You probably think you know the story. It’s that repetitive, slightly annoying rhythmic loop about a guy named Jack and the chaotic chain of events triggered by some stored malt. But honestly, The House That Jack Built is a lot weirder than your average bedtime story. It’s not just a poem for toddlers; it’s a linguistic fossil that has survived for centuries, influencing everything from 19th-century political cartoons to Lars von Trier’s disturbing cinema.

The origins are murky. Most scholars point toward the mid-1700s, specifically Nurse Lovechild's Legacy, published in 1746. However, that’s just the first time it hit the printing press. Like most folk traditions, it was likely kicking around oral circles long before that. It’s a "cumulative tale," a structural cousin to "The Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly" or the Passover song "Chad Gadya." It builds. It layers. It creates a linguistic tower that eventually collapses under its own weight.

Where Did The House That Jack Built Actually Come From?

History isn’t a straight line. If you look at the 16th-century Hebrew chant Chad Gadya (One Little Goat), the structural DNA is identical. You have a father who buys a goat, then a cat eats the goat, a dog bites the cat, a stick beats the dog, and so on. It’s a cosmic chain of causality. By the time it morphed into the English version we know, the religious allegory was stripped away, replaced by a strangely suburban English nightmare involving rats, cows with crumpled horns, and "all-forlorn" milkmaids.

James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, the legendary 19th-century collector of nursery rhymes, documented various versions of the text. He noted that while the characters seem random, they represent a snapshot of agrarian life. It’s a world where a single point of failure—the malt getting damp or eaten—cascades into a social catastrophe involving the church and the legal system.

It’s about consequences. Small things matter.

The Characters You Forgot

We all remember the rat and the cat. But the later verses get increasingly specific and, frankly, a bit depressing. You have the "man all tattered and torn" who kisses the "maiden all forlorn." Then comes the "priest all shaven and shorn" to marry them. It’s a weirdly complete ecosystem of 18th-century poverty and providence.

Early illustrators like Randolph Caldecott turned these verses into visual masterpieces. Caldecott’s 1878 version is widely considered the gold standard. He didn't just draw a house; he drew a narrative world where the characters had distinct, often weary, personalities. His work was so influential that the Caldecott Medal for children’s books is named after him. He saw the humor in the chaos. He saw that Jack's house wasn't just a building—it was a metaphor for a society where everyone is bumping into each other's problems.

🔗 Read more: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The Psychological Hook: Why Our Brains Love Cumulative Stories

There is a reason this rhyme sticks. Cognitive scientists often look at cumulative tales as a form of "chunking." You aren't memorizing ten different sentences. You are memorizing one growing sentence.

It’s addictive.

This structure creates a sense of inevitable momentum. Once the "dog that worried the cat" enters the fray, the listener's brain anticipates the "cow with the crumpled horn." It’s a rhythmic safety net. However, in modern literature and film, this "safety" is often subverted. When a creator references The House That Jack Built, they are usually hinting at a cycle that cannot be stopped—a snowball rolling down a hill of its own making.

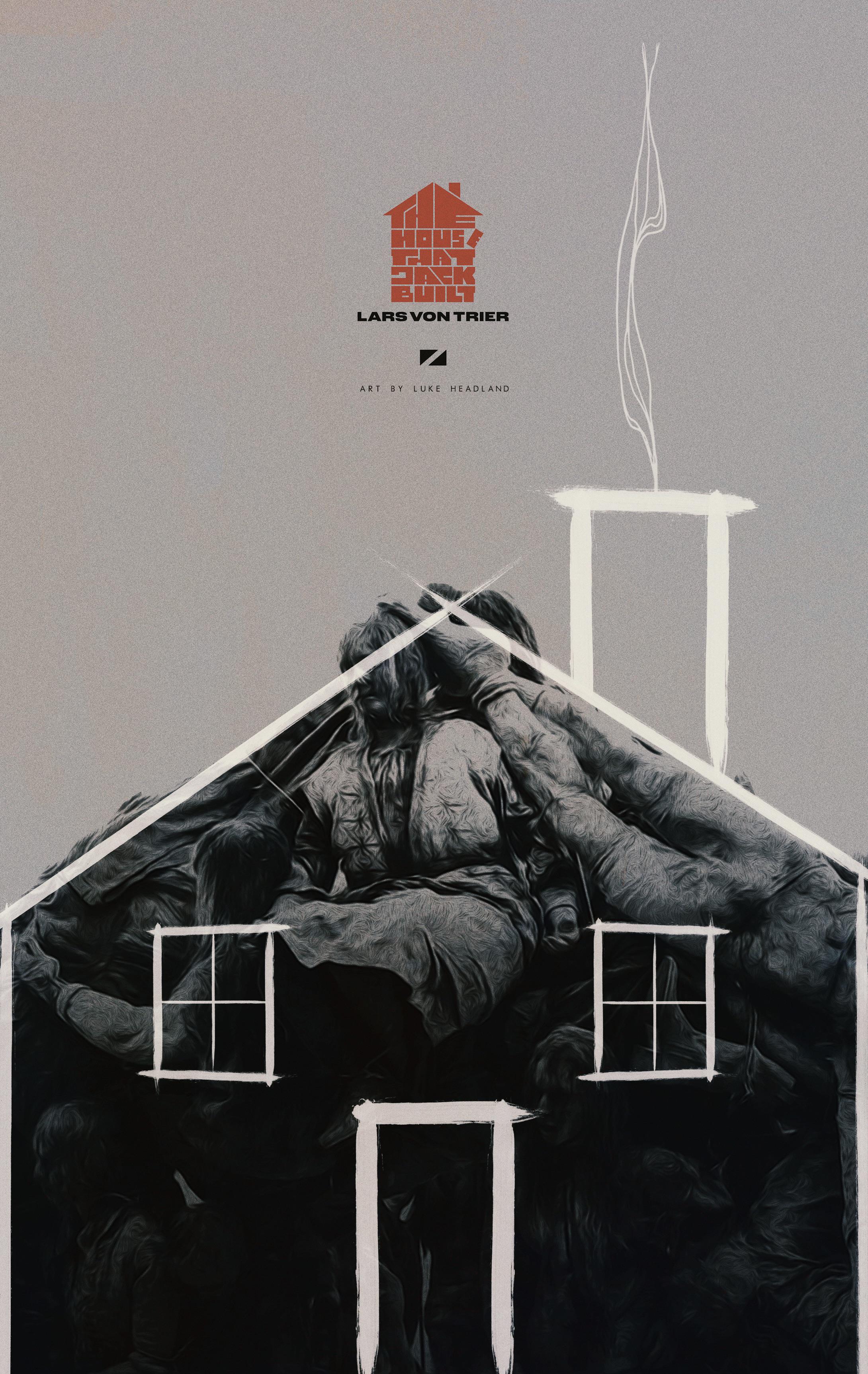

Consider the 2018 film by Lars von Trier of the same name. It’s a brutal, controversial look at a serial killer who views his crimes as architectural "incidents." Von Trier uses the nursery rhyme structure to show how Jack (the killer) builds his own legacy out of horror. It’s the ultimate dark parody. The "malt" in his house isn't grain; it's human remains. It’s a far cry from Caldecott’s whimsical drawings, yet the core logic is the same: one action necessitates the next.

More Than Just Malt: The Political Satire Phase

In the 1800s, this rhyme was a weapon. Satirists used the "This is the..." format to mock everything from the British government to the Peterloo Massacre.

William Hone and illustrator George Cruikshank published The Political House that Jack Built in 1819. It was a scathing critique of the Regency government. Instead of a rat, they had the "Wealth that lay in the House that Jack built," representing the public's tax money. The "Man all tattered and torn" became the starving English people. It was a viral sensation, selling over 100,000 copies—a massive number for the time.

💡 You might also like: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

It worked because everyone knew the rhythm. You could swap the lyrics, but the beat remained. It made complex political corruption easy to digest. If you could explain the downfall of the British economy using the logic of a cat and a rat, you could radicalize the working class.

Modern Echoes and Pop Culture

The influence hasn't stopped. Think about the song "Everything is Everything" or the way modern hip-hop uses "internal rhyming" and cumulative buildup. Even in video games or complex TV narratives like Breaking Bad, we see the "Jack" effect. Walter White builds a house—a drug empire—where every "rat" (informant) leads to a "cat" (enforcer), eventually leading to a "priest" (the moral reckoning).

It is a blueprint for tragedy.

Interestingly, many people confuse the rhyme with the concept of a "house of cards." They aren't the same. A house of cards is fragile because of its construction. The House That Jack Built is fragile because of its inhabitants. It’s a drama of proximity.

Fact-Checking the Common Myths

Many people think Jack is a specific historical figure. He isn't. "Jack" was simply the "Everyman" name of the 17th and 18th centuries—think Jack the Giant Killer or Jack and Jill. He’s a placeholder for anyone who tries to build something in an unpredictable world.

Another myth is that the rhyme is a secret code for the Great Fire of London. There is zero evidence for this. While the "house" might burn in some later, darker folk variations, the original text is much more concerned with the mundane frustrations of agriculture and marriage than with urban conflagration.

📖 Related: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

How to Use the "Jack" Principle in Your Own Work

Whether you’re a writer, a business owner, or just someone trying to understand why things go wrong, the structure of this rhyme offers some surprisingly practical insights.

- Identify your "Malt": What is the core asset or idea at the center of your project? If the malt isn't protected, the rest of the house doesn't matter.

- Map the Dependencies: In the rhyme, the dog depends on the cat, which depends on the rat. In real life, your supply chain or your daily habits work the same way. If you change one link, you change the whole building.

- Embrace the Build: When telling a story or pitching an idea, use the cumulative method. Start small. Add one layer. Then add another. It’s the most natural way for the human brain to process information.

Moving Forward With Jack

The next time you hear or read The House That Jack Built, don’t just dismiss it as a kids' poem. Look at the layers. Think about the "tattered and torn" characters who are just trying to get by in a world that keeps adding more chaos to their doorstep.

If you want to dive deeper into the history of these types of stories, your best bet is to look up the works of Iona and Peter Opie. They spent decades researching the "lore and language of schoolchildren" and provide the most rigorous academic look at how these rhymes evolve over centuries. You can also check out the digital archives of the British Library, which holds several original 19th-century chapbooks featuring Jack and his ill-fated malt.

Stop looking at it as a static poem. It’s a living document of how we perceive cause and effect. Build your own "house" wisely, and for heaven's sake, keep an eye on the rat.

To actually apply this knowledge, start by auditing your own "house"—the projects or systems you’ve built recently. Look for the "rat" or the single point of failure that could trigger a cascade of issues. Understanding the chain of causality isn't just a literary exercise; it's a diagnostic tool for life. Try writing your own cumulative verse about a current problem you're facing. It sounds silly, but it's an incredibly effective way to see how one small stressor is actually connected to much larger, more complex frustrations in your world.