If you ask most people in the West when World War II started, they’ll probably say September 1939. Poland. Blitzkrieg. That whole thing. But if you’re looking at the actual scale of global conflict, that date is honestly pretty late to the party. For millions of people in Asia, the nightmare actually kicked off two years earlier.

The invasion of China 1937 wasn't just some regional skirmish that got out of hand. It was a massive, brutal, and incredibly complex total war that fundamentally reshaped the modern world. We're talking about the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the fall of Shanghai, and a level of human suffering that's honestly hard to wrap your head around. It’s the "Forgotten Holocaust" or the "War before the War," depending on which historian you’re reading.

Basically, by the time Hitler’s tanks rolled into Poland, China had already been fighting for its life for over 700 days.

The Spark: What Really Happened at Marco Polo Bridge?

History books like to point to July 7, 1937. It’s the "official" start. But the vibe in Northern China had been tense for years before that. Japan had already snatched Manchuria in 1931, setting up a puppet state called Manchukuo. They were hovering. They were waiting.

The actual trigger was almost absurdly small. A Japanese soldier named Private Shimura Kikujiro went missing during a night maneuver near the Lugou Bridge (the Marco Polo Bridge) outside Beijing. The Japanese demanded entry into the town of Wanping to search for him. The Chinese refused. Shots were fired.

Here’s the kicker: Shimura actually showed up a bit later. He wasn't kidnapped; he’d basically just gotten lost or had a "bathroom emergency," depending on whose account you believe. But by the time he wandered back, the wheels of the invasion of China 1937 were already turning. Japan didn't want an apology; they wanted an excuse.

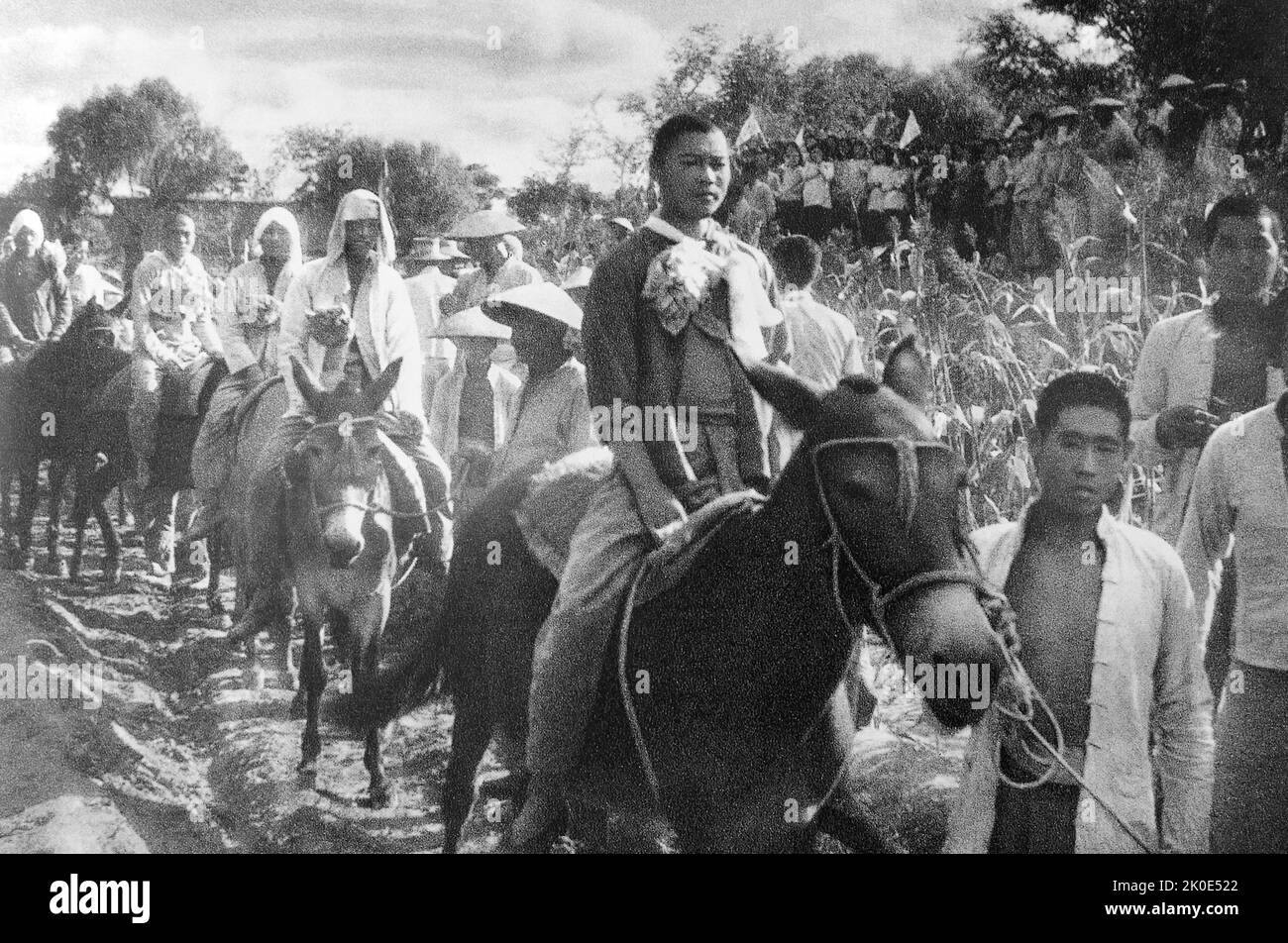

Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), finally decided he couldn't retreat anymore. He’d been criticized for years for "appeasing" Japan while he fought the Communists. But 1937 was the breaking point. He basically said, "That's it," and the regional conflict turned into a full-scale national war of survival.

✨ Don't miss: Who Is More Likely to Win the Election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Shanghai: The "Stalingrad on the Yangtze"

Most people think of the early war as a Japanese cakewalk. It wasn't.

When the fighting spread to Shanghai in August 1937, it turned into one of the bloodiest urban battles in human history. Chiang Kai-shek threw his best troops—divisions trained by German advisors—into the meat grinder. He wanted to show the world that China would fight. He wanted international intervention.

It was brutal.

House-to-house fighting. Sniper fire. Constant Japanese naval bombardment from the Whangpoo River. The Chinese held out for three months, which shocked the Japanese military command, who had boasted they would "finish China in three months" total. By the time Shanghai fell in November, the casualties were staggering. China lost about 250,000 men. Japan lost over 40,000.

The psychological impact was huge. It proved the invasion of China 1937 was going to be a long, agonizing slog, not a quick colonial takeover. It also forced the Chinese government to start moving its entire industrial base—literally dismantling factories and carrying them on backloads—deep into the interior to Chongqing.

The Horror of Nanjing and the "Great Migration"

After Shanghai fell, the Japanese Imperial Army headed for the capital, Nanjing. What happened next is one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century. When the city fell in December 1937, the restraint of the Japanese military completely evaporated.

🔗 Read more: Air Pollution Index Delhi: What Most People Get Wrong

Historians like Iris Chang, who wrote The Rape of Nanking, documented the systematic slaughter and sexual violence that occurred over six weeks. While some Japanese revisionists still try to downplay the numbers, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East estimated over 200,000 civilians and prisoners of war were murdered. It was an atrocity that stayed in the collective memory of China forever.

But there’s another side to the invasion of China 1937 that people forget: the refugees.

Imagine millions of people—somewhere between 80 to 100 million—fleeing westward. It was the largest forced migration in history. Students carried library books across mountains. Farmers pulled carts. It was a nation in motion, trying to stay ahead of an advancing army. This "Free China" in the west became the holdout that Japan simply couldn't crack.

Why Japan Couldn't Actually "Win"

On paper, Japan should have won. They had better planes, better tanks, and a professional navy. China was fractured, poor, and technically in the middle of a civil war between the Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists.

But China is big. Really big.

The Japanese could take the cities and the railroads, but they couldn't control the countryside. They were like a "power grid" that only powered the lines but left the rest of the room in the dark. The Chinese used "Scorched Earth" tactics. In 1938, Chiang Kai-shek even ordered the breaking of the Yellow River dikes to stop the Japanese advance. It worked, but it also drowned hundreds of thousands of his own people and created a massive famine.

💡 You might also like: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

It was a total war where human life was treated as a secondary concern to national survival. Japan got bogged down in what historians call the "quagmire." They were winning battles but losing the war of attrition.

The Geopolitical Shift

The invasion of China 1937 is what eventually led to Pearl Harbor. Japan needed oil and rubber to keep their war machine in China running. When the U.S. finally slapped an oil embargo on Japan in 1941 to force them out of China, Japan felt they had to strike south into Southeast Asia to grab resources. To do that, they had to take out the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

So, in a very real way, the bullets fired at the Marco Polo Bridge in 1937 led directly to the bombs dropped on Hawaii in 1941.

Realities vs. Myths

- Myth: The Chinese didn't fight back until the U.S. joined.

Reality: China fought alone for four years. They suffered millions of casualties before the first Flying Tiger ever took to the sky. - Myth: The Communists did all the fighting.

Reality: The KMT (Nationalists) took the brunt of the heavy, conventional battles. The Communists focused on guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. Both were essential, but the KMT lost the vast majority of the professional soldiers. - Myth: Japan had a unified plan.

Reality: The Japanese Army and Navy hated each other. Often, officers on the ground in China would start "incidents" without permission from Tokyo just to force the government’s hand.

How to Understand This History Today

If you’re trying to wrap your head around modern East Asian politics, you have to understand 1937. The scars are still there. The tension between Beijing and Tokyo often traces back to how this war is remembered—or forgotten—in textbooks.

To get a deeper look, check out these resources:

- "Forgotten Ally" by Rana Mitter: This is basically the gold standard for understanding China's role in WWII. It’s readable and debunks the idea that China was just a passive victim.

- The Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall: If you're ever in China, this site is heavy, but it's essential for seeing how the event is memorialized today.

- Documentaries: Search for footage of the Battle of Shanghai. The scale of the ruins looks like something out of Berlin 1945, but it happened years earlier.

The invasion of China 1937 changed the trajectory of the 20th century. It weakened the Nationalists enough that the Communists could eventually win the civil war in 1949. It ended the era of European colonial dominance in Asia. And it left a legacy of trauma that still dictates how billions of people interact today.

To truly grasp the significance of this period, your next step should be looking into the United Front. This was the shaky, "frenemy" alliance between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists. Understanding how they paused their civil war to fight Japan—while still secretly plotting against each other—explains a lot about why China looks the way it does today. Look into the Xi'an Incident for the specific turning point where Chiang Kai-shek was essentially kidnapped and forced to fight the Japanese. It's one of the wildest "truth is stranger than fiction" moments in history.