Ever looked at a skeleton and wondered why the top half looks like a chaotic jigsaw puzzle compared to the solid, chunky pillars of the legs? Honestly, the human skeleton upper body is a structural paradox. It’s built for reach, not for weight. While your legs are essentially meat-wrapped telephone poles designed to keep you upright, your upper frame is a masterclass in compromise. You trade stability for the ability to reach the top shelf or throw a fastball. It's a high-wire act. If one tiny piece—like that thin, curved collarbone—snaps, the whole system basically stops working.

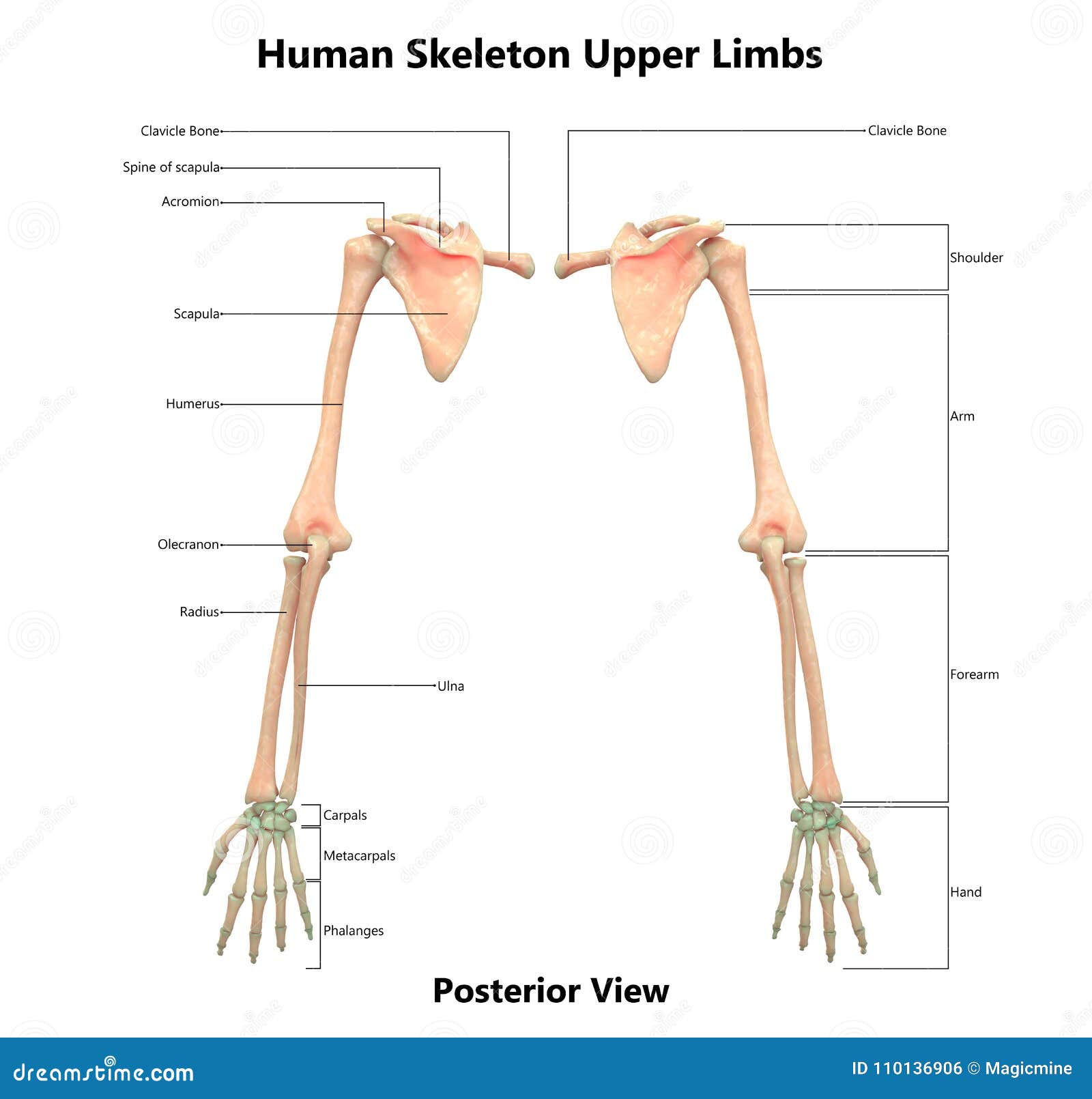

You’ve got 64 bones up there. Just in the arms and hands. Think about that.

📖 Related: Lose Weight Very Fast: What Most People Get Wrong About Rapid Fat Loss

The Scapula and the "Floating" Illusion

Most people think the shoulder is a simple ball-and-socket joint like the hip. It isn't. Not even close. The human skeleton upper body relies on the scapula (your shoulder blade) to do the heavy lifting, but the scapula isn't even "bolted" to your spine. It floats. It’s held in place by a complex web of about 17 different muscles. This is why you can shrug, rotate, and reach behind your back, but it's also why your rotator cuff is so prone to screaming in pain after a weekend of moving furniture.

The only bony connection between your entire arm and the rest of your skeleton is the clavicle. That’s it. One tiny, S-shaped bone acting as a strut. If you fall on an outstretched hand, the force travels up the arm and hits that strut. Because the clavicle is the "weak link" by design, it snaps to prevent the force from crushing your ribcage or damaging your spine. It's basically a biological circuit breaker.

The Rib Cage Is Not a Solid Box

We call it a "cage," but it’s more like a springy accordion. Your 12 pairs of ribs are masterpieces of flexibility. The first seven are "true ribs," meaning they attach directly to the sternum via costal cartilage. Then you have the "false ribs" and those weird "floating ribs" at the bottom that don't attach to the front at all.

Without this elasticity, you couldn't breathe. Every time you inhale, your rib cage expands. If it were a rigid box of solid bone, your lungs wouldn't have anywhere to go. Dr. Susan Standring, editor-in-chief of Gray's Anatomy, often highlights how the thoracic cage must balance the protection of the heart and lungs with the mechanical requirements of ventilation. It’s a tightrope walk.

Understanding the Humerus and the "Funny Bone" Myth

The humerus is the heavy hitter of the human skeleton upper body. It's the longest bone in your arm. But here’s the thing: the "funny bone" isn't a bone. When you hit your elbow and feel that electric zing, you’re actually compressing the ulnar nerve against the medial epicondyle of the humerus. It feels weird because the nerve is essentially unprotected there.

Evolutionary biologists often point out that our upper limb structure is a relic of our brachiating ancestors—the ones who swung through trees. We kept the mobility but changed the context. Now, instead of swinging through the canopy, we use that same range of motion to type on mechanical keyboards or scroll through TikTok. Our skeletons haven't quite caught up to our sedentary lifestyles.

The Forearm's Magic Trick

The radius and the ulna. Two bones. One job: rotation. When you turn your palm up (supination) or down (pronation), these two bones actually cross over each other.

- Stand with your palm up. The bones are parallel.

- Turn your palm down. The radius literally flips over the ulna.

This mechanical rotation is what allowed early humans to create tools, throw spears with accuracy, and eventually, perform surgery. Without this specific arrangement in the human skeleton upper body, your hands would be stuck in one position, making you about as dexterous as a Lego figurine.

Why Your Hands Have So Many Bones

Your wrist and hand are home to 27 individual bones. That is a ridiculous amount of hardware for such a small area. The carpal bones—eight tiny, pebble-like bones in the wrist—are arranged in two rows. They slide against each other to give you that fluid wrist flick.

📖 Related: Bed Rail for Elderly: What Most Families Get Wrong About Safety

- Scaphoid (the one everyone breaks)

- Lunate

- Triquetrum

- Pisiform

- Trapezium

- Trapezoid

- Capitate

- Hamate

If you've ever had carpal tunnel syndrome, you know the "tunnel" is a narrow passageway of bone and ligament. When the tendons in there get inflamed, they squeeze the median nerve. It’s a design flaw, honestly. We have too much stuffed into too small a space.

The Precision of the Phalanges

Your fingers don't actually have muscles in them. All the muscles that move your fingers are located in your forearm. They’re connected to your finger bones (phalanges) by long tendons, sort of like a marionette puppet. This is why you can have such thin, delicate fingers capable of playing a violin; if the muscles were in the fingers themselves, your hands would be too bulky to do anything useful.

The Sternum: The Anchor

In the center of your chest sits the sternum. It looks a bit like a necktie. It’s made of three parts: the manubrium at the top, the body in the middle, and the xiphoid process at the bottom.

✨ Don't miss: Is Drinking Apple Juice Good for You? What the Nutrition Science Actually Says

The xiphoid process starts as cartilage and slowly turns to bone as you age. It’s the reason why CPR instructors tell you to be careful where you place your hands; if you press too low, you can snap that little piece of bone right off. It’s a grim reminder of how fragile the human skeleton upper body can be under pressure.

Maintaining Your Structural Integrity

Since the upper body skeleton is largely suspended by muscle, your posture is everything. "Tech neck" or "hunched shoulders" isn't just an aesthetic issue; it’s a mechanical one. When your head slumps forward, the weight distribution on your cervical spine shifts dramatically. Your head weighs about 10-12 pounds. For every inch it moves forward, the effective weight on your neck doubles.

Actionable Maintenance for Your Frame

To keep the human skeleton upper body functioning without constant "creaks" and "pops," you have to treat it like the high-performance machine it is.

- Focus on Scapular Stability: Don't just work your "mirror muscles" (chest and biceps). If you don't strengthen the muscles that hold your shoulder blades in place, like the rhomboids and lower traps, your shoulders will eventually roll forward and cause impingement.

- Load Bearing is Key: Bone is living tissue. It follows Wolff's Law, which basically says bone grows or remodels in response to the forces placed upon it. If you don't do some form of resistance training, your bones—especially the delicate ones in the wrist and humerus—will lose density over time.

- Vitamin D and Calcium: It sounds like a cliché, but it’s real. Without Vitamin D, your body can’t absorb the calcium it needs to keep that "circuit breaker" clavicle strong.

- Mind the Ergonomics: If you spend eight hours a day at a desk, your radius and ulna are likely perpetually crossed, and your scapulae are stretched thin. Take breaks to "reset" your skeleton to its neutral, anatomical position.

The upper frame is a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering that sacrificed brute strength for unparalleled versatility. It allows us to paint, build, hug, and defend ourselves. It's a complex, fragile, and utterly fascinating system that requires more than just "not breaking it" to stay healthy. It requires movement.

Stop sitting still. Go hang from a pull-up bar for thirty seconds. Let your scapulae decompress. Your skeleton will thank you for remembering it isn't just a coat hanger for your skin.