the Guard.

- Allison Krause: She had reportedly put a flower in a Guard's rifle the day before, saying "Flowers are better than bullets." She was 343 feet away.

- William Schroeder: Here is the kicker—Schroeder was an ROTC student. He wasn't even protesting. He was walking to class when a bullet hit him in the back.

- Sandra Scheuer: She was also just walking to class. She was 390 feet away from the rifles.

One student, Dean Kahler, was paralyzed from the waist down. The distance is what haunts you when you stand on that field today. These kids weren't lunging with bayonets. They were football fields away.

The Great Mystery: Was There an Order to Fire?

For years, the official line was that the Guardsmen fired because they feared for their lives. But if you look at the photos—like the Pulitzer Prize-winning shot by John Filo of Mary Ann Vecchio screaming over Miller's body—you don't see a Guard unit being overrun. You see a unit in control.

In 2007, a digital forensic analysis of the "Strubbe tape"—a reel-to-reel recording made by a student from a dorm window—suggested something chilling. Some experts, like Stuart Allen, claimed they could hear a voice yelling, "Point! Check point! Fire!" before the volley of shots. The Department of Justice looked into it again in 2012 but ultimately said the recording was too "inconclusive" to reopen the case.

Whether it was a command or a single panicked soldier pulling a trigger that triggered a chain reaction, the result was 67 bullets in 13 seconds.

✨ Don't miss: US Bombs Iran Today: What’s Actually Happening and Why the Headlines Might Be Misleading

The Aftermath and the "Silent Majority"

You’d think the country would have unified in grief. It didn't.

Actually, the reaction was horrifyingly divided. A Gallup poll taken shortly after the massacre showed that a huge portion of Americans blamed the students for their own deaths. Kent State faculty members reported receiving letters saying "more of them should have been shot." It was a moment that exposed a massive, bleeding rift in American society—the "Generation Gap" wasn't just a catchy phrase; it was a war zone.

The event triggered the only nationwide student strike in U.S. history. Over 4 million students walked out. Hundreds of colleges closed. The Nixon administration was rattled, leading to the creation of the Scranton Commission, which eventually called the shootings "unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

Why Kent State Still Matters in 2026

We live in an era of heightened protest. We see campus demonstrations every week on the news. The Kent State shooting 1970 serves as a permanent warning about the militarization of domestic protest response. It’s the reason why the rules of engagement for the National Guard were overhauled. It’s the reason we question the use of lethal force in "crowd control."

When you strip away the politics, it’s a story about the fragility of the First Amendment. It’s about how quickly a democratic society can slip into a state of lethal force against its own children.

How to Properly Research the Event Today

If you really want to get into the weeds of what happened, don't just read a textbook. The archives are deep.

- Visit the May 4 Visitors Center: If you're ever in Ohio, go. They have mapped out exactly where every person stood. Seeing the distance between the Pagoda and Sandra Scheuer’s final resting place changes your perspective instantly.

- Listen to the Oral Histories: Kent State University maintains an incredible digital archive of interviews with survivors, Guardsmen, and townspeople. The nuance is in their shaking voices.

- Read "Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio" by Derf Backderf: It’s a graphic novel, but don't let that fool you. It is one of the most meticulously researched accounts of the four days leading up to the shooting.

- Analyze the Trials: Look into the 1975 civil trial. The victims' families eventually settled for a measly $675,000 and a "statement of regret" from the defendants. It wasn't an apology. It was a legal maneuver. Understanding that lack of closure explains why the wound is still open for many survivors.

The legacy of that Monday in May isn't just a song by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. It's a reminder that the rights we take for granted—to assemble, to speak, to dissent—were paid for in blood on a grassy hill by people who were just trying to get to their 1:00 PM chemistry lecture.