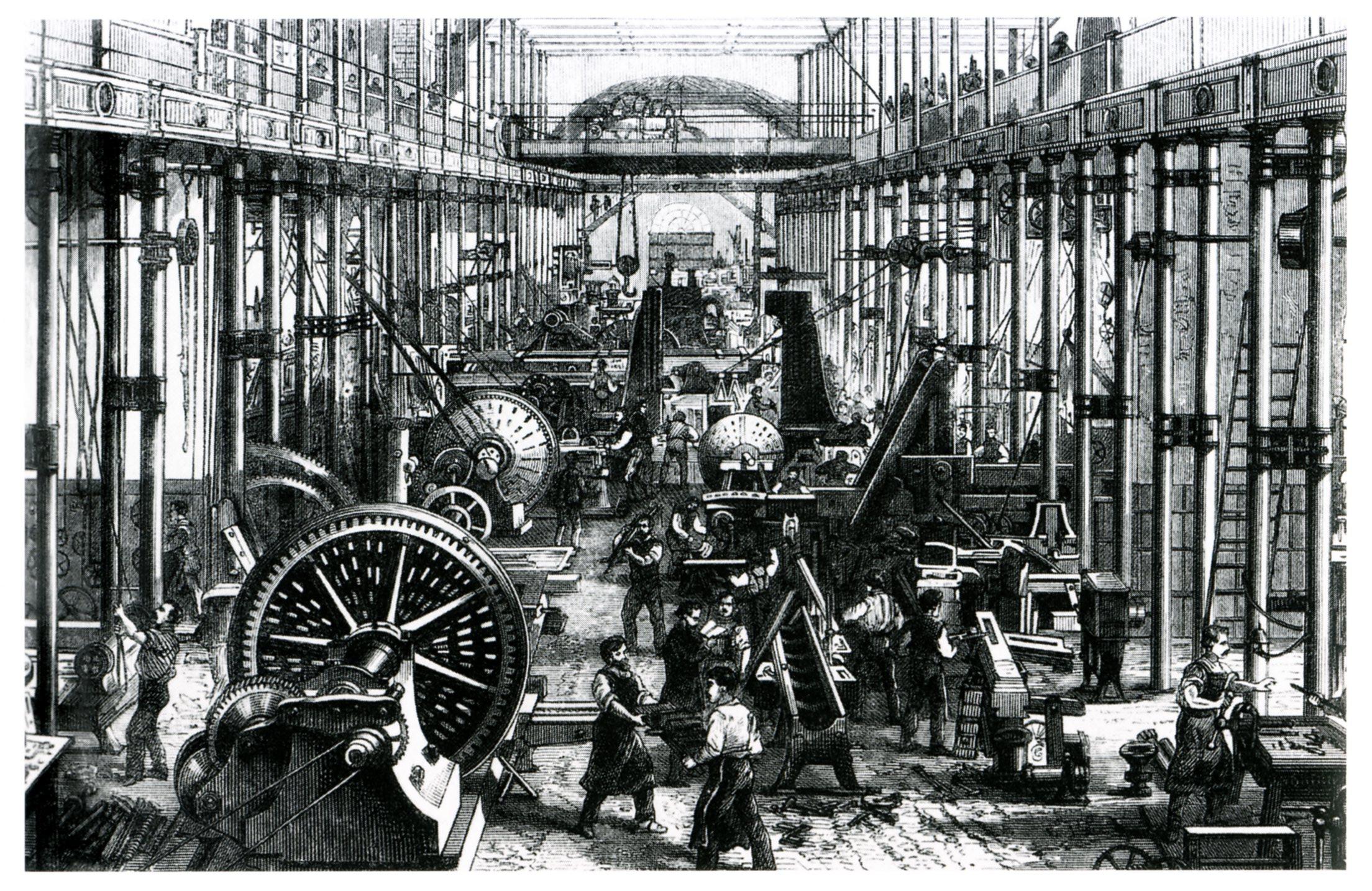

Look around your room. Seriously, just glance at the chair you’re sitting on or the device in your hand. Everything—every single thing—exists because about 250 years ago, a bunch of people in Britain got obsessed with coal and gearboxes. It’s wild. We’re taught in school that the Industrial Revolution was this neat, orderly transition from farms to factories, but it was actually a chaotic, messy, and often accidental explosion of human ingenuity that changed what it means to be alive.

History isn't a straight line.

Before the mid-1700s, if you wanted a shirt, someone’s grandma had to spend hours spinning wool by hand. It was slow. It was expensive. Then, suddenly, James Hargreaves invents the Spinning Jenny in 1764, and suddenly one person can do the work of eight. This wasn't just "business growth." It was a total rupture in the fabric of human society. Honestly, we are still dealing with the fallout of that shift today, from the way our schools are structured like assembly lines to the carbon levels in our atmosphere.

Why Britain? It Wasn't Just Luck

A lot of people think the Industrial Revolution happened in Britain just because they had smart inventors. That's part of it, but it's not the whole story. You’ve got to look at the geography. Britain was basically sitting on a massive pile of "easy" coal. In places like China, coal was buried deep or far from the manufacturing centers, but in the UK, it was right there, practically begging to be dug up.

Economics played a huge role too. Wages in London were higher than almost anywhere else in the world. This created a weirdly perfect incentive: labor was expensive, but energy (coal) was cheap. If you were a business owner, you’d be a fool not to build a machine to replace those expensive workers. In other parts of the world, where labor was dirt cheap, there was zero reason to spend money on a steam engine.

The Steam Engine Obsession

James Watt usually gets all the credit, but he didn't actually "invent" the steam engine. Thomas Newcomen had a clunky version way back in 1712 that was used to pump water out of coal mines. It was incredibly inefficient. Watt’s genius, which he developed while repairing a Newcomen model at the University of Glasgow, was adding a separate condenser.

Think of it like this: Newcomen’s engine was like a car that had to turn its engine off and on at every red light. Watt figured out how to keep the engine running while still getting the work done. This made steam power portable. Suddenly, you didn't need to build your factory next to a fast-moving river for water power. You could put a factory anywhere. You could put it in the middle of a city. And that’s exactly what people did, leading to the massive urban sprawl of Manchester and Birmingham.

🔗 Read more: The Singularity Is Near: Why Ray Kurzweil’s Predictions Still Mess With Our Heads

The Dark Side of the "Dark Satanic Mills"

We can’t talk about the Industrial Revolution without talking about the human cost. It was brutal. Like, actually terrifyingly grim for the people living through it.

The poet William Blake called the new factories "dark Satanic mills," and he wasn't being hyperbolic. Imagine being a ten-year-old kid in 1820. You aren't in school. You’re crawling under a massive, thrumming power loom to clear out lint because your hands are small enough to fit. If you're tired and you slip, you lose a finger. Or worse.

- Working days often lasted 14 to 16 hours.

- The air in cities was so thick with coal soot that it actually changed the evolution of moths (look up the Peppered Moth).

- Cholera and typhoid ran rampant because thousands of people were crammed into "back-to-back" houses with no sewage systems.

There was no "weekend." There were no safety regulations. The wealth being generated was astronomical, but the people actually making the goods—the weavers, the miners, the ironworkers—were barely surviving. This is why we saw the rise of the Luddites. People often use "Luddite" today to mean someone who is bad with iPhones, but the original Luddites were skilled weavers who smashed power looms because the machines were destroying their livelihoods and their communities. They weren't anti-technology; they were anti-poverty.

The Second Wave: Electricity and Steel

If the first phase was about coal and cotton, the second Industrial Revolution (roughly 1870 to 1914) was about chemistry, electricity, and steel. This is where things get really recognizable to us.

The Bessemer process made steel cheap. Before this, steel was a luxury. Once you could mass-produce it, you got skyscrapers, massive suspension bridges, and thousands of miles of railroad tracks. Then came Michael Faraday and Nikola Tesla. Electricity changed the literal rhythm of human life. For the first time in history, "night" became optional. Factories could run 24/7.

This period also birthed the modern corporation. Think of names like Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Ford. They didn't just make products; they created systems. Henry Ford’s assembly line in 1913 didn't just make the Model T affordable; it turned the human worker into a specialized part of a machine. It was efficient. It was profitable. It was also incredibly boring for the workers, leading to high turnover rates that Ford eventually solved by doubling wages to five dollars a day—a move that basically jump-started the American middle class.

💡 You might also like: Apple Lightning Cable to USB C: Why It Is Still Kicking and Which One You Actually Need

Global Impact and Modern Echoes

The Industrial Revolution wasn't just a European or American event. It reshaped the entire planet, often through the lens of colonialism. European powers needed raw materials—rubber from the Congo, cotton from India and Egypt, tin from Southeast Asia. This drive for resources fueled empires and created global trade networks that still dictate how we move goods today.

It's also where our climate crisis started.

Scientists like Eunice Newton Foote (who was ignored for a long time) and John Tyndall began realizing in the mid-19th century that certain gases in the atmosphere could trap heat. We can trace the hockey-stick graph of global CO2 levels right back to the moment Watt’s steam engines started proliferating. It’s a strange paradox: the very machines that lifted billions of people out of extreme poverty and gave us modern medicine are the same ones that put our biosphere at risk.

Common Misconceptions

People think the revolution happened overnight. It didn't. It was a slow burn. In many parts of England in the 1830s, you would still see people using hand tools alongside massive steam factories.

Another big myth is that it made everyone poorer. In the short term, for the working class, it definitely made life more dangerous and miserable. But in the long term, looking at the data, the Industrial Revolution eventually led to a massive rise in living standards. Literacy rates skyrocketed. Life expectancy, which had been stagnant for centuries, began its steady climb. It was a high-price entry fee for the modern world.

How to Apply This History Today

Understanding the Industrial Revolution isn't just for history buffs. It's a blueprint for how we handle the "AI Revolution" happening right now.

📖 Related: iPhone 16 Pro Natural Titanium: What the Reviewers Missed About This Finish

Watch the Displacement Cycles

Just as power looms replaced hand weavers, AI is shifting the landscape for knowledge workers. The lesson from the 1800s is that while new jobs are created, the transition is painful. If you're in a field being automated, the "Luddite" response is natural, but the long-term winners are usually those who learn to operate the new "engines."

Energy is Everything

The 18th century was defined by the shift from wood to coal. Our current era is defined by the shift from fossil fuels to renewables. History shows that the society that masters the cheapest, most abundant energy source becomes the global leader.

Regulation Always Lags

It took decades for the British Parliament to pass the Factory Acts to protect children. Technology always moves faster than law. Expect the same delay with modern issues like data privacy or AI ethics.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Primary Source Check: Read "The Condition of the Working Class in England" by Friedrich Engels. He was there. He saw the slums firsthand. It’s a gut-punch of a read that counters the "clean" version of history.

- Visit History: If you're ever in Manchester, UK, go to the Science and Industry Museum. Seeing a 19th-century steam engine actually running is a visceral experience. The noise alone is life-changing.

- Track the Carbon: Look at the Keeling Curve data. It’s a direct visual link between the start of the Industrial Revolution and our current atmospheric reality.

- Analyze Your Work: Identify one task in your daily life that would have been impossible in 1750. Think about the chain of inventions required to make that one task happen. It’s a great exercise in gratitude and perspective.

The transition wasn't "inevitable." It was a series of choices, some brilliant and some horrific. We are currently living in the "Next Industrial Revolution," and the way we manage the balance between profit and human well-being will determine if the history books of 2200 look back on us as pioneers or as a cautionary tale.