Red is the color of life. At least, that’s what our own bodies tell us every time we scrape a knee or get a paper cut. But nature doesn't always play by the rules of human biology. If you’ve ever wondered which animal has blue blood, you’re actually looking for a group of creatures that swapped iron for copper millions of years ago. It’s not just one weird alien-looking fish in the deep sea. It’s a whole collection of invertebrates, ranging from the common garden snail to the prehistoric horseshoe crab.

Blue blood isn't a stylistic choice. It's high-stakes chemistry.

While our blood relies on hemoglobin—a protein built around iron—these "blue-blooded" animals use hemocyanin. When oxygen hitches a ride on iron, it turns rust-red. When it binds to copper? It turns a striking, bright cerulean.

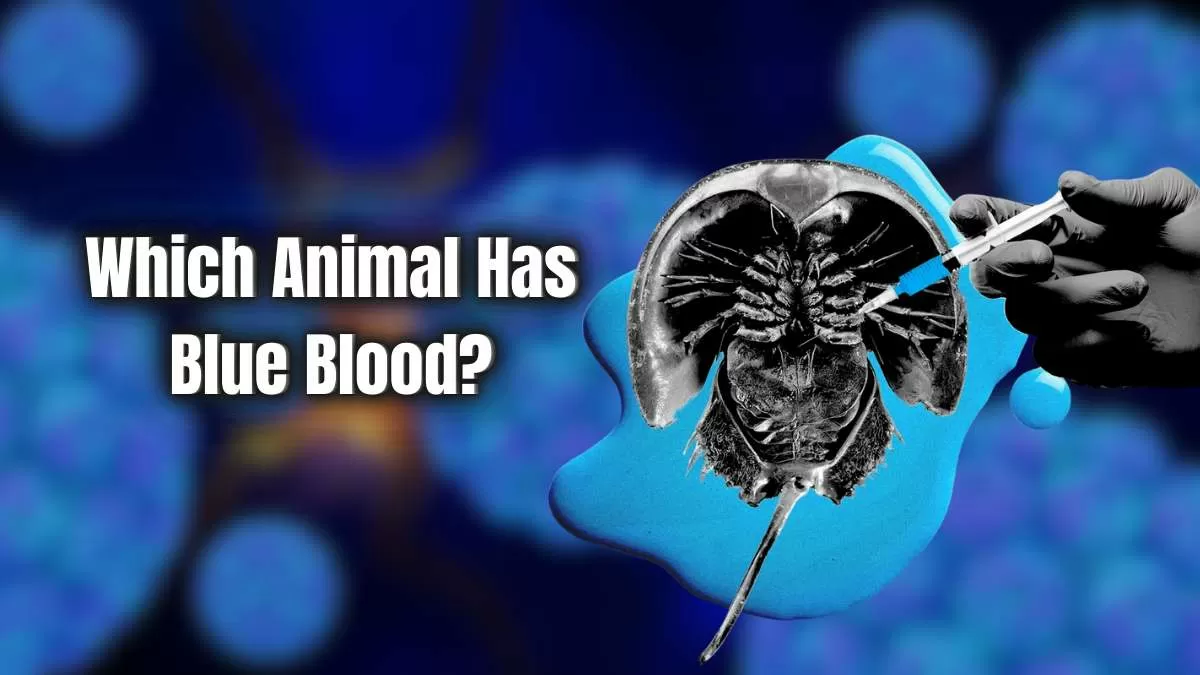

The Horseshoe Crab: A Medical Miracle in Blue

Honestly, the horseshoe crab is the celebrity of this world. It’s often the first thing people think of when they ask which animal has blue blood, and for good reason. These "living fossils" have been scuttling around the ocean floor for 450 million years. That's longer than dinosaurs. That’s longer than trees.

They aren't actually crabs, though. They’re more closely related to spiders and scorpions.

Their blood is iconic. If you saw it in a jar, you’d think it was a prop from a sci-fi movie. But this liquid isn't just pretty; it’s vital to your health. Horseshoe crab blood contains a very specific clotting agent called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL). This stuff is hyper-sensitive to endotoxins, which are nasty byproducts of bacteria.

If there is even a microscopic trace of bacterial contamination in a batch of vaccines or a new IV drip, the horseshoe crab blood will clot instantly into a gel.

Because of this, the pharmaceutical industry has relied on them for decades. Every single surgical implant and vaccine you’ve ever had was likely tested using the blue blood of these ancient creatures. Every year, hundreds of thousands of horseshoe crabs are harvested, "bled" in a lab, and then released back into the wild. It sounds like something out of a horror novel, but it’s the backbone of modern biomedical safety.

There’s a catch. We’re starting to realize the process isn't as harmless as we once thought. Conservationists like those at the Coastal Resources, Inc. have pointed out that many crabs don’t survive the return to the ocean, or they struggle to breed afterward. This has led to a massive push for synthetic alternatives like Recombinant Factor C (rFC), though the medical industry has been slow to fully pivot.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Why Copper? The Science of the Blue Hue

You might be thinking, "If red blood works so well for us, why did these guys go the copper route?"

Evolution doesn't strive for perfection; it settles for what works in a specific neighborhood. Hemocyanin—the copper-based protein—is actually much better at transporting oxygen in cold environments with low oxygen pressure. This is why you see blue blood in the deep ocean or in creatures that live in freezing temperatures.

Take the Antarctic octopus (Pareledone charcoti).

In the frigid, sub-zero waters of the Southern Ocean, iron-based hemoglobin becomes thick and inefficient. It’s like trying to pump molasses through a straw. Copper-based blood stays fluid and functional. It allows the octopus to survive in conditions that would literally freeze the circulatory system of a mammal.

It’s not just octopuses, either. Most cephalopods—squids, cuttlefish, and the like—are rocking the blue stuff. These animals have three hearts just to keep that thick, copper-rich blue blood moving. They are high-performance machines, but they burn through energy fast.

The Common Suspects: Snails, Spiders, and Slugs

You don't have to go to the bottom of the ocean to find which animal has blue blood. You might just need to go to your backyard.

Most mollusks and many arthropods use hemocyanin. This includes:

- Common garden snails.

- Slugs (yes, even the ones eating your hostas).

- Spiders of almost every variety.

- Scorpions.

- Lobsters and shrimp.

It’s a bit weird to think about, right? A tarantula has more in common, blood-wise, with a deep-sea giant squid than it does with you.

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

When a spider gets injured, you don't see a puddle of blue. That's because their blood (technically called hemolymph) is often quite clear when it isn't oxygenated. Once it's exposed to the air, the copper reacts and the blue tint becomes more apparent, though in small insects, it’s often too faint for the naked eye to catch without a microscope.

The Weird Outliers: Green, Clear, and Yellow Blood

Nature loves to make things complicated. While we’re focusing on blue, some animals decided to go in completely different directions.

There are certain species of lizards in New Guinea, like the green-blooded skink (Prasinohaema virens). Their blood is a vivid, lime green. This isn't because of copper or iron, but because of a massive buildup of biliverdin. In humans, biliverdin is toxic and causes jaundice. For these skinks, it’s a localized superpower that might actually protect them against parasites like malaria.

Then you have the Ocellated icefish. These ghosts of the ocean live in the Antarctic and have blood that is completely clear. They have no hemoglobin and no hemocyanin. They don't have red blood cells at all. Because the water is so cold and so oxygen-rich, the oxygen just dissolves directly into the plasma of their blood.

It’s efficient, but it makes them incredibly fragile. If the water temperature rises even a few degrees, they simply can't get enough oxygen to survive.

The Conservation Crisis of the Blue-Bloods

We owe a lot to the animals that carry blue blood, specifically the horseshoe crab.

In the United States, the Atlantic horseshoe crab population is under immense pressure. It’s not just the biomedical bleeding. They are also used as bait for whelk and eel fishing. Their eggs are the primary food source for migrating shorebirds like the Red Knot. When the crab population dips, the birds starve. Everything is connected.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists the American horseshoe crab as "Vulnerable."

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

We are at a crossroads where technology can finally replace the need for animal blood in labs. Eli Lilly, a major pharmaceutical company, has been a leader in adopting synthetic testing methods. However, the transition is bogged down by regulatory hurdles and a "if it ain't broke, don't fix it" mentality in global health departments.

How to Help and What to Do Next

If you’re fascinated by the world of blue-blooded creatures, you can actually contribute to their survival.

First, look into "citizen science" programs. If you live on the East Coast of the U.S., organizations like Project Limulus allow volunteers to help tag horseshoe crabs during their spawning season in May and June. This data is vital for tracking population health.

Second, be a conscious consumer. If you’re interested in marine life, support sustainable seafood practices that minimize "bycatch," which often kills deep-sea mollusks and crustaceans.

Finally, stay informed about the shift to synthetic LAL. The more public interest there is in protecting these prehistoric "blue bloods," the faster the medical industry will move toward lab-grown alternatives.

Quick Facts Checklist

- Which animal has blue blood? Horseshoe crabs, octopuses, squids, spiders, and most snails.

- The secret ingredient: Copper (Hemocyanin) instead of Iron (Hemoglobin).

- Human impact: We use horseshoe crab blood to test the safety of almost all injectable drugs.

- The color shift: It’s often clear inside the body and turns blue when exposed to oxygen.

Nature is rarely just one color. While we might feel like the protagonists of the planet, we’re actually in the minority when it comes to blood chemistry. The blue-blooded creatures have been here much longer than we have, and if we’re careful, they’ll be here long after we’re gone.

Actionable Insight: If you find a horseshoe crab flipped on its back at the beach, don't pick it up by the tail—that can injure its spine. Gently flip it over by the sides of its shell and let it crawl back to the water. You might just be saving a creature that could one day save your life.