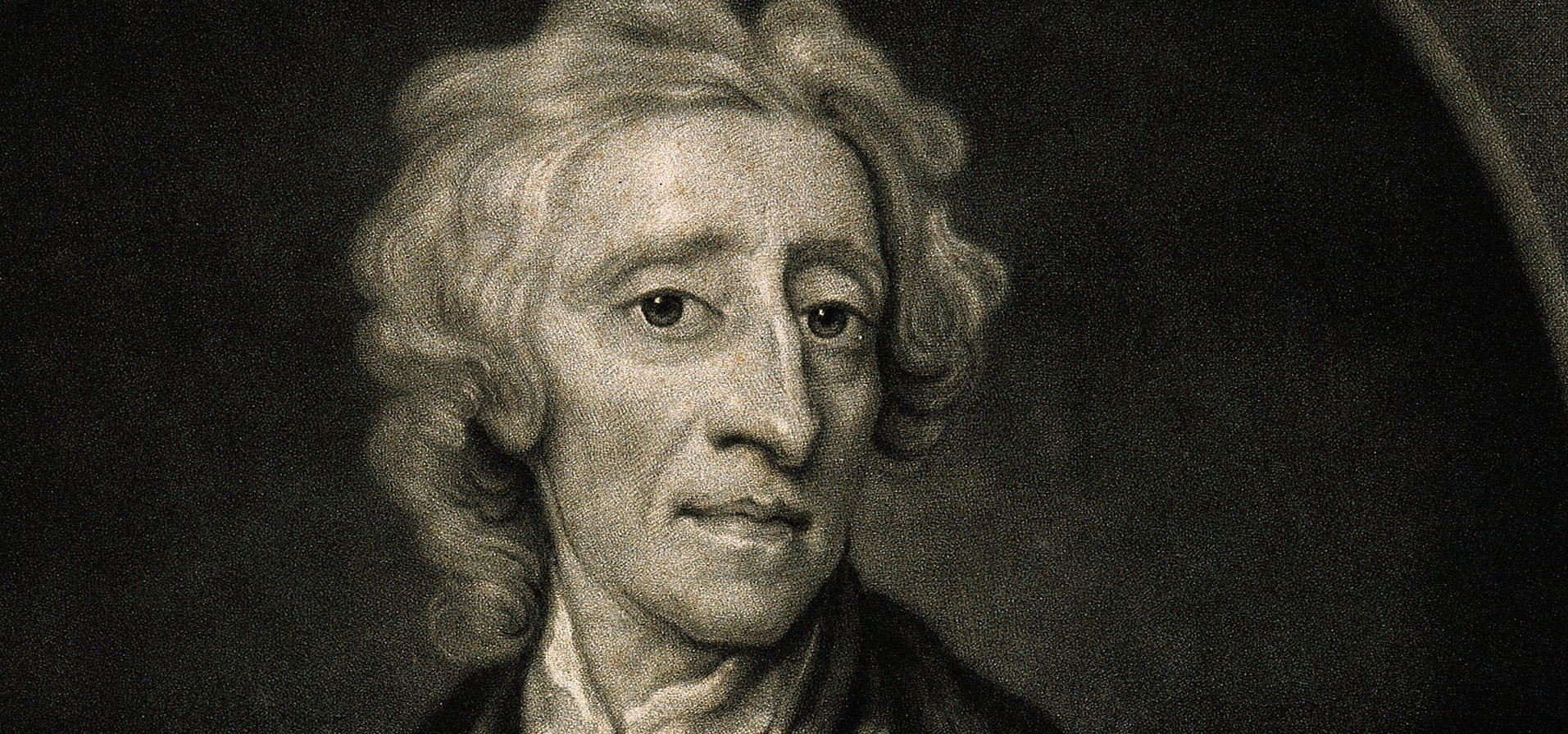

You’ve seen him. Honestly, even if you don't recognize the name immediately, you’ve definitely seen that long, gaunt face staring back at you from a dusty history textbook or a "Founding Fathers" documentary. He’s the guy with the high forehead, the slightly oversized nose, and that intense, piercing gaze that seems to be judging your lack of civic engagement.

That image of John Locke is everywhere. It’s the visual shorthand for the Enlightenment.

But here’s the thing: most of us treat that face like a static icon, a logo for "Liberty™," without ever wondering who actually sat in the chair or what he was trying to say with his clothes. Locke wasn't just a brain in a jar writing about "Life, Liberty, and Property." He was a real person living through the chaos of 17th-century England—an era of plague, fire, and literal revolution. When you look at his most famous portraits, you aren't just seeing a philosopher; you're seeing a carefully constructed persona designed to survive a very dangerous time.

The Kneller Portrait: More Than Just a Headshot

If you Google the man, the first result is almost always the 1697 portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller.

This is the definitive image of John Locke. Kneller was basically the Annie Leibovitz of the late 17th century. If you were anyone in the British elite, you got a Kneller. But look closer at how Locke is dressed. He isn't wearing the stiff, formal robes of a high-ranking judge or the elaborate wig of a courtier.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

He’s wearing what looks like a bathrobe.

Seriously, it’s a loose, brown "banyan" or wrapping gown, paired with an open-necked white shirt. In the 1690s, this was the "tech bro hoodie" of the intellectual set. It signaled "I’m a man of leisure and thought, too busy pondering the nature of the human soul to bother with a cravat." It was a deliberate choice. Locke wanted to be seen as a private citizen, a philosopher of the people, rather than a servant of the crown.

This specific painting now hangs in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. Why Russia? Because Catherine the Great was a huge fan. She bought it from the collection of Sir Robert Walpole in 1779. It’s kind of wild to think that the face of Western liberalism spent centuries tucked away in the heart of the Russian Empire.

The Face That Launched a Thousand Constitutions

While the Kneller portrait is the "official" version, there are other versions that tell a different story.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

- The Brounower Sketch: Sylvester Brounower was Locke’s secretary and servant. He lived with Locke during his exile in the Netherlands. His sketches of Locke are much more intimate and less "glossy." They show a man who looks tired, perhaps a bit sickly (Locke suffered from chronic asthma his whole life).

- The Jefferson Copy: Thomas Jefferson was so obsessed with Locke that he commissioned a copy of the Kneller portrait. He hung it at Monticello alongside Francis Bacon and Isaac Newton. To Jefferson, these three were the "trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced."

- Modern Reinterpretations: In 2024 and 2025, scholars like Joachim Möller have been digging into how Locke’s image influenced 18th-century art beyond just portraiture. His theories on how we perceive light and color—found in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding—actually changed how painters like John Constable approached the canvas.

Why the Image of John Locke Still Matters in 2026

We live in a world of deepfakes and AI-generated avatars. In that context, the image of John Locke serves as a weirdly grounding anchor.

People use his face on social media to argue about property rights or vaccine mandates or the "social contract." Usually, they’re using the Kneller version. It’s become a meme-ified symbol of "Reason." But if you actually read his work, you realize Locke would probably be horrified by how we use his image today as a shortcut for complex arguments.

Locke’s whole philosophy was based on the tabula rasa—the idea that we are born as blank slates. Everything we are comes from experience. In a way, his portraits are the physical record of his own experiences. The sunken cheeks tell the story of a man who spent years in hiding because his ideas were considered treasonous. The simple clothes reflect a man who valued the "plain style" of truth over the gaudy lies of the Stuart court.

How to Spot a "Real" Locke

If you’re ever in a museum and think you’ve spotted him, look for these specific features:

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

- The Nose: It’s prominent. Very prominent.

- The Hair: By the time he was famous, Locke’s hair was thin and grey. He often wore it long to his shoulders rather than wearing the massive, towering wigs popular at the time.

- The Gaze: He rarely looks "happy." He looks inquisitive. Like he’s waiting for you to define your terms.

Beyond the Canvas: The Visual Legacy

It’s not just about oil paintings. Locke’s visual footprint extends into the very architecture of our democracy. When you look at the U.S. Declaration of Independence, you are looking at a document that is, visually and textually, a "portrait" of Lockean thought.

The way we "see" liberty is shaped by the way Locke was seen.

But we have to be careful. As scholars like Jeremy Waldron have pointed out, Locke was a man of contradictions. He wrote about equality but held investments in the slave trade through the Royal African Company. He advocated for religious tolerance but excluded Catholics and atheists. When we look at that calm, scholarly image of John Locke, we are looking at a man who was deeply "of his time," even as he tried to write for all time.

Take Action: Where to See Him Yourself

If you want to move beyond the screen and see the "real" Locke, here are your best bets:

- National Portrait Gallery (London): They hold several versions, including the one by Brounower. It’s the best place to see the human side of the philosopher.

- The Hermitage (St. Petersburg): For the definitive Kneller masterpiece (if you can get there).

- Monticello (Virginia): To see the version that inspired the American Revolution.

The next time you see that face pop up in your feed or a book, don't just scroll past. Look at the eyes. Consider the bathrobe. Remember that behind the "image of John Locke" was a guy who was just trying to figure out how humans can live together without killing each other. We're still trying to solve that one.

Next Step: To get a deeper sense of the man behind the paint, look up "John Locke’s 1697 letter to William Molyneux." He talks specifically about his health and his reluctance to sit for portraits, giving you a much more personal view than any oil painting ever could.