Forget the white and red roses for a second. That’s mostly Tudor PR work. If you want to understand the House of York and House of Lancaster, you have to look at a messy family tree and a king who probably shouldn't have been on the throne in the first place. It wasn't just a "war." It was a decades-long property dispute with knights and heavy axes.

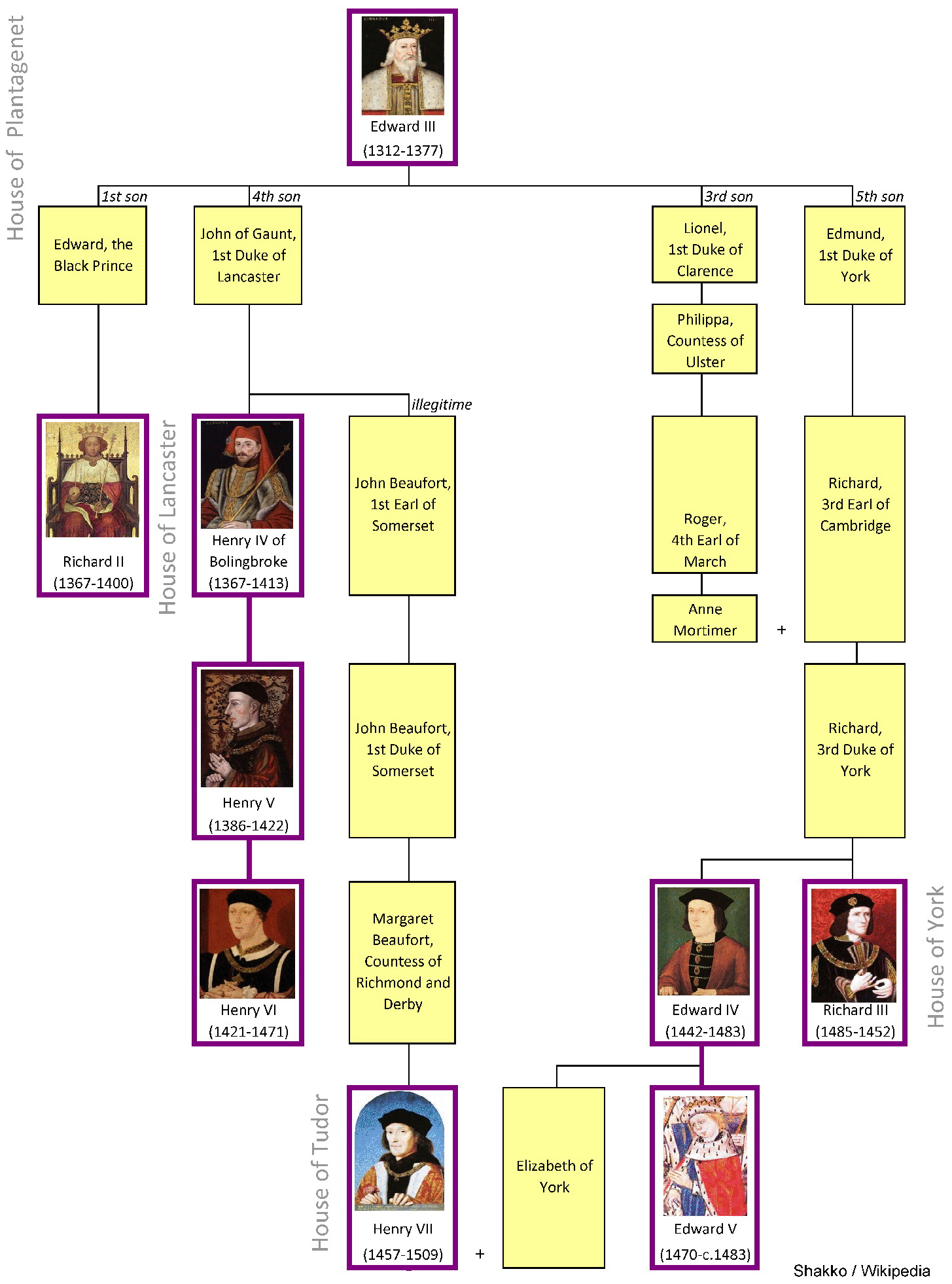

Basically, both of these houses were branches of the same family tree: the Plantagenets. They all traced their bloodline back to Edward III. The whole mess started because Edward had too many sons, and those sons had very ambitious children.

The Original Sin of the House of Lancaster

Henry IV is usually the one people point to when they ask where it all went wrong. He was a Lancaster. In 1399, he jumped the queue. He overthrew his cousin, Richard II, who was—by all accounts—a pretty terrible king, but he was the rightful king. When Henry IV took the crown, he broke the rules of succession. This created a "might makes right" vibe that hung over England for a century.

Henry V managed to make everyone forget about this because he was a rockstar at the Battle of Agincourt. People tend to ignore a questionable legal claim when you're busy conquering France. But then he died young. He left the throne to a nine-month-old baby, Henry VI. That’s when the House of York and House of Lancaster rivalry really turned toxic.

Henry VI was nothing like his dad. He was deeply pious, hated violence, and suffered from bouts of mental illness where he wouldn't speak for over a year. While he was catatonic, the country started to rot. Local lords were fighting their own private wars. The treasury was empty. England was losing all the land in France that Henry V had won.

Enter Richard, Duke of York

Richard of York was the richest man in England. He also had a better bloodline claim to the throne than the King did, if you followed the female line of descent. Initially, Richard didn't even want to be king. He just wanted to be the guy in charge of the King’s council because he thought the King's current advisors—specifically the Duke of Somerset—were running the country into a ditch.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

It’s kind of wild how personal it was. This wasn't a grassroots revolution. It was a handful of cousins getting mad at each other in drafty castles. The "Wars of the Roses" name? That came much later. Sir Walter Scott actually helped popularize the term in the 19th century. During the 1450s, people just called it a nightmare.

Why the House of York Actually Won (At First)

The House of York had a secret weapon: Edward IV. After Richard of York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield—and his head was stuck on a gate with a paper crown for a laugh—his son Edward took over.

Edward was six-foot-four, handsome, and an absolute unit on the battlefield. He never lost a battle he commanded personally. He was the first Yorkist king, and he basically turned the House of York and House of Lancaster feud into a total rout. He was a master of branding. He knew that the people in London were tired of the weak, sickly Henry VI. They wanted a guy who looked like a king and acted like one.

Edward IV’s reign was actually pretty stable for a while, but the House of York had a habit of self-destructing. Edward married Elizabeth Woodville, a "commoner" widow with a massive, power-hungry family. This ticked off his best friend, the Earl of Warwick (known as the Kingmaker), who eventually flipped sides and went over to the Lancastrians.

The drama is endless. You have brothers betraying brothers. George, Duke of Clarence, actually rebelled against his brother Edward IV twice before finally being executed—legend says he was drowned in a vat of Malmsey wine. Whether that’s true or just a cool story, it shows how vicious the Yorkist internal politics were.

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

The Lancaster Comeback and the Tudor Twist

By the time we get to the 1480s, the House of York and House of Lancaster conflict seemed to be over. The Yorkists had won. But then Edward IV died unexpectedly. His brother, Richard III, took the throne after declaring Edward’s kids illegitimate. The "Princes in the Tower" disappeared.

This was the opening the Lancastrians needed, but there was a problem: they were almost all dead.

The only guy left with even a drop of Lancaster blood was Henry Tudor. Honestly, his claim was shaky at best. He was descended from an illegitimate line (the Beauforts) on his mother's side. He had been living in exile in France for years. He wasn't even a "Lancaster" by name.

But he was the only alternative to Richard III.

When Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485, he did something brilliant. He didn't just claim the throne for the House of Lancaster. He married Elizabeth of York—the daughter of Edward IV. He literally fused the two houses together. He created the Tudor Rose, which combined the white petal and the red petal.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

It was the ultimate PR move. It told the people: "The fighting is over. We are one family now."

Realities of the Conflict

- Casualties: It wasn't just knights. Thousands of common soldiers died at Towton, which remains likely the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil. Estimates suggest 28,000 men died in a single day during a snowstorm.

- The "Roses" Myth: Most soldiers didn't wear rose badges. They wore the "livery" of their specific lord. If you fought for Warwick, you wore a ragged staff. If you fought for York, you might wear a sun in splendour.

- Social Impact: Remarkably, while the nobles were butchering each other, the legal system and the economy for the average peasant didn't collapse entirely. Life went on, just with a lot more anxiety about who was wearing the crown this week.

How to Trace the History Yourself

If you’re actually interested in the House of York and House of Lancaster, don't just read Shakespeare. He was writing for a Tudor queen, so he made the Yorkists look like villains and the Lancastrians look like tragic heroes.

Go to the sources. Look at the Paston Letters. These are real letters written by a family during the wars. They talk about the fear of soldiers coming through their village and the confusion of not knowing who was actually in charge of the country.

Visit the sites. Middleham Castle in North Yorkshire was Richard III’s childhood home. You can still feel the weight of the history there. Or go to St Albans, where the first blood was actually spilled in 1455. It’s a quiet town now, but it was the epicenter of a dynastic earthquake.

Understanding this conflict isn't just about memorizing dates. It’s about seeing how fragile power is. One weak king or one ambitious cousin is all it takes to flip a country upside down. The House of York gave us the concept of a "modern" Yorkist administration, while the House of Lancaster gave us the foundation of the Tudor golden age. They are two sides of the same coin, and England wouldn't be England without their fight.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Read the Paston Letters: Get the "Broadview Anthology" version. It’s the closest thing you’ll get to a 15th-century Twitter feed. It grounds the grand political narrative in real, terrifying human experience.

- Verify the Sites: If you visit Towton, go with a guide or a detailed map. The battlefield is huge and mostly looks like empty fields, but knowing where the "Bloody Meadow" is changes your perspective on the scale of the violence.

- Check the Genealogy: Look up the "Legitimization of the Beauforts." It explains why Henry Tudor’s claim was so controversial and why he had to rely on "Right of Conquest" rather than just his bloodline.

- Avoid the "Rose" Bias: When watching documentaries or reading books, check if the author acknowledges that the "Wars of the Roses" is a retrospective name. If they treat the roses as primary military symbols, they're probably glossing over the nuances.