You’ve probably never heard her name in a doctor's office, but Henrietta Lacks is basically the reason you’re alive today. If you’ve had a COVID-19 vaccine, been treated for cancer, or even just taken a simple ibuprofen, you are connected to her. It’s wild. Most of modern medicine rests on the shoulders of a woman who never gave permission for her body to be used this way.

She was a Black tobacco farmer from Virginia, a mother of five, and she died at the young age of 31 from a brutal case of cervical cancer. But parts of her didn't die. Her cells, known globally as HeLa, became the first human cell line to survive and thrive in a laboratory. They didn't just survive; they were unstoppable. They grew at a rate that baffled scientists in 1951.

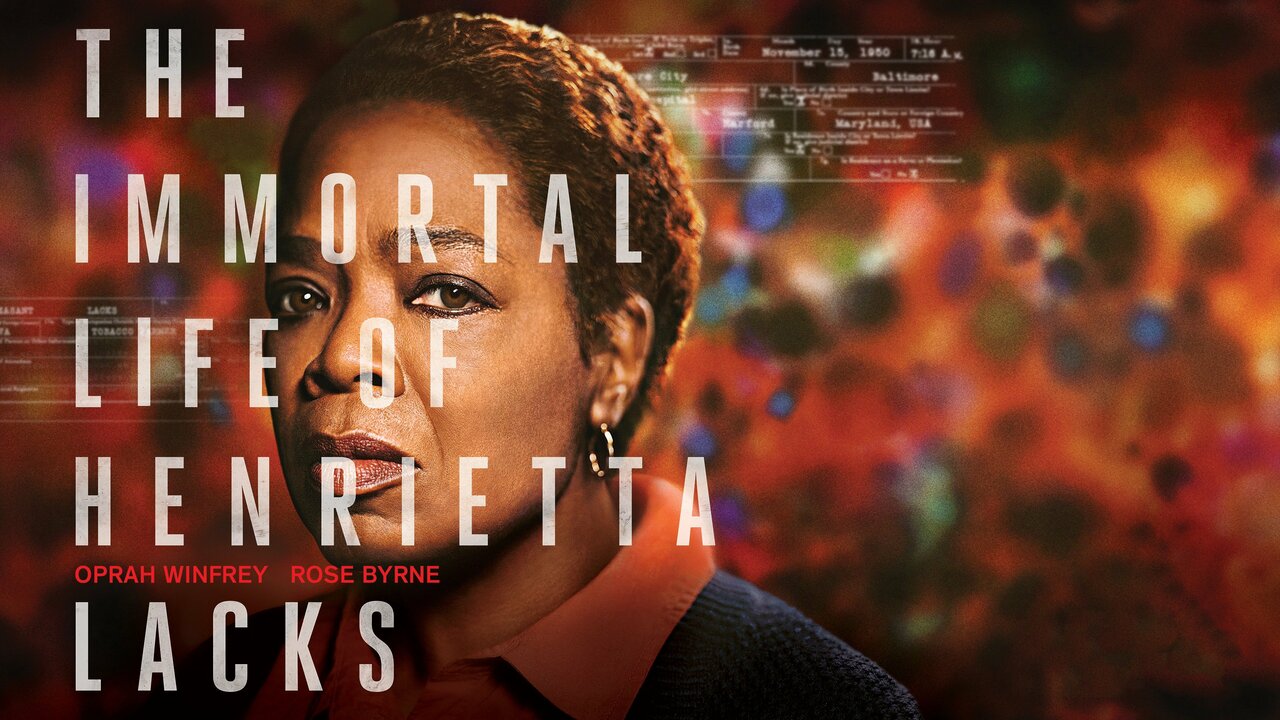

The story of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks isn't just a science textbook entry. Honestly, it’s a story about race, poverty, and the massive ethical gaps in how we treat human beings in the name of "progress." It’s complicated. It’s messy. And it is still happening.

What actually happened at Johns Hopkins?

In early 1951, Henrietta walked into the Johns Hopkins Hospital—one of the few hospitals at the time that treated Black patients—complaining of a "knot" in her womb. She had cervical cancer. During her treatment, a surgeon named Dr. Lawrence Wharton Jr. snipped two small samples from her cervix without telling her. One was healthy tissue; the other was the tumor.

He gave them to Dr. George Gey.

Gey had been trying for decades to grow human cells in a lab. Usually, they just died. But Henrietta’s cells were different. They doubled every 24 hours. They were robust. Gey started mailing them to researchers all over the world in literal padded envelopes. He didn't do it for money, but he did it without Henrietta’s consent.

While Henrietta was suffering through excruciating radium treatments that charred her skin, her cells were becoming the most valuable biological tool on Earth. She died on October 4, 1951. Her family had no idea her "immortal" cells were being sold, packaged, and used in thousands of experiments. They didn't find out for twenty years. Imagine finding out your mother is technically "alive" in a vial in London or Tokyo while you're struggling to pay for your own health insurance. That’s the reality the Lacks family faced.

The HeLa explosion and the polio breakthrough

It is hard to overstate how much we owe to HeLa. Before these cells, scientists couldn't reliably test how a virus interacted with human cells without, well, using a human.

👉 See also: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

When the polio epidemic was paralyzing thousands of children, Jonas Salk needed a way to test his vaccine. HeLa cells were the answer. They were used to mass-produce the virus so the vaccine could be refined. It worked. Without Henrietta, the polio vaccine might have taken years longer.

But it didn't stop there. HeLa cells have been to space to see what zero gravity does to human tissue. They were used to develop the HPV vaccine, which now prevents the very cancer that killed Henrietta. They helped map the human genome. They’ve been used to study leukemia, Parkinson’s, and even the effects of atomic radiation.

Estimates suggest that if you gathered all the HeLa cells ever grown, they would weigh more than 50 million metric tons. That is a staggering amount of life from one woman who died over 70 years ago.

Why the ethics are still a mess

We like to think that "informed consent" is a permanent fixture of medicine. It isn't. In the 1950s, it basically didn't exist, especially for Black patients in Jim Crow-era hospitals.

The Lacks family has spent decades fighting for recognition and some semblance of control over Henrietta’s genetic legacy. For a long time, researchers published Henrietta’s real name and her medical records without permission. In 2013, researchers in Germany even published the full HeLa genome sequence online. The family was blindsided. They felt like their mother’s privacy was being violated all over again, right down to her DNA.

Eventually, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reached an agreement with the family. Now, two family members sit on a committee that reviews applications to use the HeLa genome data. It’s a start. But it doesn't change the fact that billions of dollars have been made off HeLa cells by biotech companies while many of Henrietta’s descendants couldn't afford a check-up.

Correcting the record: Common misconceptions

People often get a few things wrong about this story.

✨ Don't miss: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

First, George Gey didn't "steal" the cells to get rich. He actually gave them away for free initially. The commercialization happened later when specialized companies started mass-producing them.

Second, Henrietta wasn't chosen because she was Black; she was chosen because she was a patient at a hospital where research was happening. However, the lack of communication and the disregard for her family were deeply rooted in the systemic racism of the era. Black bodies were often treated as medical resources rather than people with rights.

Third, HeLa cells aren't "magic." They are cancer cells. They have 82 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. This genetic instability is actually what makes them so hardy, but it also means they aren't "normal" human cells. They are a mutation that happened to be perfect for laboratory work.

The legacy of Rebecca Skloot’s work

Most of us only know this story because of Rebecca Skloot. Her book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, took over a decade to write. She worked closely with Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah Lacks, who was desperate to know who her mother really was.

The book changed everything. It moved the conversation from "the HeLa cell line" to "Henrietta Lacks, the person." It’s the difference between a tool and a human being.

Recent legal victories

In 2023, the Lacks family reached a landmark settlement with Thermo Fisher Scientific. The family had sued, arguing that the company was "unjustly enriching" itself by mass-producing and selling HeLa cells without the family's permission or compensation.

This was a massive deal. It sets a precedent. It says that even if something happened decades ago, companies still have a responsibility to address the exploitation of human tissue.

🔗 Read more: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

How to honor Henrietta Lacks today

If you want to actually do something with this information rather than just feeling bad about it, there are real ways to engage with the legacy of bioethics.

Educate yourself on patient rights.

In the U.S., the "Common Rule" governs how human subjects are treated in research. It was recently updated, but there are still debates about whether "de-identified" tissue (like a mole removed at the dermatologist) should require consent for future research. Stay informed.

Support the Henrietta Lacks Foundation.

Rebecca Skloot started a foundation that provides grants for the descendants of people who were used in research without their consent. It’s a way to provide the education and healthcare that Henrietta’s own family was denied for so long.

Ask questions.

When you sign those long forms at the doctor, ask what happens to your samples. Most of the time, they are incinerated. Sometimes, they are used for teaching or research. You have the right to know.

Henrietta Lacks changed the world. She didn't choose to, but she did. The least we can do is remember her name and ensure that the "immortal" part of her story is handled with the dignity she was denied in life.

To truly understand the impact, you have to look at your own medicine cabinet. Most of those treatments exist because of a woman who loved to dance, wore red nail polish, and unknowingly gave her life to science. We are all living in a world built by HeLa.

Moving forward with Henrietta's legacy

The best way to respect Henrietta's contribution is to demand transparency in medicine. Healthcare should be a partnership between patient and provider, not a one-way street where the patient is a "specimen."

- Review your local hospital's policy on tissue research.

- Read the 2018 updates to the Common Rule regarding informed consent.

- Engage with community health initiatives that focus on closing the trust gap between marginalized groups and medical institutions.

By advocating for ethical standards today, you help ensure that Henrietta's story—one of both incredible scientific gain and profound personal loss—is never repeated in the shadows.