March 15th. It’s just another Tuesday or Thursday on the calendar for most people, yet there is this lingering sense of dread that comes with it. You’ve probably heard the phrase "Beware the Ides of March" tossed around in movies or English class. It sounds like a mystical curse. In reality, it was just a deadline for settling debts in ancient Rome.

Then came the year 44 BCE.

Suddenly, a routine day for paying bills turned into the most famous political assassination in human history. Julius Caesar, a man who had essentially "won" Rome, walked into a meeting and never walked out. But the story we tell ourselves today—the one with the dramatic "Et tu, Brute?" and the soaring speeches—is mostly a mix of William Shakespeare’s theater and Roman propaganda. If you want to understand why the Ides of March still matters in 2026, you have to look past the velvet curtains of the Globe Theatre.

The Ides of March Wasn't Originally About Death

Before the daggers came out, the "Ides" was just a marker. The Romans didn't number their days 1 through 31 like we do. They used three main landmarks: the Kalends (the 1st), the Nones (usually the 5th or 7th), and the Ides. The Ides generally fell on the 13th, except in March, May, July, and October, when it fell on the 15th.

It was a day for the moon. Full moons, specifically.

Romans used this day to honor Jupiter, their supreme deity. They’d lead a sheep through the streets of Rome to the Capitoline Hill for sacrifice. It was also a massive deadline for interest payments. Imagine if Tax Day and a religious festival happened at the exact same time. That was the Ides. People were focused on their wallets and their gods, not a conspiracy brewing in the shadows of the Senate.

The "beware" part? That allegedly came from a seer named Spurinna. According to the historian Suetonius, Spurinna warned Caesar that great danger would befall him no later than the Ides of March. On the actual day, Caesar supposedly saw the seer and joked, "The Ides of March have come," implying he was safe. Spurinna’s comeback was chilling: "Aye, Caesar; but not gone."

Why Did They Actually Kill Him?

It wasn't just "liberty." That’s the PR version.

To understand the motive, you have to understand Caesar’s ego. He had recently been named Dictator Perpetuo—dictator for life. This was a massive slap in the face to the Roman aristocracy. Rome was a Republic, built on the idea that no one man should have king-like power. By taking the title, Caesar basically told the Senate they were irrelevant.

He was also doing things that felt "un-Roman." He started wearing all-purple robes (the color of kings). He sat on a golden throne in the Senate. He even put his own face on coins, which was a level of narcissism the Romans usually reserved for the gods.

📖 Related: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

The conspirators, who called themselves the Liberatores (The Liberators), weren't all noble heroes. Some, like Brutus and Cassius, were genuinely worried about the death of the Republic. Others were just bitter. They had fought against Caesar in the civil war, been pardoned by him, and hated the fact that they owed their lives to his "mercy." Being forgiven by a tyrant is sometimes more insulting than being executed by one.

The Scene at the Theatre of Pompey

Here is a detail people often miss: Caesar wasn't killed in the Senate House. The actual Curia Julia was being rebuilt. The Senate met that day in a hall attached to the Theatre of Pompey.

It was a chaotic, messy, and unprofessional hit.

There were about 60 conspirators, but only a handful actually did the stabbing. They crowded around him under the guise of presenting a petition for the recall of an exiled brother. Tillius Cimber pulled down Caesar’s tunic from his shoulder—that was the signal. Casca struck the first blow, but he was nervous and only grazed Caesar’s neck.

Caesar fought back. He supposedly stabbed Casca with a stylus (a sharp writing tool). But then the rest of the mob descended. In the frenzy, the conspirators were so frantic they actually stabbed each other. Brutus was wounded in the hand by his own allies.

The "Et Tu, Brute?" Myth

We need to talk about those famous last words. Honestly, he probably said nothing.

The historian Suetonius reports that some witnesses claimed Caesar said, in Greek, "Kai su, teknon?" which translates to "You too, child?" or "You too, young man?" It was less of a poetic lament and more of a shocked realization or even a final curse. Brutus was much younger than Caesar, and there were long-standing rumors that Caesar had an affair with Brutus’s mother, Servilia. Some even whispered Brutus was his biological son, though the dates don't really support that.

Most likely? Caesar covered his head with his toga so no one would see him die and succumbed to 23 stab wounds. Only one of those wounds—the second one to the chest—was actually fatal, according to the physician Antistius, who performed history's first recorded autopsy.

The Massive Backfire

The Liberators thought they would be greeted as heroes. They expected the Roman people to cheer in the streets.

👉 See also: Boynton Beach Boat Parade: What You Actually Need to Know Before You Go

They were wrong.

The public loved Caesar. He had cleared their debts, given them grain, and expanded the empire. When Mark Antony delivered his famous funeral oration (which was real, though Shakespeare certainly spiced it up), he showed the crowd Caesar's blood-stained, tattered toga. The city erupted. The "Liberators" had to flee for their lives.

Instead of saving the Republic, the assassination killed it faster. It triggered a series of civil wars that ended with Caesar’s grand-nephew, Octavian (later Augustus), becoming the first official Emperor of Rome. The conspirators wanted to stop a king; they ended up creating an empire.

Modern Echoes: Why We Still Care

We see the Ides of March everywhere because the themes are universal. It’s a story about the "Great Man" theory of history, the fragility of democracy, and the law of unintended consequences.

In business, people use "the Ides of March" to describe a sudden boardroom coup or a hostile takeover. In politics, it’s the shorthand for a betrayal by one’s inner circle. It’s the ultimate reminder that the person sitting next to you at lunch might be the one holding the metaphorical dagger.

The fascination also persists because of the sheer drama. It is a perfect narrative arc. The warning, the arrogance, the betrayal, and the messy aftermath. Even the weather usually feels a bit "off" in mid-March, adding to the atmospheric weight of the date.

Historical Context You Should Know

To really "get" the Ides of March, you have to look at the surrounding culture. The Romans were incredibly superstitious. They believed in omens, bird-flight patterns, and the entrails of animals. To them, the assassination wasn't just a political event; it was a cosmic one.

- The Comet: Shortly after Caesar’s death, a massive comet appeared in the sky for seven days. People took this as proof that Caesar had become a god.

- The Dreams: Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, allegedly dreamed of him being murdered the night before and begged him not to go to the Senate.

- The Note: A man named Artemidorus supposedly tried to hand Caesar a scroll containing the names of the conspirators as he walked to the Theatre, but Caesar never read it.

Whether these are true or just "historical fan fiction" written years later by Plutarch and Suetonius is up for debate. But they show how the event transformed from a crime into a myth almost instantly.

The Cultural Footprint

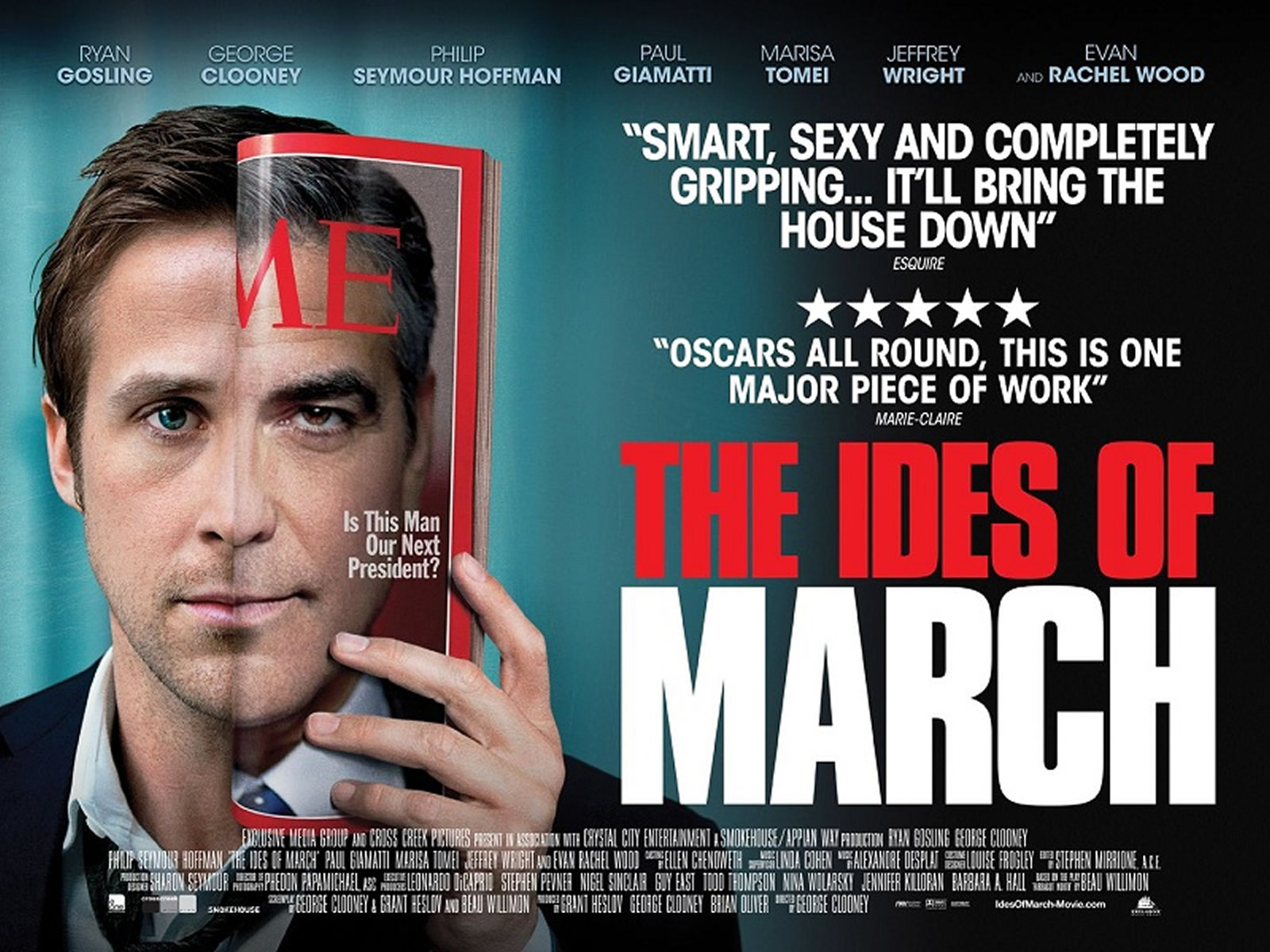

The Ides of March has become a brand. We have movies like the 2011 political thriller The Ides of March, and countless references in shows like Rome or Succession. It’s a trope.

✨ Don't miss: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

But it’s also a warning about polarization. The Roman Republic didn't collapse because of one man; it collapsed because the system could no longer handle its own internal conflicts. The Senate and the common people were at each other's throats long before the daggers were drawn. Caesar was just the catalyst.

When we look at the Ides of March today, we shouldn't just think about togas and ancient ruins. We should think about how quickly a stable society can descend into chaos when dialogue fails and power becomes the only currency that matters.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Own "Ides"

You don't have to be a Roman dictator to learn from this. History is just a set of patterns that keep repeating.

1. Watch for the "Echo Chambers"

The conspirators convinced themselves that everyone hated Caesar because they hated Caesar. They failed to read the room (or the city). Always check your assumptions against reality, especially if you're planning a major change in your career or organization.

2. Mercy has a Price

Caesar’s policy of clementia (mercy) was his downfall. He forgave his enemies and let them stay in power. In a modern context, this doesn't mean you should be ruthless, but it does mean you should be aware that "forgiving and forgetting" doesn't always change an adversary’s heart.

3. Timing is Everything

If Caesar had stayed home that day, the conspiracy might have fallen apart. Most of the senators were terrified and ready to bolt. The window for action was tiny. Whether you're launching a product or making a life move, the "Ides" teaches us that timing often matters more than the plan itself.

4. Respect the Institutions

The Republic died because people stopped believing in the rules. When individuals become more powerful than the systems meant to hold them, the Ides of March is usually the logical conclusion. Keep your ego in check and respect the structures that provide stability.

5. Read the Primary Sources

If you want the real story, don't just watch a movie. Read The Twelve Caesars by Suetonius or Parallel Lives by Plutarch. They are surprisingly gossipy, easy to read, and give you a much better "vibe" for what Rome was actually like than any textbook ever could.

The Ides of March isn't a curse, and it isn't just a date. It’s a mirror. It shows us what happens when ambition meets tradition and everything goes wrong. Stay sharp this March 15th—and maybe keep an eye on your calendar.