Ask ten different people for a definition for the internet and you’ll get ten answers that are technically right but practically useless. One guy might tell you it’s a "network of networks." Another might point at their phone and say "TikTok." Honestly, both are right, but they're talking about two completely different things. Most people confuse the "Internet" with the "Web," and while that sounds like nerd pedantry, knowing the difference is actually the first step to understanding how our entire modern civilization stays upright.

It’s big. Like, really big.

✨ Don't miss: Cell Phones Early 90s: Why Those Clunky Bricks Actually Changed Everything

We aren't just talking about cables and Wi-Fi signals. We’re talking about a global, decentralized architecture that allows billions of devices to speak the same language. It's the most complex thing humans have ever built, yet we treat it like a utility, no different from the water coming out of your kitchen tap. But water doesn't carry the sum total of human knowledge, and your sink doesn't let you trade cryptocurrency with someone in Tokyo.

What is the Actual Definition for the Internet?

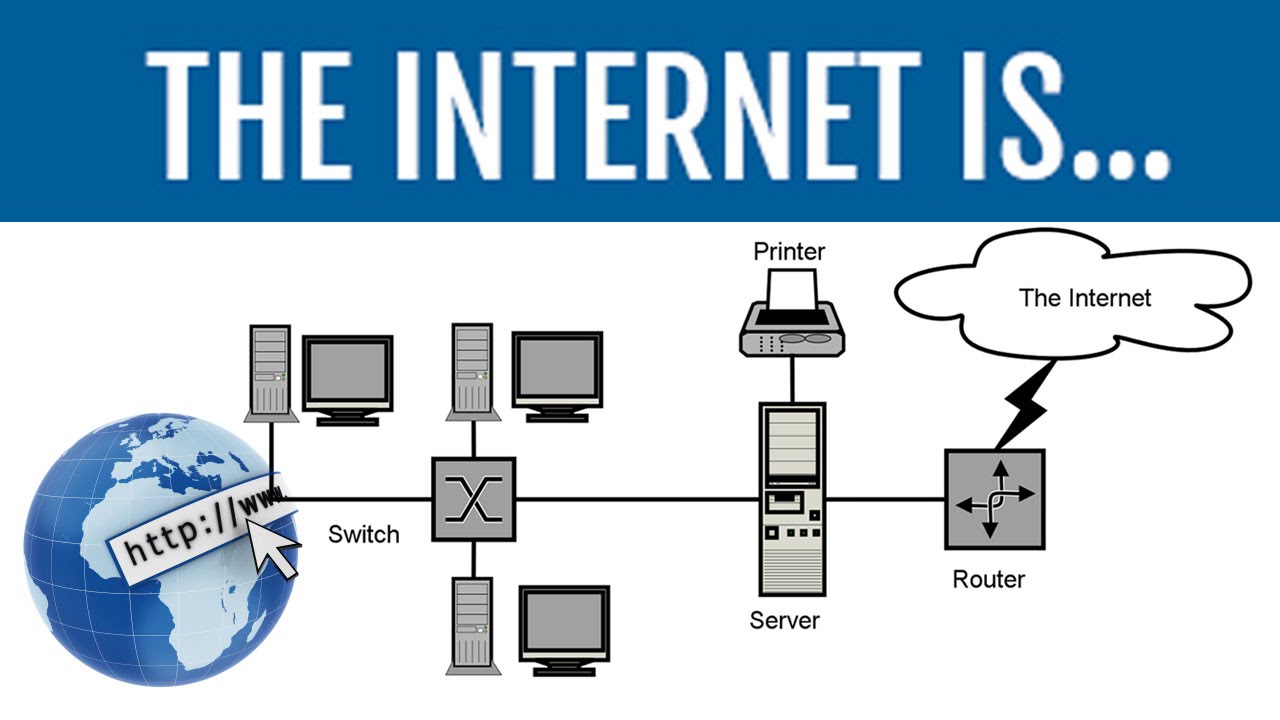

Strip away the apps, the browsers, and the streaming services. At its core, the definition for the internet is a global system of interconnected computer networks that use the Internet Protocol suite (TCP/IP) to link devices worldwide.

Think of it as the plumbing.

If the internet is the pipes, the World Wide Web is just the water flowing through them. Or, more accurately, the Web is just one type of thing that uses the pipes. Email, File Transfer Protocol (FTP), and even your smart fridge's firmware updates all use the internet, but they aren't "the web." Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn, the guys who basically invented the protocol, didn't build a library; they built a postal service that could deliver any kind of package to any address on earth instantly.

It’s Decentralized by Design

This is the part that blows people's minds. Nobody "owns" the internet. There is no "Off" switch located in a bunker in Virginia. Instead, it’s a massive cooperative of private, public, academic, and government networks. They are all linked by a broad array of electronic, wireless, and optical networking technologies.

It survives because of "routing." If one node goes down—maybe a shark chews through an undersea fiber-optic cable (which actually happens)—the data just finds a different path. It's like a traffic app rerouting you around a car wreck. This resilience was intentional. The early days of ARPANET were funded by the Department of Defense because they wanted a communication system that could survive a nuclear strike. Morbid, but effective.

The Hardware That Makes the Magic Feel Real

We tend to think of the internet as something "in the clouds." It isn't. It's heavy, it's hot, and it's mostly underwater.

If you want a real-world definition for the internet, look at the subsea cables. There are over 500 of them, some no thicker than a garden hose, draped across the ocean floor. They carry 99% of international data. Satellite internet like Starlink is cool, but it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the terabits per second moving through glass fibers at the bottom of the Atlantic.

The Power of the IP Address

Every single thing connected to this mess needs an address. That’s the IP (Internet Protocol) address. Originally, we used IPv4, which looked like 192.168.1.1. The problem? It only allowed for about 4.3 billion addresses. We ran out.

Now we use IPv6. These addresses are long strings of hexadecimal characters. How many are there? Roughly 340 undecillion. That is enough for every atom on the surface of the earth to have its own IP address and still have enough left over for another planet. This is what allows for the "Internet of Things." Your toaster, your car, and your doorbell all have a seat at the table because the internet’s "definition" of a user has expanded from "a scientist at a terminal" to "literally any object with a chip."

Why Your Browser Isn't the Internet

Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989 while working at CERN. He wanted a way for scientists to share documents easily. He created HTML, HTTP, and the first browser.

But remember: the internet had already been around for over a decade by then.

When you open Chrome or Safari, you are using an application to access a specific layer of the internet. You’re looking at "pages." But when you play Call of Duty online or send a message via WhatsApp, you aren't necessarily "on the web." You’re just using the internet's underlying transport layers to move data packets.

- The Internet: The hardware, the protocols, the cables, and the routers.

- The Web: The websites, the URLs, and the browsers.

- The Difference: One is the tracks; the other is the train.

The Social and Economic Reality

In 2026, the definition for the internet has shifted from a technical luxury to a human right. The UN has argued as much. Without it, you can't apply for most jobs, you can't do your taxes, and in many places, you can't even pay for groceries.

It’s a double-edged sword, though.

While it has democratized information—giving a kid in a rural village access to the same MIT lectures as a billionaire's son—it has also created echo chambers. The same protocols that allow for free speech also allow for the rapid spread of misinformation. The internet doesn't care if the data it’s moving is a cure for cancer or a conspiracy theory. It just moves the packets.

The Dark Web and the Deep Web

People get these confused all the time.

The "Deep Web" is just everything not indexed by Google. Your private emails, your bank account page, and your company’s internal database are all part of the Deep Web. It’s huge—way bigger than the surface web we see every day.

The "Dark Web" is a tiny sliver of the internet that requires specific software (like Tor) to access. It’s not inherently "evil," but its focus on anonymity makes it a haven for both dissidents living under dictatorships and, yeah, people selling things they shouldn't be selling.

How to Actually Use This Knowledge

Understanding a technical definition for the internet isn't just for trivia night. It changes how you troubleshoot your life. When your "internet is down," is it really the internet? Or is it just your DNS (the system that turns names like https://www.google.com/search?q=google.com into IP addresses)?

If you can ping an IP address but can't load a website, your internet is fine—your browser or your DNS is the problem.

Actionable Steps for the Modern User

- Check Your DNS: Most people use their ISP's default DNS, which is often slow and logs everything you do. Switch to something like Cloudflare (1.1.1.1) or Google (8.8.8.8) for a faster, more reliable experience.

- Hardwire When It Matters: Wi-Fi is a radio wave subject to interference. If you’re doing something high-stakes—like a job interview or competitive gaming—use an Ethernet cable. It’s the closest you can get to the "pure" internet.

- Audit Your IoT: Since the internet now includes every "smart" device in your home, each one is a potential entry point for hackers. If your lightbulb doesn't need to be on the internet to turn on, maybe don't connect it.

- Understand Data Sovereignty: Data moves across borders. A photo you take in California might be stored in a data center in Virginia and backed up in Dublin. Be aware of the privacy laws governing where your data lives.

The internet is no longer a destination we "go to." We live inside it. It is the invisible fabric of the 21st century. Understanding that it’s a physical, regulated, yet decentralized system of protocols gives you a massive leg up in navigating a world that is increasingly written in code. It’s not just a "definition"; it’s the operating system for humanity.