It happened in 2006. June 28th, to be exact. Senator Ted Stevens, an 82-year-old Alaskan who headed the Senate Commerce Committee, stood up to talk about net neutrality. He was frustrated. He was trying to explain why a massive movie file shouldn't be allowed to slow down everyone else's email. Then, he said it. The phrase that would launch a thousand memes and define boomer tech-illiteracy for a generation: "The internet is a series of tubes."

The "Daily Show" went wild. Jon Stewart spent nearly ten minutes tearing the speech apart. Wired laughed. Silicon Valley cringed. To the tech-savvy youth of the mid-2000s, Stevens sounded like a man describing a car as a "fast metal box with circles on the bottom." He seemed hopelessly lost in an era of fiber optics and packets.

But here’s the thing. If you actually look at the physical infrastructure of the web today, Stevens wasn't nearly as wrong as we all thought.

What the Senator Actually Said (And Why It Mattered)

We remember the "tubes" part. We usually forget the rest of the rambling speech. Stevens was describing a situation where his staff sent him an "internet" (he meant an email) on a Friday, and he didn't receive it until Tuesday. He argued that the "tubes" were clogged.

"It's not a big truck," he famously added.

Honestly, as a metaphor for bandwidth congestion, it's pretty solid. In networking, we talk about "pipes." We talk about "throttling." We talk about "flow control." If you replace the word "tubes" with "circuits" or "fiber-optic channels," the Senator suddenly sounds like a Cisco engineer. He was grappling with the concept of asynchronous transfer and the physical limitations of hardware.

The internet isn't some magical, ethereal cloud. It’s a massive, tangible, vibrating mess of glass and copper. It requires literal space. It requires cooling. It requires physical protection from sharks—yes, real sharks—that occasionally bite the undersea cables connecting continents.

The Physical Reality of the Series of Tubes

If you want to see the internet is a series of tubes in real life, you have to go to places like 60 Hudson Street in New York or the Equinix data centers in Northern Virginia. These are "carrier hotels." Inside, you won't find clouds. You'll find miles of yellow plastic trays. These trays carry fiber-optic cables.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

Each cable is a tube.

Inside that tube are strands of glass as thin as human hair. These strands carry light. When those "tubes" get full, or when the routers at the end of them can't process the light fast enough, things slow down. That’s exactly what Stevens was complaining about. He just used "senator-speak" to describe a very real engineering bottleneck.

The Undersea Backbone

Think about the MAREA cable. It’s a joint project between Microsoft and Meta. It stretches 4,100 miles across the Atlantic. It’s essentially a massive, reinforced pipe resting on the ocean floor. Inside are eight pairs of fiber-optic cables.

When a person in London clicks a link to a server in Virginia, data literally travels through that tube. It’s not a metaphor. It’s a 10-million-pound physical object. When a ship drags an anchor and snaps one of these, an entire country can lose its connection. In 2008, multiple cables in the Mediterranean were cut, reportedly by anchors, causing massive outages across Egypt and India.

The "tubes" broke.

Why the Meme Persisted

The mockery didn't happen because Stevens was technically wrong about the physics. It happened because he was trying to use that misunderstanding to justify a "tiered" internet. He was arguing that companies like Comcast should be allowed to charge more to "clear the tubes" for certain traffic.

This was the birth of the Net Neutrality debate.

🔗 Read more: Heavy Aircraft Integrated Avionics: Why the Cockpit is Becoming a Giant Smartphone

The tech community feared that if we accepted the internet is a series of tubes analogy, we’d accept a world where the "tube owner" gets to decide who passes through. It felt like an old man trying to apply 19th-century railroad laws to 21st-century data.

Packet Switching vs. Circuit Switching

The real nuance Stevens missed—and the reason people called him a fool—is packet switching.

In an old-school phone line (circuit switching), you literally had a dedicated "tube" for your call. If you weren't talking, that tube stayed open and empty. The internet is smarter. It breaks your data into tiny packets. These packets find whatever "tube" is open at that millisecond. They might take different routes and reassemble at the end.

Stevens thought his email was stuck behind a "movie" like a car stuck behind a truck. In reality, his email packets were likely weaving around the movie packets. The delay he experienced probably had more to do with his own office’s mail server or a local ISP configuration than a global "clog."

The Modern "Tube" Crisis: 2026 and Beyond

Today, we’re seeing a resurgence of the Stevens philosophy, though nobody calls it that anymore.

With the rise of 8K streaming, generative AI training, and massive cloud gaming, the physical infrastructure is being pushed to the brink. We are building more "tubes" than ever. Starlink is essentially creating a series of "invisible tubes" via laser links in vacuum space.

- Submarine Cable Growth: We are adding roughly 30-40 new undersea cables a year.

- Data Center Power: These hubs now consume nearly 2% of global electricity.

- Latency Wars: High-frequency traders spend millions to shave 3 milliseconds off their "tube" travel time.

We’ve moved from his 2006 confusion to a 2026 reality where the physical constraints of the internet are the primary bottleneck for AI development. You can't train a massive language model if you can't move the data fast enough between GPU clusters. The "tubes" are the limit.

💡 You might also like: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

What We Get Wrong About Digital Space

We love the word "wireless." It feels clean. It feels like magic. But wireless is only the last hundred feet. Your 5G signal travels from your phone to a tower, and from that tower, it goes right back into—you guessed it—a physical fiber-optic tube.

The internet is arguably the largest machine ever built by humans. It is a singular, interconnected mechanical entity. When we treat it as an abstract concept, we ignore the environmental cost of the cooling systems and the geopolitical vulnerability of the cable routes.

Senators like Stevens were mocked for being "out of touch," but our modern tendency to ignore the physical reality of the web is its own kind of ignorance. We assume the "cloud" is infinite. It isn't. It's limited by the number of photons we can shove through a piece of glass at any given moment.

Actionable Insights for the Modern User

Understanding that the internet is a series of tubes isn't just a history lesson in memes; it changes how you should manage your own digital life.

- Hardwire when it matters. If you're gaming or on a critical video call, get off the Wi-Fi. A physical Ethernet cable is a dedicated "tube" to your router, eliminating the interference of airwaves.

- Check your "Last Mile." Most internet issues happen in the final stretch of cable to your house. If your speeds are low, it's rarely the "global tubes" that are clogged—it’s usually a degraded copper line or a bad splitter in your own basement.

- Support Infrastructure Transparency. Pay attention to where your data goes. Using local CDN (Content Delivery Network) nodes reduces the distance your data has to travel through the global "series of tubes," which lowers latency and reduces the energy footprint of your browsing.

- Acknowledge the Physical. Recognize that "deleting" something doesn't always remove its physical footprint in a data center. Every bit stored is a bit that requires a physical "tube" to be maintained and powered.

Ted Stevens died in a plane crash in 2010. He never really lived to see himself vindicated by the sheer physical scale of the modern web. He became a punchline, a symbol of a government that didn't understand the tools it was trying to regulate. But as we sit here in 2026, staring at a world connected by 1.4 million kilometers of undersea fiber, it's hard not to look at those cables and see exactly what he saw.

It's all just plumbing. It's all just tubes.

Next Steps for Deep Understanding

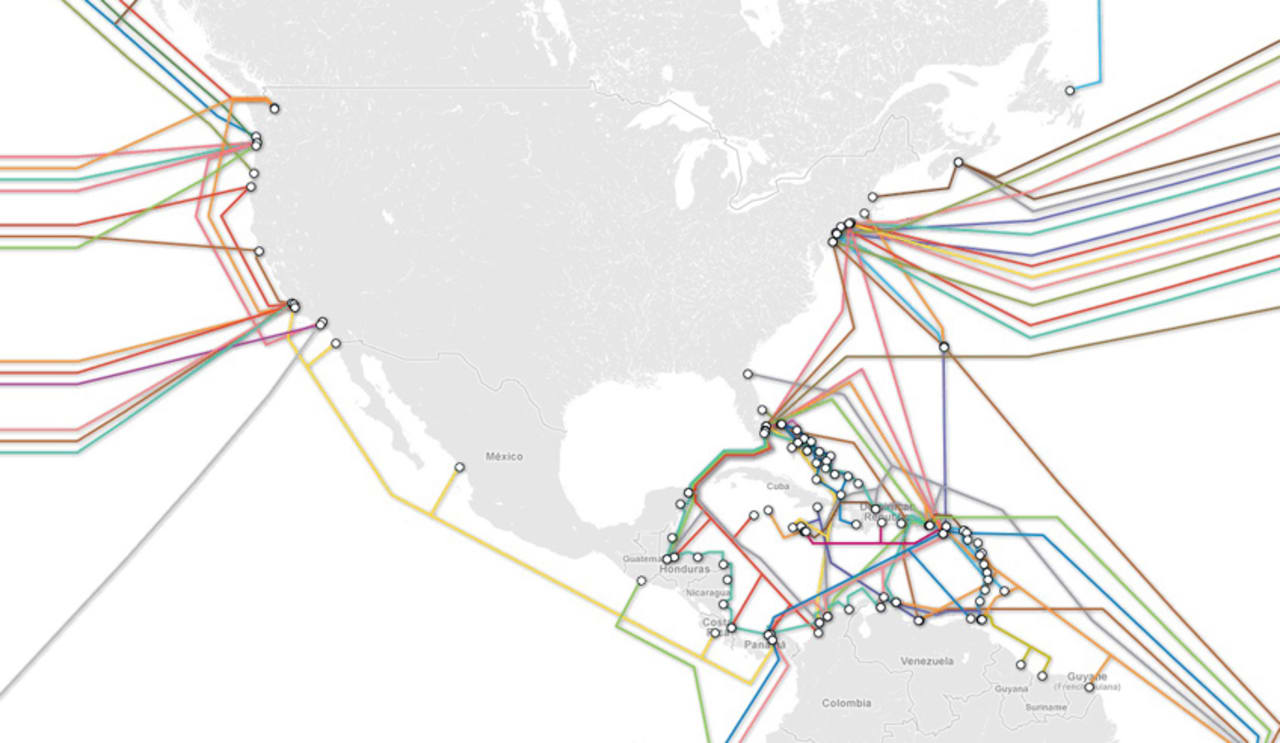

- Map the Cables: Visit the Submarine Cable Map to see the actual "tubes" connecting your country to the rest of the world.

- Test Your Throughput: Use a tool like Bufferbloat Test to see if your own "tubes" are getting clogged during high-traffic periods.

- Audit Your Hardware: Ensure your home router supports the latest standards (Wi-Fi 6E or 7) to prevent your local "tubes" from becoming the bottleneck for your fiber connection.