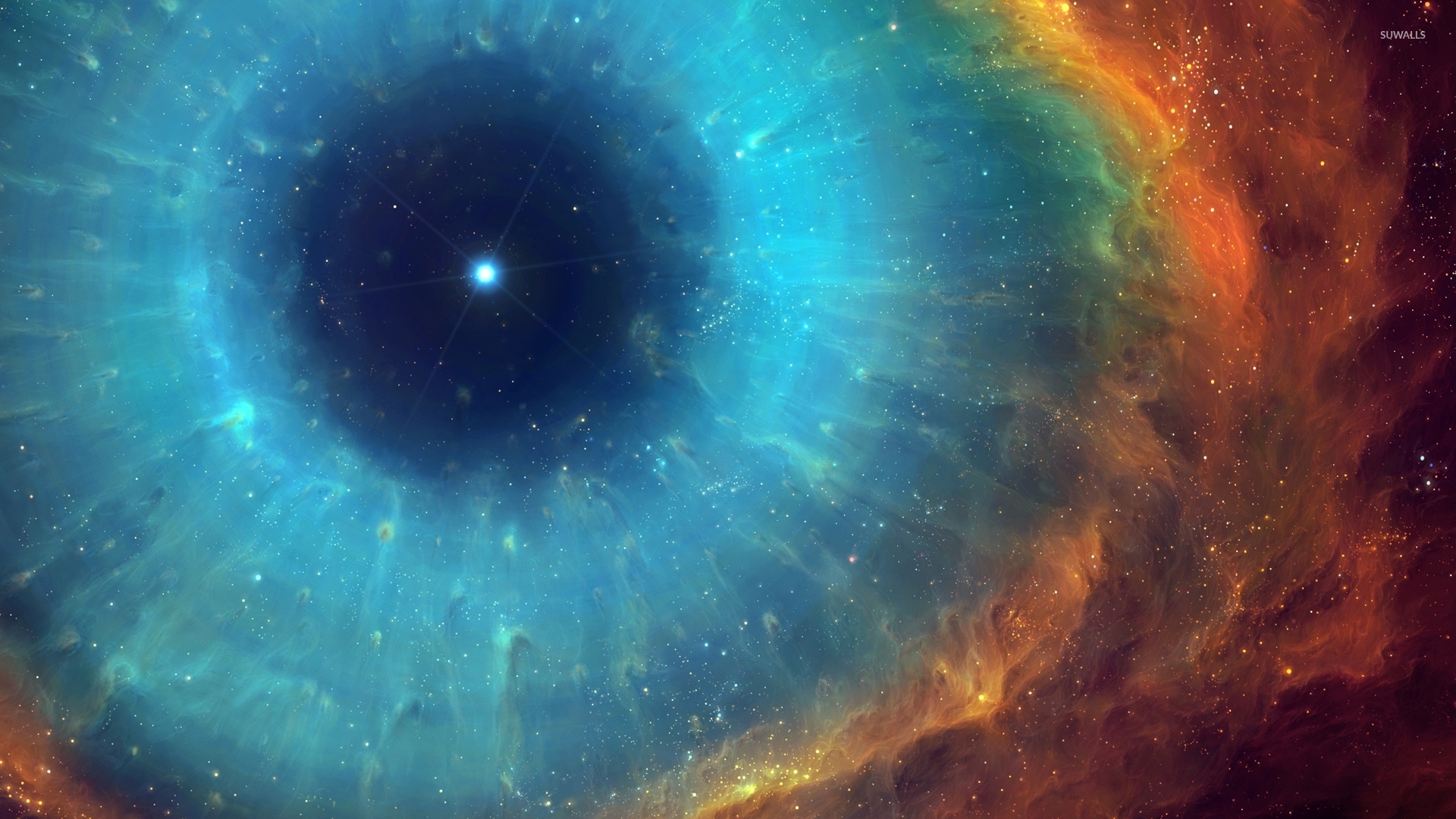

Look at it. Just for a second. It’s hard not to feel like something—or someone—is staring back at you from across the cosmos. That piercing blue "pupil" and the fleshy, red-rimmed lids are why the Helix Nebula earned its viral nickname: the Eye of God. But honestly, if you ask an astronomer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory or anyone working the graveyard shift at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), they’ll probably just call it NGC 7293. It's less poetic, sure, but it gets to the heart of what this thing actually is—a dying star gasping its last breath.

Space is weird. We try to find patterns in the chaos because a "cosmic eye" is easier to process than the terrifying reality of a star shedding its outer layers into a cold, indifferent vacuum.

What the Helix Nebula Actually Is (And Isn't)

Most people see the photos and think they’re looking at a static object. They aren't. You’re looking at a planetary nebula, which is a bit of a misnomer since it has absolutely nothing to do with planets. William Herschel started that trend back in the 1780s because, through his telescope, these roundish blobs looked like Uranus. The name stuck. It’s annoying, but that’s science history for you.

The Helix Nebula is basically a preview of our own sun's funeral. In about five billion years, our sun will run out of hydrogen, swell up into a red giant, and eventually cough out its outer shells. What’s left behind is a white dwarf. That tiny, incredibly dense white dot in the center of the "eye"? That’s the corpse of the star. It’s roughly the size of Earth but has the mass of a star. It’s so hot it glows in ultraviolet light, which ionizes the surrounding gas and makes the whole thing glow like a neon sign.

The Anatomy of the Eye

If you could fly through it, you wouldn't see an eye. You’d see a complex, multi-layered structure of gas and dust. We’re only seeing the "eye" shape because of our specific vantage point on Earth. We are looking down the barrel of a cylinder. If we were viewing it from the side, it would look completely different—likely more like a barbell or a butterfly.

- The Pupil: This is the inner region dominated by oxygen atoms, which glow blue when hit by intense UV radiation from the central star.

- The Iris: A transition zone where nitrogen and hydrogen dominate, creating those deep reds and oranges.

- Cometary Knots: This is where things get gnarly. If you look at high-resolution Hubble or VISTA images, you’ll see thousands of these "knots" that look like tiny comets with tails pointing away from the center. Each one is twice the size of our entire solar system. They’re formed by a "champagne flow" of hot gas pushing against cooler, denser gas.

Why the "Eye of God" Name Stuck

The internet loves a good mystery. In the early 2000s, an email chain letter—remember those?—started circulating with a low-res image of the Helix Nebula claiming it was a "miracle" photographed by NASA. It was total clickbait before we even had a word for clickbait. People were told to make a wish or share it for good luck.

While the religious connotations gave it staying power, the scientific community prefers the Helix because it describes the actual geometry. It’s a helix-shaped tube of gas. C. Robert O'Dell, an astronomer who has spent a massive chunk of his career studying the Helix with the Hubble Space Telescope, has pointed out that its complexity is staggering. It’s not just one shell; it’s at least two nearly perpendicular disks of gas.

🔗 Read more: Why Webb Space Telescope Pictures Still Keep Astronomers Up at Night

Seeing the Unseen: Infrared vs. Visible Light

When you see those vibrant, spooky photos, you’re often looking at a composite. The human eye can't see most of what’s happening in the Helix.

The VISTA telescope at the Paranal Observatory in Chile uses infrared light to peer through the dust. In visible light, the dust is opaque—it blocks the view. In infrared, the dust becomes transparent, revealing "cool" molecular hydrogen gas that looks like glowing cobwebs. It’s beautiful, but it’s also functional. Infrared allows us to map the distribution of matter and understand how the star is losing mass.

Basically, the Helix Nebula is a giant recycling center. The oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon being blown into space will eventually find their way into a new generation of stars and planets. Maybe even another "Earth" billions of years from now.

The Logistics of Finding It

If you have a decent pair of binoculars or a backyard telescope, you can actually see the Helix Nebula. It’s in the constellation Aquarius. But don't expect it to look like the Hubble photos. Through a small lens, it looks like a faint, greyish ghost of a donut. It’s huge—about half the size of the full moon—but its surface brightness is very low.

You need a dark sky. If you’re in a city with heavy light pollution, forget it. You’ll just be staring at a blank patch of sky. Wait for a moonless night in the autumn (if you’re in the Northern Hemisphere) and look low in the southern sky.

Why It Matters for Our Future

Studying the Helix isn't just about pretty pictures. It’s about destiny. Our sun is a middle-aged star. It’s roughly 4.6 billion years old. By studying the Helix Nebula, which is only about 10,000 years old (a blink in cosmic time), we are looking at our own future.

We see how the gas expands at roughly 31 kilometers per second. We see how the central white dwarf is cooling. We learn about the "enrichment" of the interstellar medium. Without planetary nebulae, there wouldn't be enough heavy elements in the universe to form rocky planets like ours. We are, quite literally, made of the stuff that stars like the Helix spit out when they die.

Actionable Steps for Stargazers and Space Fans

If you're fascinated by the Helix Nebula and want to dive deeper, don't just look at the memes. Here is how you can actually engage with this cosmic wonder.

1. Use WorldWide Telescope or Stellarium

Don't just look at static JPEGs. Download Stellarium (it's free and open-source) or use the WorldWide Telescope web interface. These tools allow you to zoom in on the Helix Nebula within the context of the entire sky. You can toggle between different wavelengths—visible, infrared, X-ray—to see how the "Eye" changes its appearance depending on the light spectrum.

✨ Don't miss: Math Intervals Explained: Why Those Tiny Brackets Actually Matter

2. Hunt for the "Ghost" Yourself

If you own a telescope, look for NGC 7293. Use an OIII (Oxygen III) filter. This filter blocks out almost all light except for the specific wavelength emitted by ionized oxygen. It makes the "pupil" of the eye pop against the dark background, even if you have some moderate light pollution.

3. Follow Real-Time Discoveries

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is constantly redefining what we know about stellar death. Check the STScI (Space Telescope Science Institute) newsroom regularly. While the Helix was a favorite for Hubble, newer infrared data from JWST is providing unprecedented detail on the molecular knots within the nebula.

4. Check Your Local Planetarium

Most major cities have planetariums that run shows specifically about the life cycle of stars. These shows often use the Helix Nebula as the primary visual example of a planetary nebula. Seeing it projected on a 360-degree dome is the closest you'll ever get to floating inside it.

The Helix Nebula isn't a mystical omen or a literal eye watching us. It’s something much more profound: a witness to the end of a star and a provider for the beginning of whatever comes next. It’s a reminder that in the universe, nothing is ever truly lost—it’s just rearranged.