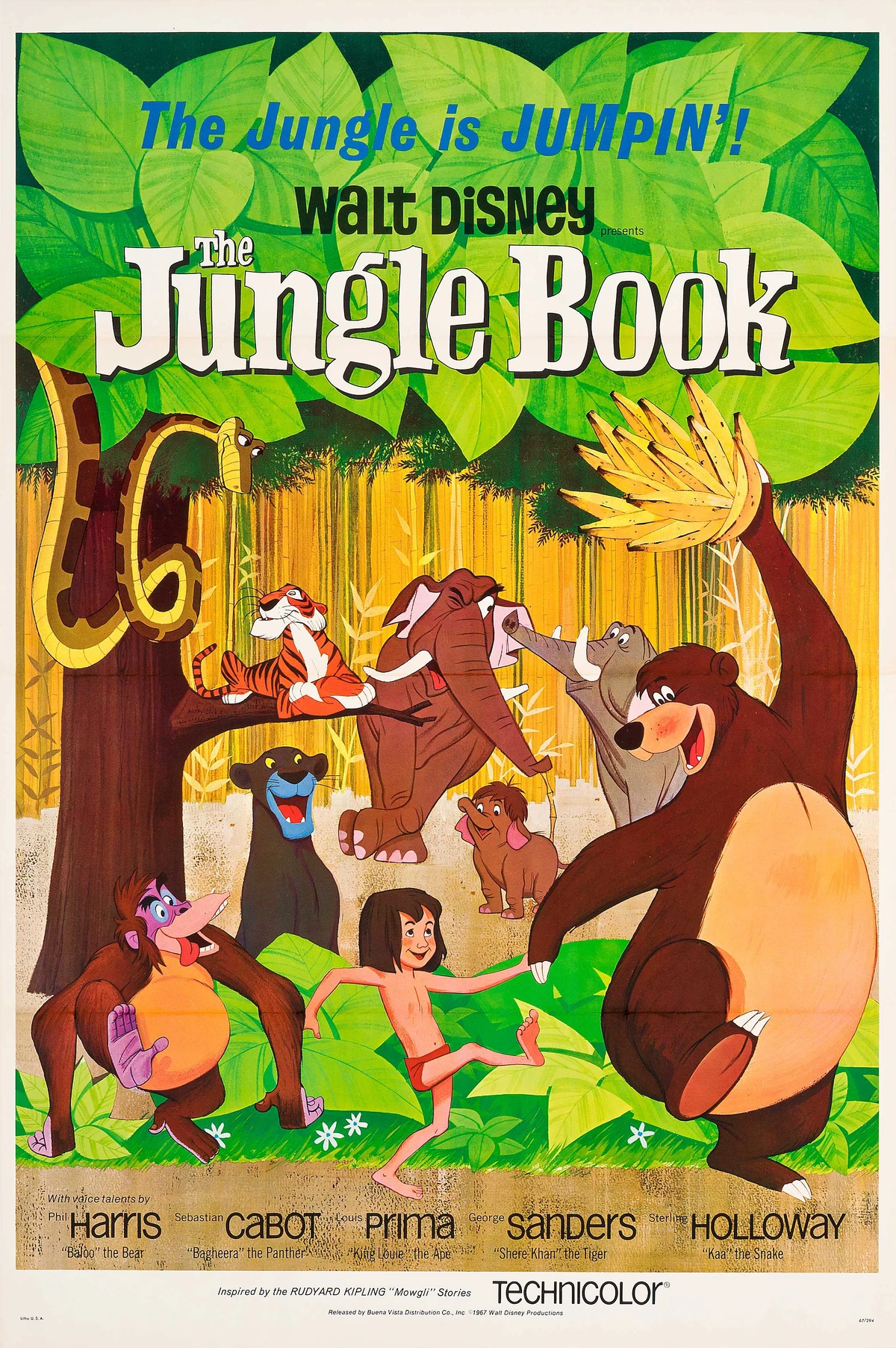

You’ve probably seen the Disney movies. Maybe you’ve even read the original Rudyard Kipling stories where Mowgli runs with the wolves and avoids the sharp claws of Shere Khan. But here’s the thing: the Jungle Book jungle isn’t some made-up fantasy world like Middle-earth or Narnia. It’s a real place. Specifically, it’s a sprawling, rugged, and intensely beautiful landscape in the heart of India.

Kipling wasn't just guessing when he wrote about the Seoni region. He was describing a very specific ecosystem that still breathes today, even if it's under more pressure than it was in the late 1800s. If you go there now, you won't find a talking bear singing about "Bear Necessities," but you will find the actual teak forests and rocky ravines that inspired the greatest animal stories ever told.

The Real Seoni: Mapping the Jungle Book Jungle

The heart of the Jungle Book jungle is located in the Seoni District of Madhya Pradesh, India. If you look at a map of central India, you’ll see a massive green belt. This is the Satpura Range. It’s a land of "ghats"—steep hills—and deep valleys where the Wainganga River snakes through the terrain.

Most people assume Kipling spent his whole life trekking through these woods. Honestly? He never actually visited Seoni. That’s the wild part. He lived in India as a young man, but he wrote The Jungle Book while living in Vermont, USA. He used the detailed journals and photographs of British officers, specifically Robert Armitage Sterndale and James Forsyth, to reconstruct the landscape. Forsyth’s book, The Highlands of Central India, acted as a blueprint for Mowgli’s world. It’s a testament to Kipling’s genius that he could evoke the humidity and the smell of the damp earth so well without standing in that specific patch of dirt.

The primary setting for the Jungle Book jungle today is preserved within Pench National Park. It’s a mix of dry deciduous forest and open grasslands. In the summer, the heat is brutal, turning the foliage into a brittle, golden brown. But when the monsoon hits, the place explodes into a neon-green wilderness that feels ancient. It’s exactly the kind of place where a "Man-cub" could get lost and never want to be found.

Shere Khan’s Territory vs. Modern Reality

When you think of the Jungle Book jungle, Shere Khan is the looming shadow. In the book, he’s a "Lungri"—a lame tiger with a limp—which makes him more desperate and dangerous. In the real forests of Madhya Pradesh, the Royal Bengal Tiger is still the king, but the power dynamic has shifted.

💡 You might also like: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

Back in the 1890s, tigers were seen as pests or trophies. Today, they are the focus of one of the most intense conservation efforts on the planet. Pench, along with the nearby Kanha National Park (which many also associate with the stories), serves as a critical tiger corridor. These aren't isolated islands of trees; they are connected pathways that allow big cats to roam.

The "Council Rock" where Akela led the wolf pack is thought to be inspired by the real-life rocky outcrops found throughout the Seoni district. There's a specific spot called Turiya that looks remarkably like the descriptions in the text. It’s surreal to stand there. You half-expect to see a black panther sliding through the shadows of a ghost tree.

Ghost trees (Sterculia urens) are a real feature of the Jungle Book jungle. They have pale, white bark that looks like skeletal arms reaching out in the moonlight. Kipling used this eerie atmosphere to build tension. It’s not just a backdrop; the forest is a character.

The Misconception of the "Tropical" Jungle

One of the biggest mistakes people make—mostly thanks to the 1967 cartoon—is thinking the Jungle Book jungle is a tropical rainforest like the Amazon. It’s not.

Central India is characterized by "Teak and Sal" forests. These trees lose their leaves in the dry season. It’s not always lush and dripping with water. For a good portion of the year, it’s a harsh, dusty environment. This makes the struggle for water a central theme in Kipling’s work, specifically the "Water Truce" during a great drought. This is a real ecological phenomenon. When the Wainganga River runs low, predators and prey are forced into a tense proximity at the few remaining watering holes.

📖 Related: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

The biodiversity is staggering. You have:

- Sloth Bears: The real-life Baloo. They aren't jolly teachers; they are actually quite grumpy and can be more dangerous than tigers if startled.

- Indian Wolves: These are smaller and scrappier than their North American cousins. They hunt in the scrublands.

- Black Panthers: Bagheera is actually a melanistic Indian leopard. They are rare, but they do exist in these woods, their spots barely visible beneath a coat of midnight black.

- Dholes: The "Red Dogs" that Mowgli feared. They are savage, highly organized hunters that can take down prey much larger than themselves.

Why the Jungle Book Jungle Matters in 2026

We are currently living in a time where these real-world locations are under immense pressure. Linear infrastructure—roads and railway lines—threatens to chop the Jungle Book jungle into pieces. If the tiger corridors are cut, the genetic diversity of the species fails.

The "Law of the Jungle" wasn't just a catchy phrase Kipling made up. It was a reflection of the delicate balance of an ecosystem. "The strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack." That’s basically an early lesson in interdependence. If the deer population vanishes, the tiger enters the village. If the river is dammed, the forest dies.

Tourism in Pench and Kanha has become a double-edged sword. On one hand, the money from "Mowgli-themed" safaris funds the forest guards who protect the animals from poachers. On the other hand, too many jeeps can stress the wildlife. It’s a constant tug-of-war between sharing the magic and preserving the silence.

Practical Steps for Exploring the Seoni Landscape

If you want to experience the Jungle Book jungle without the Hollywood filter, you have to be intentional about how you visit. It’s not a theme park. It’s a working wilderness.

👉 See also: Pic of Spain Flag: Why You Probably Have the Wrong One and What the Symbols Actually Mean

Choose the right entry point. Pench National Park is the most direct link to Seoni. The Turia Gate is the most popular, but if you want a quieter experience that feels more like the "untouched" woods Mowgli would have known, try the Karmajhiri Gate.

Timing is everything. The parks are usually closed during the monsoon (July to September) because the roads become impassable. The best time for wildlife sightings is from February to June. It’s hot. You’ll be sweaty. But as the water dries up, the animals congregate at the banks of the Pench River.

Look for the small things. Don't just chase tigers. The Jungle Book jungle is alive with Indian Rollers (birds with brilliant blue wings), Langur monkeys who act as the forest's alarm system, and the "Bandar-log"—the unruly macaques.

Understand the human element. The Gond people are the indigenous inhabitants of this region. Kipling’s stories often touched on the friction between the village and the wild. Many of the guides in Pench today are Gonds who have lived alongside these tigers for generations. Their knowledge is deeper than any guidebook.

Wildlife Etiquette in Mowgli’s Home

- Keep it quiet. Shouting "Look, Shere Khan!" is the fastest way to make sure you see nothing but a disappearing tail.

- Respect the buffer zones. Stay in the designated vehicles. The animals aren't tame; they’ve just learned that the green jeeps aren't a threat.

- Carry out what you carry in. Plastic is a poison in the Seoni woods.

The Jungle Book jungle is a place of shadows and light, governed by rules that are millions of years old. Whether you call it the Seoni Highlands or Pench, the reality is far more impressive than the fiction. It’s a place where the "Red Flower" (fire) is still feared and where the call of the peacock marks the end of the day.

To truly understand the story, you have to see the teak trees silhouetted against a central Indian sunset. You have to hear the warning bark of a spotted deer. Only then does the Law of the Jungle start to make sense.

Actionable Insights for the Aspiring Explorer

If you're planning to dive into the world that inspired Kipling, start by reading the 1894 original text alongside a modern topographical map of Madhya Pradesh. Focus your travel research on the "Tiger Circuit," which includes Pench, Kanha, and Bandhavgarh. Support lodges that employ local villagers, as this reduces the human-wildlife conflict that Kipling so vividly described. By choosing eco-conscious operators, you ensure that the Jungle Book jungle remains standing for the next generation of "Man-cubs" to wonder at.