You’ve seen them. Those minimalist rectangles of gravel with a few jagged rocks and some meticulously wavy lines. Maybe you saw one in a corporate lobby or a high-end spa and thought, "That looks peaceful." But honestly? A real japanese zen rock garden—properly known as karesansui—was never meant to be a "relaxation station." It’s actually closer to a psychological obstacle course.

It’s dry. It’s harsh. It’s literally translated as "dry mountain water." These gardens don't use a single drop of liquid to represent the ocean. Instead, they use crushed granite or pebbles to trick the brain into seeing movement where there is only stillness. It’s a bit of a mind game, really.

I’ve spent time at Ryōan-ji in Kyoto, arguably the most famous site for this stuff. People sit on the wooden veranda for hours, staring at fifteen rocks. Here’s the kicker: from any angle you sit, you can only see fourteen of them at once. One is always hidden. That’s not an accident. It’s a deliberate architectural flex meant to remind us that as humans, we never have the full picture. Our perspective is always limited.

The Myth of the "Zen" Meditation Room

We need to clear something up right away. The term "Zen garden" is actually a bit of a Western invention. If you go to Japan and ask for a "Zen garden," people will know what you mean, but the historical term is karesansui. These gardens first gained massive traction during the Muromachi period (1336–1573).

Back then, Zen Buddhism was becoming the backbone of Japanese culture. Samurai loved it. Why? Because Zen is about discipline, facing reality without blinking, and stripping away the fluff. A japanese zen rock garden wasn't a place to go take a nap or scroll through your phone. It was a tool for kōan study—meditation on paradoxes that can't be solved by logic.

Imagine being a monk in the 1400s. Your job is to rake that gravel every single morning. If your mind wanders for one second, the line goes crooked. The physical act of raking is the meditation. It’s not about the "finished" look of the gravel; it’s about the fact that you have to do it again tomorrow because the wind or a bird will mess it up. It’s a lesson in impermanence.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

Why Stones Aren't Just Stones

In a japanese zen rock garden, the rocks are the stars. But you can't just throw any backyard pebble in there. Professional garden designers, or ishidate-so (monks who "set stones"), look for specific qualities. They categorize rocks based on their "energy" or shape.

- Some stones are "Tall Vertical." They represent trees or upright humans.

- Others are "Flat," acting as the earth or the floor of the sea.

- "Reclining" stones look like animals or low hills.

There is a legendary manual called the Sakuteiki, written in the 11th century. It’s basically the bible of Japanese gardening. It warns that if you set a stone incorrectly—like placing a "fainting" stone upright—you'll bring bad luck or even death to the owner. That sounds dramatic, but it shows how much weight they put on the visual balance.

Musō Soseki, a famous Zen master and garden designer, believed that gardens were a way to express the landscape of the mind. When you look at the rocks at Saihō-ji, you aren't looking at geology. You're looking at Soseki’s internal architecture. It’s deep stuff.

Raking the Gravel: The Physics of "Water"

The sand isn't actually sand. Most authentic gardens use shirakawa, which is weathered granite from the Shirakawa River in Kyoto. It’s heavy enough that the wind won't blow it away instantly, and it has this beautiful grey-white shimmer.

Raking this material is a workout. You use a heavy wooden rake with wide teeth.

The patterns matter.

Straight lines usually represent calm water or the "void."

Circular ripples around the rocks? Those are waves hitting an island.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

You’ve probably seen those tiny desktop "Zen gardens" with the little plastic rakes. Honestly, those are fine for stress, but they miss the scale. In a real japanese zen rock garden, the scale is meant to overwhelm the ego. When the "waves" in the gravel are two inches deep and stretch for thirty feet, it stops being a hobby and starts being a landscape.

The Error of Perfection

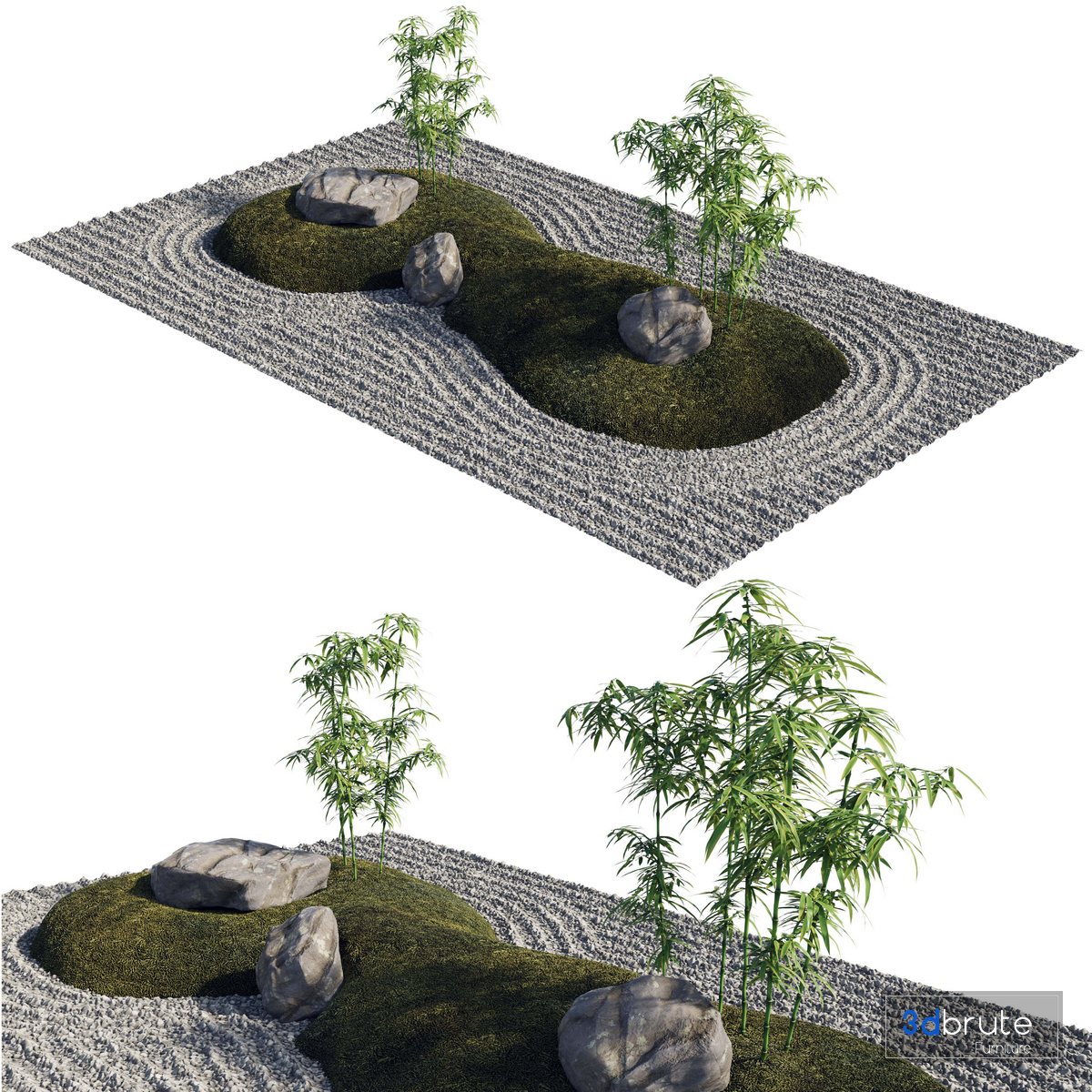

One of the biggest mistakes people make when trying to understand these spaces is looking for "pretty" flowers. There are no flowers. Maybe some moss if the climate allows it. Moss represents age and humidity, providing a contrast to the dry, sterile gravel.

This ties into the Japanese concept of Wabi-sabi. It’s the appreciation of things that are imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. A rock with a crack in it is more valuable than a perfectly smooth one because the crack tells a story of time.

If you visit the Daitoku-ji temple complex, you’ll see gardens that look "unfinished." That’s the point. A garden that is "perfect" is dead. A garden that leaves room for the viewer to fill in the blanks is alive.

Modern Interpretations and Urban Sanctuaries

Today, the japanese zen rock garden has migrated out of temples and into skyscrapers. Architects like Tadao Ando use these principles to create "pockets of silence" in busy cities. You don't need a monastery to have one.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Even in a small backyard in a suburb, the principles apply. It’s about subtraction. Most Western gardens are about addition—more flowers, more colors, more mulch. Zen gardening is about seeing how much you can take away until only the essence remains.

How to Actually Use Zen Garden Principles at Home

If you're looking to bring this vibe into your life, don't just buy a kit. Think about the "void." In Japanese aesthetics, this is called Ma. It’s the space between things. It’s the silence between notes in music.

- Pick a Focal Point. Don't clutter the space. One or three rocks (odd numbers are key) are better than a dozen.

- Focus on Texture. Use different sizes of gravel. Contrast the rough surface of a stone with the smooth, raked lines of the "water."

- Control the View. Zen gardens are often meant to be viewed from a specific spot, like a window or a bench. Don't worry about how it looks from the "top down." Focus on the perspective from where you actually sit.

- Maintenance as Mindfullness. Don't view the weeding or the raking as a chore. If you hate the upkeep, don't build the garden. The upkeep is the garden.

The real power of a japanese zen rock garden is that it doesn't demand anything from you. It doesn't smell like roses; it doesn't give you fruit. It just sits there, reflecting whatever state of mind you brought with you.

If you’re frustrated, the rocks look jagged and cold.

If you’re calm, they look like islands of stability in a chaotic sea.

The next time you see those ripples in the gravel, remember: they aren't there to look pretty for a photo. They are there to show you the path of the rake, the hand of the person who moved it, and the fleeting nature of the present moment. Once you stop looking for "beauty" and start looking for "truth," the garden finally starts to make sense.

Go find a quiet spot. Look at a single stone. Notice the lichen. Notice the shadows. That’s where the real Zen happens.