We’ve all seen that one image. You know the one—a hunched-over ape slowly straightening up, step by step, until it becomes a tall, spear-wielding man. It’s called the March of Progress. It’s iconic. It’s also total nonsense.

If you want to understand the human tree of evolution, you have to stop thinking about a ladder. Evolution doesn't climb. It wanders. It’s a messy, tangled thicket of branches where some paths lead to us and dozens of others just... stop. Dead ends. Evolutionary ghosts. For a long time, we thought we were the crown achievement of a straight line, but the reality is that for most of our history, we weren't alone. We shared the planet with other versions of "us."

The Tangle We Call Home

The old-school view was simple. Australopithecus turned into Homo habilis, who turned into Homo erectus, who eventually became us. Clean. Easy to memorize for a test. But then we started finding more bones.

In the last couple of decades, paleoanthropologists like Lee Berger and teams at the Max Planck Institute have blown that linear model apart. We found Homo naledi in a cramped cave in South Africa. We found the "Hobbits" (Homo floresiensis) on an island in Indonesia. These weren't necessarily our ancestors; they were our cousins. Some lived at the same time as Homo sapiens. Imagine a world where three or four different types of humans all existed at once, looking slightly different, using different tools, but all remarkably "human."

That’s the real human tree of evolution. It’s not a single trunk. It’s a bush.

💡 You might also like: iPhone Keeps Turning Off: Why Your Phone Is Quitting On You (And How To Fix It)

Why the "Missing Link" is a Myth

People love to talk about the missing link. It’s a catchy phrase. It suggests there’s just one puzzle piece lost in the dirt that will finally explain how a chimp-like ancestor became a person. But there is no single link. There are thousands of them.

Take Ardipithecus ramidus, or "Ardi." Found in Ethiopia and dating back about 4.4 million years, Ardi is a weird mix. She had a big toe for climbing trees but a pelvis that suggests she could walk on two legs, albeit awkwardly. She isn't the "link." She’s a snapshot of a transition that took millions of years. Evolution doesn't happen in a "eureka" moment where a baby is suddenly born with a larger brain. It’s a slow, agonizing grind of tiny changes.

The Bipedal Revolution

Walking on two legs changed everything. It’s arguably the most important pivot point in the human tree of evolution.

Why did we do it? Some say it was to see over tall grass on the savanna. Others think it was to stay cool—less surface area exposed to the sun. Or maybe it was just to carry more snacks. Whatever the reason, it happened early. Australopithecus afarensis, the species famous for the "Lucy" fossil, was walking upright over 3 million years ago.

But walking upright came with a massive cost. Our hips narrowed. This made childbirth incredibly dangerous and difficult compared to other primates. It also meant our babies had to be born "early" in terms of development because if their heads got any bigger in the womb, they wouldn't fit through the birth canal. This led to a long childhood where human infants are completely helpless, which forced us to develop tight-knit social structures.

Basically, walking on two legs forced us to start talking to each other.

The Brain Boom

Once our hands were free from walking, we started fiddling with things. Stones. Sticks. Fire.

About 2 million years ago, with the arrival of Homo erectus, brain size started to skyrocket. This is where the human tree of evolution gets really interesting. Homo erectus was the first of our kin to really look like us from the neck down. They were runners. They were travelers. They were the first to leave Africa and spread into Europe and Asia.

They also cooked.

Richard Wrangham, a Harvard primatologist, argues that cooking was the catalyst for the modern human brain. Raw food takes a lot of energy to digest. Cooked food is "pre-digested" by heat, meaning we could get more calories with less work. This extra energy fueled our most expensive organ: the brain.

The Cousins We Lost (And Kept)

We used to think Homo sapiens showed up and the Neanderthals just disappeared because we were smarter. That’s probably not true. Neanderthals had larger brains than we do. They buried their dead. They made jewelry. They cared for the sick.

We didn't just replace them; we absorbed them.

If you have European or Asian ancestry, about 1% to 4% of your DNA is Neanderthal. We found another group, the Denisovans, through a single finger bone in a Siberian cave. It turns out many people in Melanesia and East Asia carry Denisovan DNA too. The human tree of evolution isn't just about who survived—it's about who we invited over for dinner.

Homo sapiens weren't the "best" in a vacuum. We were likely just the most adaptable. Or maybe we were just the most aggressive. Or, as some genomic evidence suggests, maybe we were just better at living in larger groups, which allowed for better information sharing.

Modern Technology vs. Ancient Bones

The way we study this has changed. It’s not just about brushes and shovels anymore. It’s about paleogenetics.

We can now extract DNA from "dirt"—literally the sediment in caves where humans used to live—even if there are no bones left. This has completely shifted our understanding of the human tree of evolution. We are finding evidence of "ghost lineages"—groups of humans we know existed because their DNA shows up in ours, but we haven't even found their fossils yet.

It’s a bit like trying to build a family tree when half the relatives are invisible.

Common Misconceptions That Won't Die

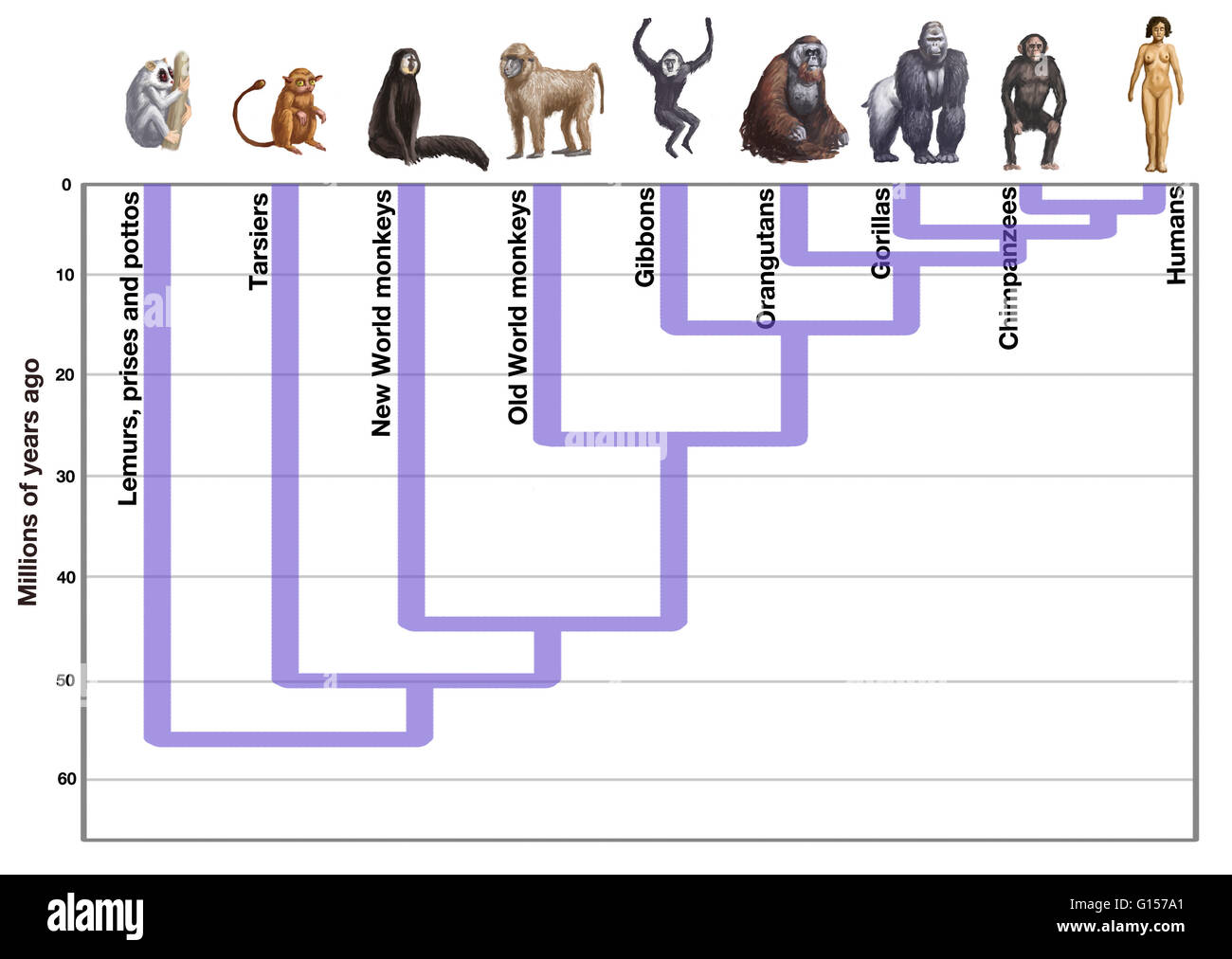

"If we evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?" This is the classic one. We didn't evolve from modern monkeys or chimps. We share a common ancestor. Think of it like cousins. You didn't "come from" your cousin; you both share a grandparent. About 6 or 7 million years ago, there was a primate that wasn't a chimp and wasn't a human. One branch of its descendants became them, and one branch became us.

The "Brain Size" Trap

A bigger brain doesn't always mean "smarter." Neanderthals had big brains, but they might have been wired differently, focusing more on vision and physical control than the complex social networking we do. It’s not just the size of the hardware; it’s the software that counts.Survival of the Fittest

People think this means "survival of the strongest." In evolution, "fitness" just means "how many kids did you have that survived?" Sometimes the "fittest" is the one who is the best at hiding, or the one who can eat a specific type of tuber that no one else likes.

Why It Matters Right Now

Understanding the human tree of evolution isn't just a history lesson. It’s a health lesson.

Many of the health issues we face today—obesity, back pain, autoimmune diseases—stem from the fact that our bodies are still tuned for the Pleistocene. We are "Stone Age" bodies living in a "Silicon Age" world. Our backs hurt because we are essentially modified quadrupeds. We get diabetes because our bodies are designed to store every scrap of sugar they can find, a trait that was a lifesaver 50,000 years ago but is a disaster in a world of unlimited soda.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Your Roots

If you want to move beyond the textbook and really understand where you came from, start with these steps:

- Get a DNA test with an emphasis on archaic ancestry. Companies like 23andMe or Ancestry can tell you exactly how much Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA you're carrying. It's a surreal feeling to know a piece of an extinct species is literally powering your cells.

- Visit the Smithsonian's Human Origins portal. They have one of the most up-to-date digital databases of fossils. Look at the skulls. Note how the brow ridges shrink and the foreheads grow over time.

- Read "Sapiens" by Yuval Noah Harari or "Kindred" by Rebecca Wragg Sykes. Harari gives the big-picture view of how we became a global force, while Sykes gives a deeply human, empathetic look at the Neanderthals.

- Explore the "Olduvai Gorge" virtual tours. This spot in Tanzania is often called the Cradle of Mankind. Seeing the landscape helps you realize why we had to change to survive.

- Look at your own body. Find your "palmaris longus" muscle (touch your pinky to your thumb and tilt your wrist up). If a tendon pops up, you have it. If not, you don't. It's a leftover muscle from when our ancestors used their forearms to swing through trees. It's a living piece of the human tree of evolution right on your arm.

We aren't the end of the line. Evolution hasn't stopped. We are just a mid-point in a story that started millions of years ago and will likely keep going long after we’re the ones being dug up by curious researchers.