You probably picture Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as these stoic, marble-statue figures standing on a cliffside, pointing heroically toward the Pacific. It’s the classic American myth. But if you actually sit down and read the journals of Lewis and Clark, the reality is much messier. It’s sweatier. It’s full of bad spelling, constant mentions of "portable soup," and a surprising amount of complaining about mosquitoes.

History is often sanitized. We get the highlights—the big map, the meeting with Sacagawea, the "Ocean in view! O! the joy!" moment. But the roughly million words scrawled into those leather-bound notebooks tell a story that isn't just about discovery. It’s a survival log. It’s a scientific data dump. Honestly, it’s a bit of a miracle those pages even made it back to Washington D.C. in one piece.

The Raw Reality of the Expedition

When Thomas Jefferson sent the Corps of Discovery out in 1804, he wasn't just looking for a path to the sea. He wanted data. He wanted to know about every plant, every animal, and every tribe. He basically gave Lewis a crash course in botany and celestial navigation and said, "Write everything down."

And they did.

The journals of Lewis and Clark aren't just one book. They are a collection of diaries, field notes, and scraps written by several members of the party, though Lewis and Clark did the heavy lifting. If you’ve ever looked at a transcript, the first thing you notice is the spelling. William Clark was a brilliant navigator, but he could spell the word "Soux" (Sioux) about twenty different ways in a single week. It’s endearing, really. It reminds you that these weren't scholars in a library; they were exhausted men writing by firelight with mosquitoes buzzing in their ears.

Actually, the mosquitoes are a recurring theme. They mention them constantly. It sounds trivial until you realize they were trekking through wetlands where the swarms were so thick they could barely breathe. It’s these tiny, gritty details that make the journals feel alive. You aren't reading a dry history; you're reading the frustrations of men who are cold, hungry, and very far from home.

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The Scientific Weight of the Ink

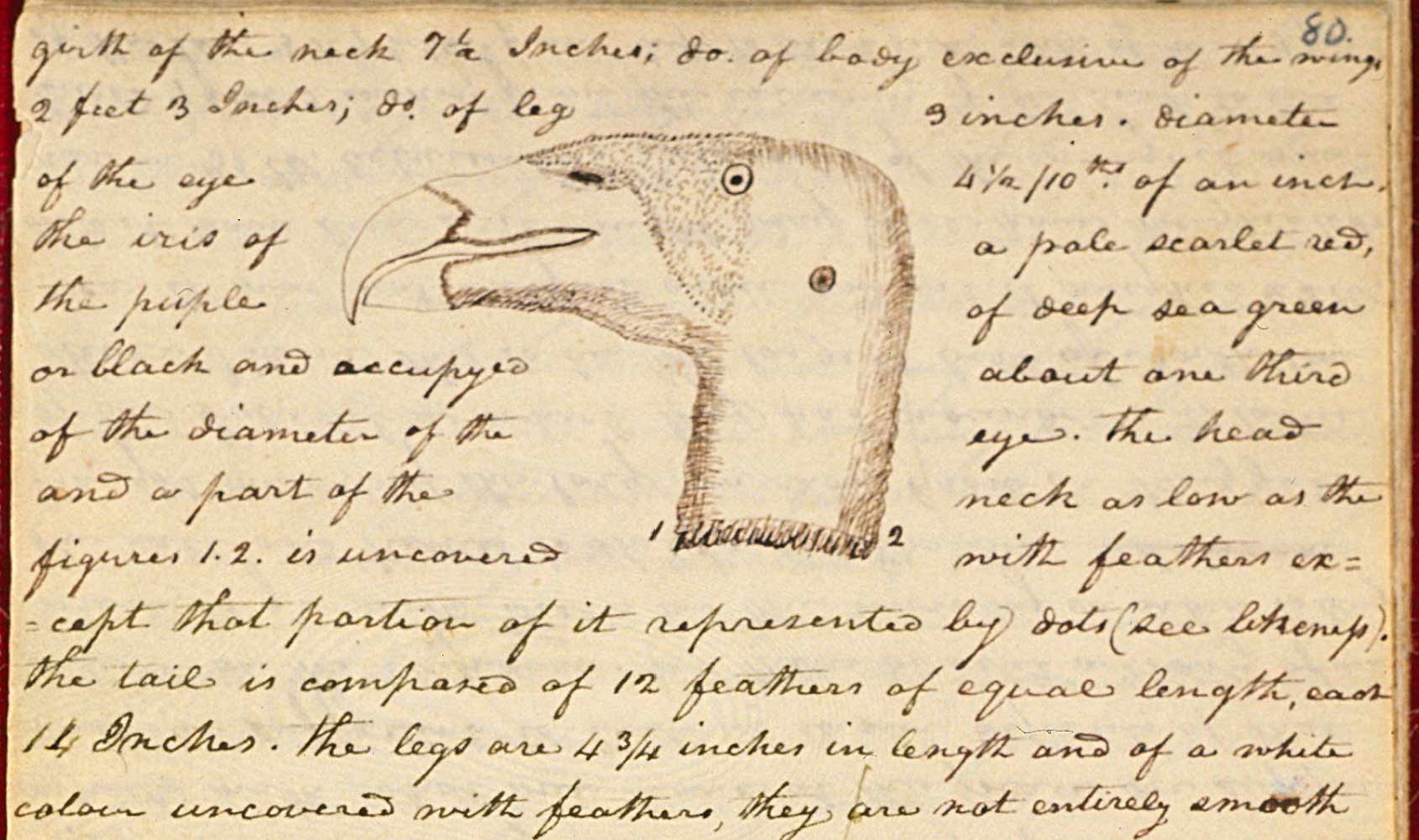

We often focus on the geography, but the biological record is staggering. Before this trip, white Americans had no idea what a grizzly bear really was. They’d heard rumors, sure. But Lewis provides these terrifyingly detailed descriptions of being chased by "tremendous" bears that wouldn't die even after being shot multiple times.

He describes the prairie dog—which he called a "barking squirrel"—with the meticulous eye of a biologist. He’s looking at the teeth, the fur texture, the social behavior.

- He recorded 122 species of animals.

- He identified 178 plants.

- He tracked weather patterns daily.

This wasn't just a hike. It was a rolling laboratory.

Why the Journals of Lewis and Clark Almost Disappeared

It’s kind of a miracle we can read these today. After the expedition returned in 1806, the journals didn't just go to a printer. Life got in the way. Lewis was supposed to edit them, but he struggled with what many historians now believe was deep depression. He never finished the task before his mysterious death at a wayside inn in 1809.

Clark was left to pick up the pieces. He eventually handed them over to Nicholas Biddle, who produced a narrative version in 1814. But here’s the kicker: Biddle cut out a lot of the science. He focused on the adventure. The original, raw journals—the ones with the maps and the botanical sketches and the "vulgar" details of daily life—sat in various archives for decades.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

It wasn't until the early 1900s, and later the definitive Reuben Gold Thwaites edition, that the public really got to see the unvarnished words. We almost lost the most important primary source in American expansion because of a mix of tragedy and editorial "cleanup."

Sacagawea through Their Eyes

There’s a lot of myth-making around Sacagawea. In the journals, she isn't some mystical guide leading them by divine intuition. She’s a teenager with a newborn baby who is incredibly observant.

The journals mention her recognizing landmarks in her home territory, which was vital. But more importantly, the journals note that her presence served as a "white flag." A war party doesn't travel with a woman and an infant. Her presence signaled peace to the tribes they encountered. Clark clearly grew fond of her and her son, Jean Baptiste (whom he nicknamed "Pomp"), but the journals also show the stark reality of her status as a Shoshone woman living among the Hidatsa and then the Corps.

The Darker Side of the Pages

We have to be honest here. The journals reflect the era's attitudes. While Lewis and Clark often expressed genuine admiration for the sophisticated cultures of the Nez Perce or the Mandan, the underlying mission was always about American sovereignty. They were telling these tribes that they had a new "Great Father" in the East.

There’s a tension in the writing. One day Lewis is praising the hospitality of a village, and the next he’s writing about his distrust of another group. It’s a complicated, often contradictory record of the first contact between the U.S. government and the indigenous peoples of the West. If you read between the lines, you see the seeds of the conflicts that would define the next century.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

The Mystery of Lewis’s Silence

One of the strangest things about the journals of Lewis and Clark is the "gap." For long stretches of the journey, Lewis just... stops writing. Clark is the steady one. He writes every day, even if it’s just about the weather or what they ate. But Lewis, the more poetic and descriptive writer, goes silent for months.

Why?

Some historians think he was too busy. Others think his mental health was fluctuating. When he does write, his prose is beautiful, almost haunting. When he doesn't, the silence is loud. It makes you realize how much of this journey was an internal struggle as much as a physical one.

Practical Ways to Engage with the Journals

If you’re interested in this, don't just buy a "Best Of" book. Go to the sources.

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln has digitized the entire thing. You can search for specific dates or keywords. If you want to see what they were doing on your birthday in 1805, you can. It’s a rabbit hole. You start looking for "grizzly bears" and end up reading three hours of notes about how to fix a leaky dugout canoe.

What to Look For:

- The Salmon Descriptions: When they hit the Columbia River, the sheer volume of fish they describe is hard to fathom today.

- The Winter at Fort Clatsop: They spent the winter in present-day Oregon. It rained almost every single day. Their clothes were literally rotting off their backs. Their frustration in the journals is palpable.

- The Maps: Clark’s hand-drawn maps are surprisingly accurate. Looking at them side-by-side with modern satellite imagery is wild.

The journals of Lewis and Clark serve as a time capsule of a continent on the verge of massive change. They are messy, biased, incredibly detailed, and deeply human. They remind us that history isn't a straight line; it's a series of daily decisions made by people who were often tired, scared, and just trying to get to the next campsite.

To truly understand this period, stop looking at the monuments and start reading the mud-stained notes.

Actionable Next Steps

- Visit the Digital Archive: Go to the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition website hosted by the University of Nebraska. Search for "July 4, 1805" to see how they celebrated Independence Day in the wilderness.

- Check Out the Maps: Look specifically at William Clark's 1814 map. It was the first to give the American public a semi-accurate look at the Rockies and the river systems of the West.

- Read the Non-Captain Perspectives: Look for the entries of Sergeant Patrick Gass. He was the first to publish his journal, and his perspective is much more "working class" compared to the officers.

- Visit the Trail: If you're in the Pacific Northwest or the Missouri River area, use the National Park Service's Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail app to find the exact spots described in the journals. Seeing the "White Cliffs" of the Missouri in Montana while reading Lewis’s description of them is a top-tier travel experience.