History books usually focus on the numbers. 2,209 dead. 20 million tons of water. 40 feet high. But if you actually look at the Great Flood of 1889, it wasn't just some freak act of nature or a "sad thing that happened" in Pennsylvania. It was a massive, avoidable catastrophe fueled by a mix of gross negligence, bad engineering, and a very specific kind of 19th-century arrogance.

It rained. A lot. But rain doesn't just erase a whole city from the map.

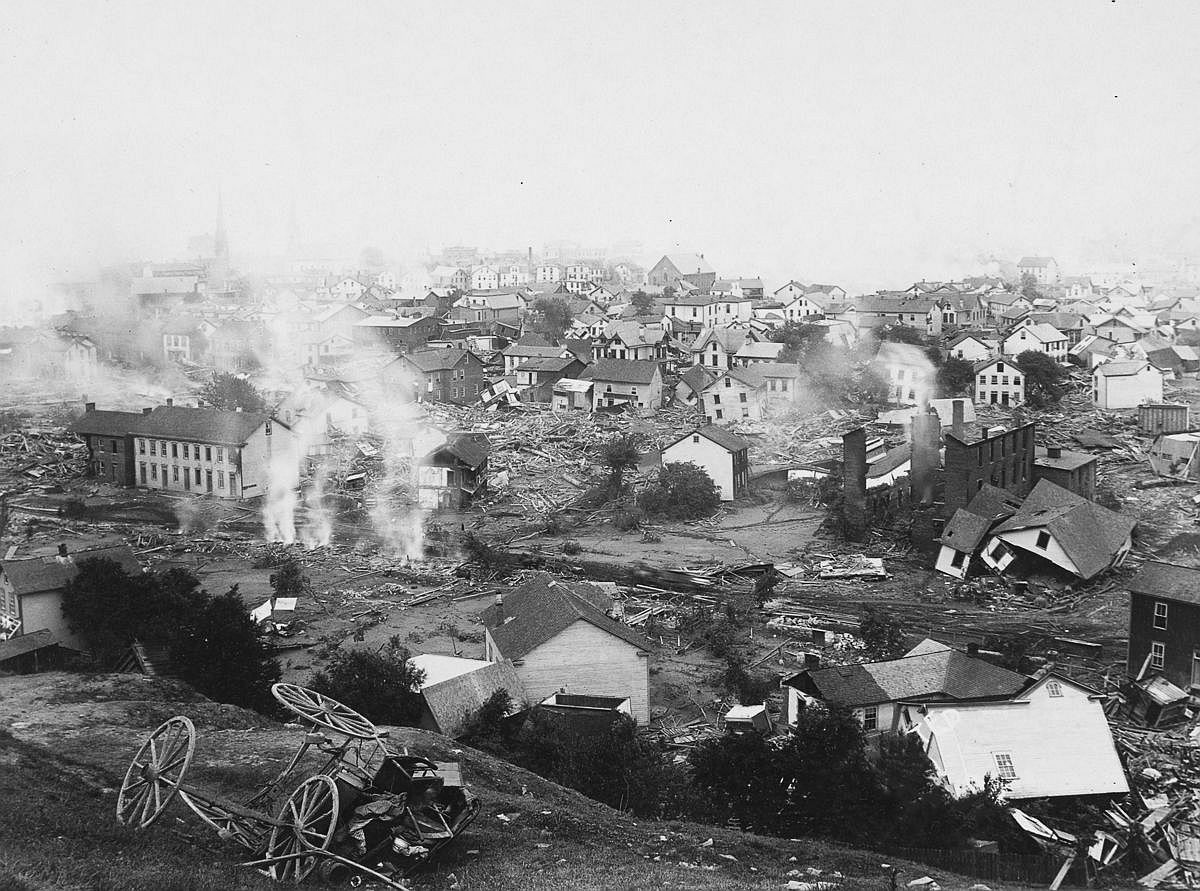

Basically, what happened in Johnstown was the result of a playground for the ultra-wealthy—the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club—failing to maintain a dam they knew was shaky. When the South Fork Dam finally gave way on May 31, 1889, it didn't just leak. It collapsed. A wall of water the size of a mountain roared down the Little Conemaugh River, picking up houses, trains, and people like they were pieces of glitter in a windstorm. Honestly, the scale is hard to wrap your head around even now.

The dam that should have never held water

You've got to understand the South Fork Dam. It was originally built by the state of Pennsylvania as part of a canal system, then abandoned, then eventually bought by a group of wealthy tycoons from Pittsburgh. We’re talking big names here—Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon. These guys wanted a mountain retreat. They called it the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club.

To make their private lake, they "repaired" an old, breached dam. But "repaired" is a strong word for what actually happened.

They lowered the top of the dam so their carriages could pass each other more easily. They failed to replace the discharge pipes that would have let them lower the water level during a storm. Most importantly, they put fish screens over the spillway. Why? Because they didn't want their expensive game fish escaping. During the Great Flood of 1889, those screens did exactly what you’d expect: they caught debris, clogged up, and turned the spillway into a useless pile of sticks and mud.

The water had nowhere to go but over the top. Once an earthen dam is overtopped, it’s over. The water eats the dirt. The structure dissolves.

🔗 Read more: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

John Parke, the young engineer at the lake that morning, saw it coming. He tried to warn people. He sent telegrams. But Johnstown had heard "the dam is breaking" so many times over the years that most people just went back to their lunch. They thought it was just another false alarm. They were wrong.

The moment the world ended for Johnstown

At 3:10 PM, the dam vanished.

Imagine 20 million tons of water suddenly moving at 40 miles per hour. It didn't look like a wave in a movie. Survivors described it as a rolling mountain of black death, filled with trees, locomotives, and the crushed remains of every town upstream of Johnstown.

By the time the Great Flood of 1889 hit the city itself, it wasn't just water. It was a battering ram. The debris—houses, barbed wire from the local mills, animals—mashed together into a "muck" that leveled everything in its path. When the surge hit the Stone Bridge in Johnstown, the debris piled up and actually caught fire. People who had survived the water were trapped in the wreckage and burned to death because the mass of wood and oil was too dense for rescuers to reach them.

It’s grim. It’s horrific. And it’s the reason the American Red Cross, led by Clara Barton, became a household name. This was their first major peacetime relief effort. Barton stayed for five months, proving that her organization could handle domestic disasters just as well as it handled the carnage of the Civil War.

Why the death toll was so high

- The geography: Johnstown sits in a deep river valley. It's basically a funnel.

- The timing: It was a Friday afternoon. Families were home.

- The debris: Most people weren't drowned by water; they were crushed by houses or strangled by miles of loose barbed wire from the Gautier Wire Works.

- Communication: The telegraph lines went down early, leaving the city blind to the wall of water screaming toward them.

The legal battle that changed nothing (and everything)

After the Great Flood of 1889, everyone expected the rich guys at the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club to pay. They didn't.

💡 You might also like: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

Under the laws of the time, the club members weren't held personally liable. The courts ruled the disaster an "Act of God." People were furious. How could a man-made dam, maintained by billionaires, be considered an act of God when the locals had been pointing out the leaks for years?

This injustice actually sparked a massive shift in American law. It led to the eventual adoption of "strict liability," the idea that if you engage in an activity that is inherently dangerous—like holding back a massive lake with a questionable dirt wall—you are responsible for the damages if things go sideways, regardless of whether you were "negligent" in the traditional sense.

Misconceptions about the Great Flood of 1889

A lot of people think the flood was a one-time thing. Actually, Johnstown has flooded several times since, notably in 1936 and 1977. But 1889 is the one that sticks because of the sheer violence of the event.

Another myth is that the "rich guys" didn't care at all. Some did. Carnegie, for instance, helped fund the library and the reconstruction. But many locals felt it was "blood money" intended to mask the fact that their families had been wiped out for the sake of a summer resort.

The lake is gone now. If you visit the Johnstown Flood National Memorial today, you can stand in the "breach"—the empty space where the dam used to be. You can see the remnants of the abutments and look down the valley toward where the town once stood. It is hauntingly quiet.

Essential facts for researchers

If you are looking into the specifics for a project or family history, here are a few things to keep in mind:

📖 Related: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

- The Great Flood of 1889 happened on May 31.

- The city was an industrial powerhouse, specifically for steel and iron.

- The flood remains one of the deadliest non-natural disasters in U.S. history.

- The "Stone Bridge" still stands today. It’s a literal monument to the tragedy.

Lessons you can actually use

While the Great Flood of 1889 feels like a distant historical footnote, the lessons are surprisingly relevant to our current world of infrastructure and corporate responsibility.

First, never ignore "nuisance" warnings. The citizens of Johnstown had become desensitized to flood warnings. If you live in a high-risk area, whether for floods, fires, or storms, have a "go-bag" and a communication plan that doesn't rely solely on the grid.

Second, look at your local infrastructure. We often assume that because a bridge or a dam is there, it's being maintained by experts. The 1889 disaster proved that sometimes, the people in charge are just hobbyists or cutting corners to save a buck. Check your local flood maps and dam safety reports.

Third, support organizations like the Red Cross before the disaster happens. Their work in 1889 set the template for how we respond to crises today.

If you want to see the impact firsthand, your next step should be a visit to the Johnstown Flood Museum in Pennsylvania. They have a preserved 1889 "debris" house and a massive relief map that shows the water's path. It’s one thing to read about it; it’s another to see the physical height of the water marked on the side of a building. You can also dig through the digitized survivor accounts at the National Park Service website to hear the stories in the victims' own words.