You probably don’t think about sulphuric acid when you’re scrolling through your phone or eating a sandwich. But honestly, you should. It is the silent engine of modern civilization. It’s so vital that economists actually use its consumption levels to measure a nation’s industrial health. If a country is making a lot of this stuff, they’re usually booming. But how is sulphuric acid formed in the first place? It doesn't just bubble up from the ground in a ready-to-use state, despite what you might see in some sci-fi movies.

It’s a multi-step chemical dance. A high-stakes one.

The Raw Materials: Where the Magic Starts

Before we get into the heavy chemistry, we need the basics. Most of the world’s sulphuric acid starts with elemental sulphur. You know the stuff—bright yellow, smells faintly of matches, and often found as a byproduct of natural gas and oil refining. In the old days, people used to mine it from volcanic deposits, but today, we’re mostly stripping it out of fossil fuels to keep our air cleaner.

Sometimes, we use metal ores instead. If you’ve ever heard of "smelting" copper or lead, those processes release sulphur dioxide gas. Instead of letting that gas float away and cause acid rain, clever engineers catch it and turn it into acid. It’s basically the ultimate recycling project. You also need oxygen (plenty of that in the air) and water. Simple, right? Well, not exactly.

The Contact Process: The Gold Standard

Nearly all modern production happens via the Contact Process. This method replaced the old, clunky "Lead Chamber Process" because it’s way more efficient and produces much higher purity.

Step 1: Making the Gas

First, we burn the sulphur. We spray molten sulphur into a furnace and blast it with dry air. The result is sulphur dioxide ($SO_2$).

$$S(s) + O_2(g) \rightarrow SO_2(g)$$

📖 Related: Why the CH 46E Sea Knight Helicopter Refused to Quit

This reaction generates a massive amount of heat. If you were standing near a commercial burner, you'd feel the power. This isn't just a gentle flame; it's an industrial inferno.

Step 2: The Tricky Part (The Catalyst)

Here is where things get complicated. We need to turn that $SO_2$ into sulphur trioxide ($SO_3$). This doesn't happen easily. If you just leave $SO_2$ and oxygen together, they kind of just sit there staring at each other. They need a nudge.

We use a catalyst, usually Vanadium Pentoxide ($V_2O_5$). The gas mixture is passed over beds of this catalyst at temperatures around 450°C.

$$2SO_2(g) + O_2(g) \rightleftharpoons 2SO_3(g)$$

This is a reversible reaction. It’s a literal balancing act. According to Le Chatelier's Principle—a name that brings back nightmares for chemistry students—we have to keep the conditions "just right." Too hot, and the reaction goes backward. Too cold, and it's too slow to be profitable. Most plants use multiple "stages" or beds of catalyst to squeeze out every last bit of conversion, often hitting 99.5% efficiency.

Step 3: Why You Can’t Just Add Water

Now, logic would suggest that you just take your $SO_3$ gas, bubble it through water, and boom—sulphuric acid ($H_2SO_4$).

👉 See also: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

Don't do that.

If you add $SO_3$ directly to water, it creates a violent, uncontrollable mist of sulphuric acid droplets that is almost impossible to condense. It’s a safety nightmare and an engineering disaster. Instead, they dissolve the $SO_3$ into existing concentrated sulphuric acid. This creates a thick, oily liquid called Oleum ($H_2S_2O_7$).

$$H_2SO_4(l) + SO_3(g) \rightarrow H_2S_2O_7(l)$$

Once you have the Oleum, you can safely mix it with water to get the exact concentration of acid you need. It’s a roundabout way of doing things, but it’s the only way to stay safe and efficient.

Why Does This Even Matter to You?

You’re likely not planning on building a chemical plant in your backyard. But understanding how is sulphuric acid formed helps you understand the price of your groceries.

The biggest consumer of sulphuric acid is the fertilizer industry. To get phosphorus out of phosphate rock so plants can actually eat it, you have to douse the rock in sulphuric acid. No acid, no high-yield crops. No high-yield crops, and the global food supply chain collapses.

✨ Don't miss: Starliner and Beyond: What Really Happens When Astronauts Get Trapped in Space

- Lead-Acid Batteries: Your car's starter battery is literally full of this stuff.

- Metal Processing: Cleaning steel (pickling) before it gets used in buildings.

- Detergents: Many of the surfactants that make your soap foamy start with a sulphuric acid reaction.

- Paper: It's used in the pulping process.

Misconceptions and Safety

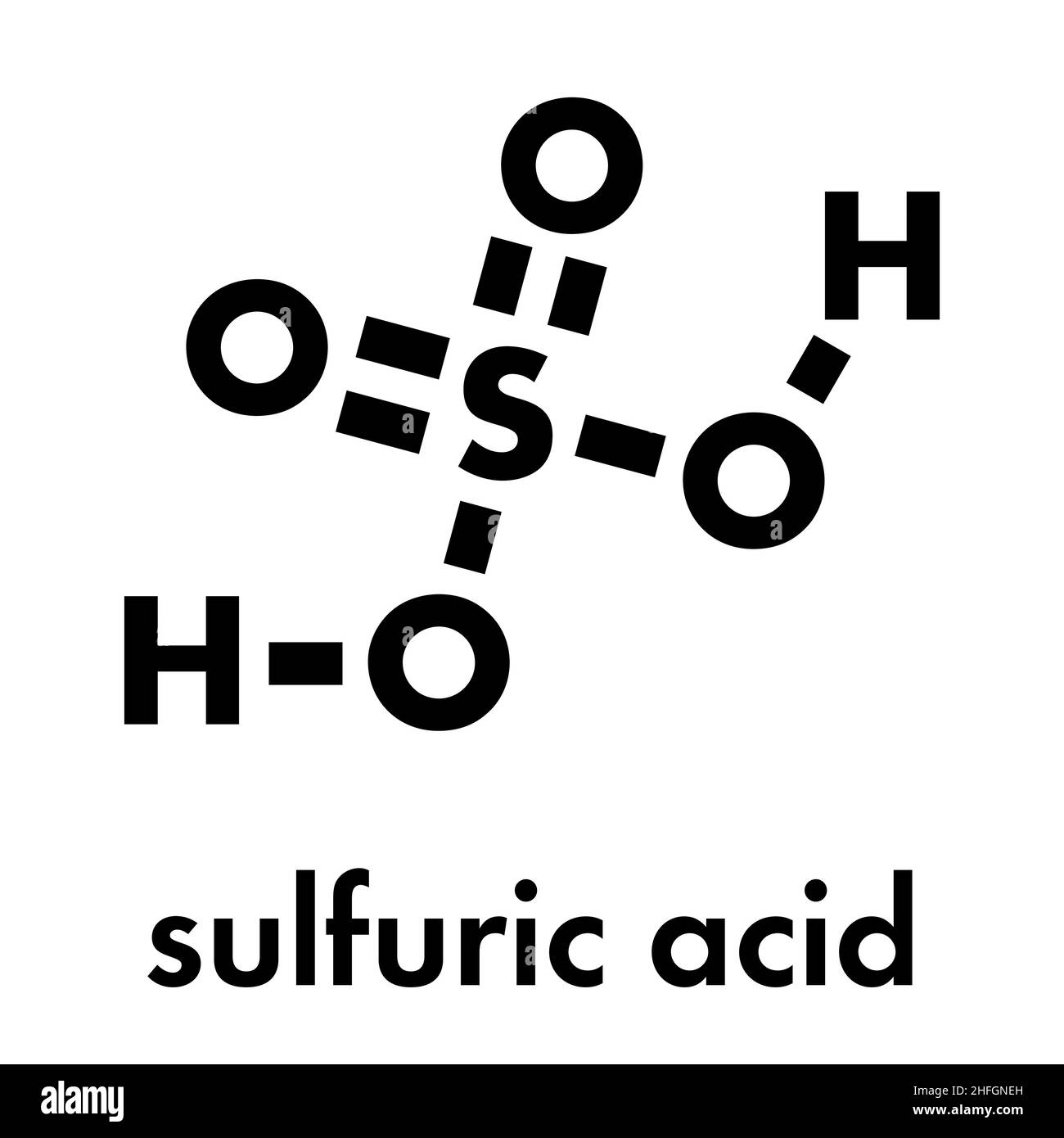

People often think sulphuric acid is the "strongest" acid. It’s definitely powerful and can cause horrific chemical burns because it’s a "dehydrating agent"—it literally rips the water molecules out of sugar, wood, or skin, leaving behind charred carbon. But in the world of chemistry, there are "superacids" like fluoroantimonic acid that make sulphuric acid look like lemon juice.

Another weird thing? Pure sulphuric acid doesn't actually corrode iron very well. It forms a "passive" layer on the metal. It’s only when you dilute it with water that it starts eating through pipes like a hungry monster. This is why industrial plants have to be incredibly careful about moisture getting into their storage tanks.

Environmental Impact: The Double-Edged Sword

We can't talk about how is sulphuric acid formed without mentioning the environment. In the mid-20th century, $SO_2$ emissions from coal plants and smelters led to devastating acid rain. It killed forests and turned lakes into vinegar.

The good news? Modern technology has flipped the script. Most sulphuric acid today is produced by "scrubbing" those emissions. By forcing ourselves to make the acid, we've actually cleaned up the air significantly. According to the EPA, sulphur dioxide concentrations in the US have dropped by over 90% since the 1980s. The acid is now a byproduct of environmental protection.

Looking Ahead: The "Sulphur Crisis"?

Ironically, as we move away from fossil fuels, some experts, like Professor Mark Maslin from University College London, worry we might actually run into a sulphur shortage. Since we get most of our sulphur from oil and gas refining, a green energy transition means less "easy" sulphur.

We might have to go back to mining it directly, which is energy-intensive and environmentally messy. It’s a classic example of how solving one problem (climate change) can create a weird ripple effect in a completely different industry (chemical manufacturing).

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you're interested in the chemistry or the business of industrial acids, here is what you should keep an eye on:

- Monitor Fertilizer Stocks: Since 60% of sulphuric acid goes to agriculture, the price of the acid is a leading indicator for global food prices.

- Safety First: If you ever handle battery acid at home, always remember the rule: "Add Acid to Water, like you oughter." Never pour water into concentrated acid, or it might splash back into your face due to the intense heat of the reaction.

- Watch the Energy Transition: Keep an eye on "green" mining tech. Companies are looking for ways to extract sulphur from sea salt or deep underground deposits without the massive carbon footprint.

Understanding the formation of this "King of Chemicals" isn't just a school science project—it's a look under the hood of how the modern world actually functions. From the catalyst beds of the Contact Process to the battery in your garage, sulphuric acid is the invisible thread holding it all together.