You ever get that weird feeling when you step out of a subway station and for a split second, you have absolutely no idea which way is north? Your brain is scrambling. It’s looking for a landmark, a specific curve in the road, or maybe that one giant neon sign you remember from last time. That mental scramble is exactly what Kevin Lynch was obsessed with. Back in 1960, he published The Image of the City by Kevin Lynch, and honestly, it changed how we think about urban life forever.

He didn't just look at maps. He looked at people.

Lynch wanted to know why some cities feel like a warm hug—easy to navigate and familiar—while others feel like a hostile maze designed to make you lose your mind. He interviewed residents in Boston, Jersey City, and Los Angeles, asking them to draw "mental maps" from memory. What he found wasn't just about architecture; it was about psychology. He realized that we all build a "legible" version of our surroundings in our heads. If a city is legible, you feel safe and in control. If it's a mess, you feel anxious.

The Five Elements That Live in Your Head

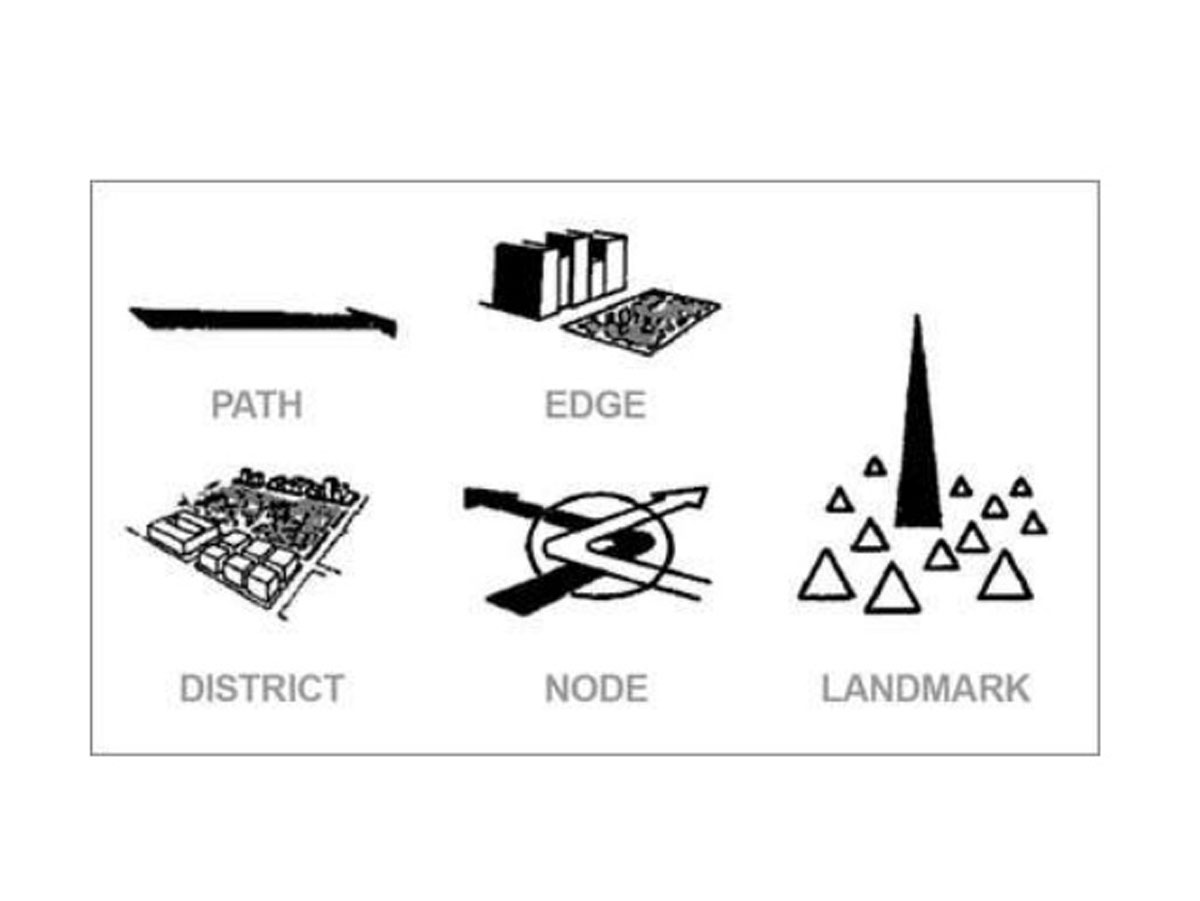

Most people think of a city as a collection of buildings. Lynch argued it’s actually a collection of five specific elements. He didn't just invent these for a textbook; he observed them in the way people actually described their commute or their childhood neighborhood.

First, you've got Paths. These are the channels you move through. Streets, walkways, transit lines, canals. For most people, paths are the dominant feature of their mental map. If you think of New York, you probably think of Broadway or the High Line. If those paths are clear, the city makes sense.

Then there are Edges. These are the boundaries. They aren't necessarily paths, but they are the "breaks" in continuity. Think of a waterfront, a giant wall, or a railroad cut. In Chicago, Lake Michigan is the ultimate edge. It’s the literal end of the world for that city’s grid. Edges can be intimidating, but they also provide a massive sense of orientation.

Districts and Nodes

Districts are the medium-to-large sections of the city that have some kind of common character. You know when you’ve entered one. You can feel it. The North End in Boston or the French Quarter in New Orleans. You’re "inside" them. Lynch found that people use these districts to organize the chaos of a metropolis into digestible chunks.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Nodes are the strategic spots. They are the junctions or concentrations where paths meet. Think of Times Square or Piccadilly Circus. They are the "breaks" in transport where you shift from one mode to another. A node is a place you enter, and it's usually a high-intensity point on your internal map.

Finally, we have Landmarks. These are the external reference points. You don't enter them; you just see them. A tower, a mountain, a specific golden arches sign that’s been there for forty years. They are the simplest way to stay oriented. "Turn left at the giant church" is the most human way to give directions, and Lynch knew it.

Why Jersey City Failed the Test

In his research for The Image of the City by Kevin Lynch, Lynch famously compared Boston to Jersey City. Boston, despite its confusing cow-path streets, had a strong "imageability." People could identify the Common or the Charles River. They had a sense of place.

Jersey City, at the time, was a different story. Lynch described it as a place where people struggled to form a coherent mental map. It was a fragmented landscape of railroads, highways, and disconnected neighborhoods. Because it lacked strong nodes and clear landmarks, residents felt a sense of "placelessness." It’s a harsh critique, but it highlights a fundamental truth: if you can’t map a place in your head, you can’t truly belong there.

This isn't just academic fluff. It affects your stress levels. When a city lacks legibility, your brain has to work harder just to exist. You're constantly scanning, constantly unsure. That "low-key anxiety" you feel in a sprawling suburb or a poorly planned industrial zone? That’s exactly what Lynch was talking about.

The Concept of Imageability

Lynch coined this term "imageability," which basically means how easy it is for a physical object to trigger a sharp, intense image in the mind of an observer. A highly imageable city is "legible." It can be read like a book.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

Think about Florence. The Duomo is visible from almost everywhere. It’s a massive landmark that anchors the entire city. You always know where you are in relation to it. That’s high imageability. Now think about a generic office park in the suburbs of any major US city. Every building looks the same. The "paths" are just winding roads with no distinct features. The "nodes" are just parking lots. It has zero imageability. You’re lost the second you turn off your GPS.

How Modern Urban Planning Uses This

You’d be surprised how much of your daily life is influenced by a book written over sixty years ago. Modern urban designers use Lynch’s framework every time they plan a new park or a transit hub.

- Wayfinding systems: Those big maps in malls or downtown areas? They are designed specifically using nodes and landmarks to help you build a mental map.

- Zoning laws: When cities protect "historic districts," they are preserving the "district" element Lynch identified as crucial for identity.

- Skyline protection: Cities like London or Vancouver protect "view corridors" to ensure landmarks remain visible, maintaining the city's imageability.

But it’s not just about aesthetics. It’s about social equity. Lynch argued that a clear city image is a basic human need. If people can’t navigate their own city, they are effectively shut out of it. They won't explore new neighborhoods, they won't use public transit, and they won't feel a sense of ownership over their environment.

The Flaws and Criticisms

Okay, look, Lynch wasn't a god. He had blind spots. One of the biggest critiques of The Image of the City by Kevin Lynch is that it’s very visual-heavy. It ignores how a city smells, how it sounds, or how it feels under your feet.

A blind person's mental map of a city is incredibly rich, but it doesn't rely on landmarks or edges in the way Lynch described. It relies on the sound of a specific vent, the slope of a sidewalk, or the smell of a bakery. By focusing so much on the visual, Lynch narrowed the scope of what a city "image" could be.

There’s also the issue of technology. We live in the age of Google Maps. Does "imageability" even matter if a blue dot on a screen tells you exactly where to turn? Some argue that we are losing our ability to form mental maps because we don't have to anymore. We are becoming "geographically illiterate." But even with a phone in your hand, you still experience that feeling of "place." You still know when a neighborhood feels right and when it feels wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Practical Ways to "Map" Your Own World

If you want to actually use Lynch’s ideas to improve your life, stop looking at your phone for ten minutes. Next time you're in a new neighborhood, try to identify one landmark, one edge, and one node.

- Find your anchor: Identify one massive building or natural feature. Use it to orient yourself.

- Learn the boundaries: Where does the neighborhood change? Is it a highway? A park? A river? Recognizing the edges makes the space feel contained and understandable.

- Trace the paths: Don't just follow the GPS. Notice the character of the street. Are there trees? What color are the bricks?

- Identify the "heart": Find the node—the place where everything happens. It’s usually a plaza, a busy intersection, or a station.

By consciously looking for these five elements, you start to inhabit a space rather than just passing through it. You build a "legible" world.

Kevin Lynch didn't just write a book about architecture; he wrote a book about how we perceive our place in the world. He proved that the city isn't just steel and stone. It's a living, breathing image that exists inside our minds. Whether you’re a professional planner or just someone trying to find a decent coffee shop, understanding your mental map is the first step toward truly feeling at home.

Actionable Insights for Navigating and Understanding Your City

To apply Lynch’s theories to your own urban experience or professional projects, focus on these specific steps:

- Audit Your Neighborhood: Walk your local area and try to sketch a map from memory. Notice what you leave out—those "blind spots" are often areas that lack clear nodes or landmarks.

- Enhance Legibility: If you are a business owner or developer, create "landmarks" (unique signage, art, or lighting) to help people orient themselves near your location.

- Support Distinct Districts: Advocate for local planning that maintains the unique character of neighborhoods. Homogenized development destroys the "district" element that makes cities navigable.

- Prioritize Paths: When choosing a place to live or work, look at the quality of the "paths." Are they inviting and clear, or are they confusing and utilitarian? High-quality paths lead to a more satisfied urban life.

Understanding the "image of the city" isn't just for academics; it's a tool for anyone who wants to feel more connected to the world around them.