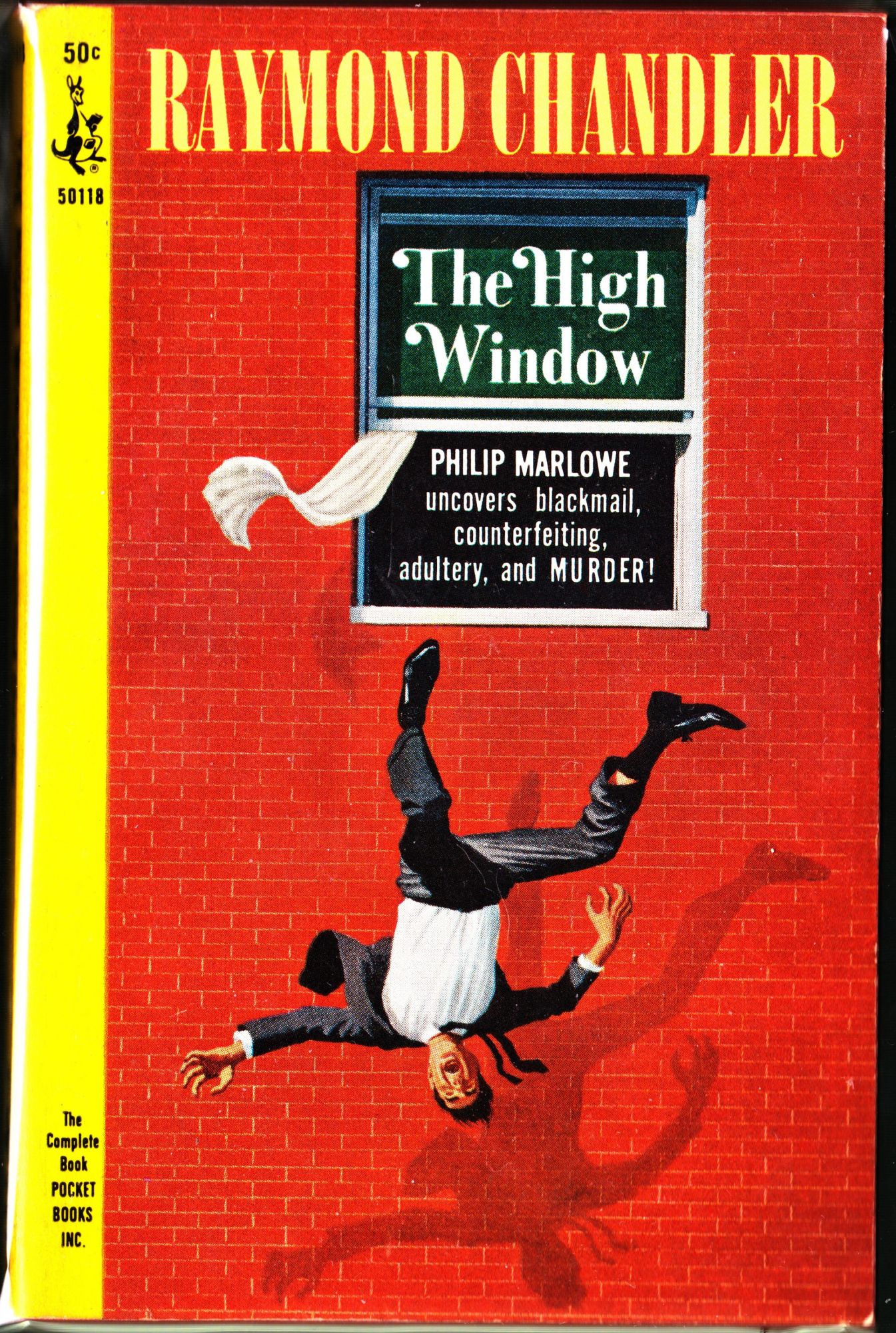

You’ve probably heard the knock on Raymond Chandler. People say his plots are a mess. They say he didn't even know who killed the chauffeur in The Big Sleep. Well, fine. If you want a clockwork puzzle, go read Agatha Christie and enjoy your vicarage tea. But if you want to feel the smog of 1940s Pasadena in your lungs, you read The High Window.

Published in 1942, this was Chandler’s third outing with Philip Marlowe. It is often the "forgotten" middle child. It sits between the breakout success of Farewell, My Lovely and the polished brilliance of The Lady in the Lake. Honestly? That is a mistake. This book is the leanest, meanest, and most psychologically damaged thing Chandler ever wrote.

The Case of the Brasher Doubloon

It starts with a coin. Not a body. Not a missing girl. Just a rare gold coin called the Brasher Doubloon. Marlowe gets summoned to a tomb-like mansion in Pasadena by Elizabeth Bright Murdock. She is a powerhouse. A "dried-up husk" of a woman who spends her days drinking port and bullying her mousy secretary, Merle Davis.

🔗 Read more: Why Movies With Female Leads Action Still Struggle At The Box Office

Mrs. Murdock claims her son’s estranged wife, a nightclub singer named Linda Conquest, stole the coin. Simple, right? Marlowe thinks so. He’s wrong.

The story spirals fast. We get a counterfeit coin scheme. We get a low-rent detective named George Anson Phillips who ends up dead in a rooming house. We get a coin dealer, Elisha Morningstar, who takes a bullet. Basically, everyone who touches this gold coin ends up as a cooling corpse.

But the coin is a MacGuffin. It’s a shiny distraction. The real story is about the Murdock family’s "high window." Years ago, Mrs. Murdock’s first husband, Horace Bright, fell out of a window. Or was he pushed? The trauma of that fall hangs over the house like a shroud.

Why The High Window Hits Different

Most noir is about the streets. This one is about the house. Chandler takes the "Manor House" mystery and guts it. Instead of a cozy library, he gives us a stifling atmosphere of domestic tyranny.

The Psychology of Merle Davis

Merle is the heart of the book. She’s terrified of everything. She has a "nervous condition." Everyone treats her like a broken doll. Mrs. Murdock has spent years convincing Merle that she—Merle—was the one who pushed Horace Bright. It’s a classic gaslighting move.

Marlowe isn't just a detective here. He’s a social worker with a gun. He realizes that solving the murders doesn't matter if he can't save this girl’s soul. The moment he takes her away from that house is one of the few genuinely "heroic" moments in the entire Marlowe canon. He doesn't get the girl; he rescues a human being.

The Writing Style

Chandler was feeling himself on this one. The similes are legendary.

- "He had a face like a lost battle."

- "From 30 feet away she looked like a lot of class. From 10 feet away she looked like something made up to be seen from 30 feet away."

The dialogue is fast. Brutal. It’s like watching a tennis match played with hand grenades. Marlowe’s interactions with the police—specifically Detective-Lieutenant Jesse Breeze—show a man who is tired of the system. He knows the law and justice are rarely on speaking terms.

What Most People Get Wrong

The biggest misconception about The High Window is that it’s a "minor" work. Critics at the time, and even Chandler himself in his darker moods, felt it lacked the "action" of his earlier books.

He once wrote to his publisher: "No action, no likeable characters, no nothing. The detective does nothing."

He was being too hard on himself. Marlowe does plenty. He navigates a web of blackmail involving a guy named Vannier. He pieces together a counterfeiting ring. He discovers that the "villain" isn't a gangster from the underworld, but the "respectable" lady in the Pasadena mansion.

This is the book where Chandler proves that the real "mean streets" aren't just in the alleys of Bunker Hill. They’re in the hallways of the rich. The corruption isn't just bribery; it's the way powerful people consume the lives of the weak.

The 1940s Los Angeles Setting

You can't talk about Chandler without talking about the city. In 1942, LA was changing. The funicular railway (Angels Flight) gets a shout-out. The "yellow clay banks" of Hill Street. It’s a city of neon signs and "quiet voices whispering of love or 10%."

Chandler captures the transition of California from a frontier to a corporate wasteland. The Murdocks represent the old money trying to keep their secrets buried under the new pavement.

Actionable Insights for Readers and Writers

If you’re coming to this book for the first time, or re-reading it, look past the "whodunit."

- Watch the power dynamics. Notice how Mrs. Murdock uses her money to silence the truth. It's a study in institutionalized bullying.

- Observe Marlowe’s code. He refuses to turn in his client's son, Leslie, despite Leslie being a murderer. Why? Because the law is a blunt instrument that would crush Merle in the process. Marlowe’s justice is personal.

- Study the descriptions. If you’re a writer, Chandler is your textbook. He doesn't describe a room; he describes how a room makes you feel.

The ending of the novel is unusually quiet. No big shootout. No dramatic arrest. Marlowe just drives Merle back to her parents in Wichita. He leaves the Murdocks to rot in their own history. It’s a clean break from a dirty situation.

🔗 Read more: The Chaos and Genius of the Saturday Night Live Original Cast Members 1975

If you want to understand the evolution of the hard-boiled hero, you have to look through The High Window. It’s the moment Philip Marlowe stopped being just a "tough guy" and started being a "man of honor" in a world that had none left to give.

Next Steps for the Chandler Fan:

- Read the source material: If you've only seen the movies (The Brasher Doubloon or Time to Kill), go back to the text. The 1947 film The Brasher Doubloon loses the psychological edge of the book.

- Compare it to "The Simple Art of Murder": Read Chandler’s famous essay on the genre alongside this novel. You’ll see him practicing exactly what he preached about the "man who is not himself mean."

- Explore the 1942 context: Consider how the early years of WWII influenced the grim, claustrophobic tone of the story.