You’re standing in the doctor's office. The nurse slides that cold metal bar down until it thumps onto your head, scribbles a number, and then makes you step on the scale. Then comes the "the talk." They pull out a height age weight chart and tell you exactly where you fall. It feels a bit like being graded on a curve you never signed up for. But honestly, most of those charts we see taped to office walls are actually based on data that is decades old. We’re obsessed with these numbers. We want to know if we're "normal."

But "normal" is a moving target.

👉 See also: Using Zilactin for Lie Bumps: Does It Actually Work?

Back in the day, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company basically invented the modern obsession with these charts. In 1943, they released tables based on "desirable weights." It wasn't even about health, really. It was about risk. They wanted to know who was likely to live longer so they could price their insurance policies better. Fast forward to now, and we’re still using variations of these metrics—like the Body Mass Index (BMI)—to judge our health at a glance. It's fast. It's easy. But is it actually accurate for you? Probably not as much as you'd think.

Why Your Height Age Weight Chart Might Be Lying to You

The biggest problem with a standard height age weight chart is that it’s a blunt instrument. It sees a pound of lead and a pound of feathers as the exact same thing. In human terms? It can't tell the difference between five pounds of muscle and five pounds of visceral fat.

Take a look at professional athletes. A running back in the NFL might stand 5'10" and weigh 220 pounds. If you plug that into a standard chart, the red flags start waving. It would label him as "obese." But his body fat percentage might be in the single digits. On the flip side, you have "skinny fat" individuals—people who look lean but carry dangerous amounts of fat around their internal organs. Their weight looks "perfect" on the chart, but their metabolic health is a mess.

We also have to talk about age. Your body at 20 is not your body at 60. As we get older, we lose bone density and muscle mass—a process called sarcopenia. If you’re 70 years old and trying to maintain the same weight you had at 25, you might actually be doing yourself a disservice. Research, including studies cited by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), suggests that for older adults, carrying a little extra weight can actually be protective against falls and wasting diseases.

Decoding the Numbers for Kids and Teens

When it comes to children, the height age weight chart changes completely. We don't use static numbers; we use percentiles. If a pediatrician says a child is in the 50th percentile, it just means they are right in the middle of the pack.

Growth spurts are chaotic. One month a kid looks like a beanpole, the next they’ve filled out, and then they shoot up three inches over the summer. Because of this, a single data point on a chart is basically useless. Doctors look for "growth curves." They want to see that the child is following their own consistent path. If a kid drops from the 80th percentile to the 20th, that’s when people start asking questions.

It’s also worth noting that puberty happens at wildly different times. A 13-year-old who hit puberty early will have a completely different height-to-weight ratio than a "late bloomer." Comparing them using the same rigid chart often leads to unnecessary body image anxiety.

The Role of Ethnicity and Genetics

Most of the charts used in Western medicine were originally calibrated using data from primarily Caucasian populations. This is a massive oversight.

📖 Related: Sore Throat: What To Do When It Actually Hurts To Swallow

Science has shown that body composition varies significantly across different ethnic groups. For example, research indicates that individuals of Asian descent may face higher risks for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease at a lower BMI than Caucasians. Meanwhile, some studies suggest that African Americans may have higher bone mineral density and muscle mass, meaning a "higher" weight on the chart doesn't necessarily carry the same health risks.

Genetics also play a role in where you store fat. Two people can be the same height and weight, but if one stores fat in their hips (subcutaneous) and the other stores it in their abdomen (visceral), their health profiles are worlds apart. Abdominal fat is metabolically active and linked to heart disease. The chart doesn't see that. It just sees the total number on the scale.

Better Ways to Measure Progress

If the height age weight chart is so flawed, what should we actually look at?

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR): This is often way more telling than weight. Grab a tape measure. Measure your waist at the narrowest point and your hips at the widest. Divide the waist by the hip. A lower ratio generally means less visceral fat.

- Body Fat Percentage: This distinguishes between the weight of your bones, muscles, and fat. You can get this measured via DEXA scans (the gold standard), skinfold calipers, or even some high-end smart scales (though those are less precise).

- Blood Markers: Honestly, your cholesterol, A1C (blood sugar), and blood pressure levels tell a much deeper story about your health than a scale ever could.

- Physical Capability: Can you walk up three flights of stairs without getting winded? Can you carry your groceries? Functional fitness is a huge indicator of longevity.

How to Actually Use a Chart Without Obsessing

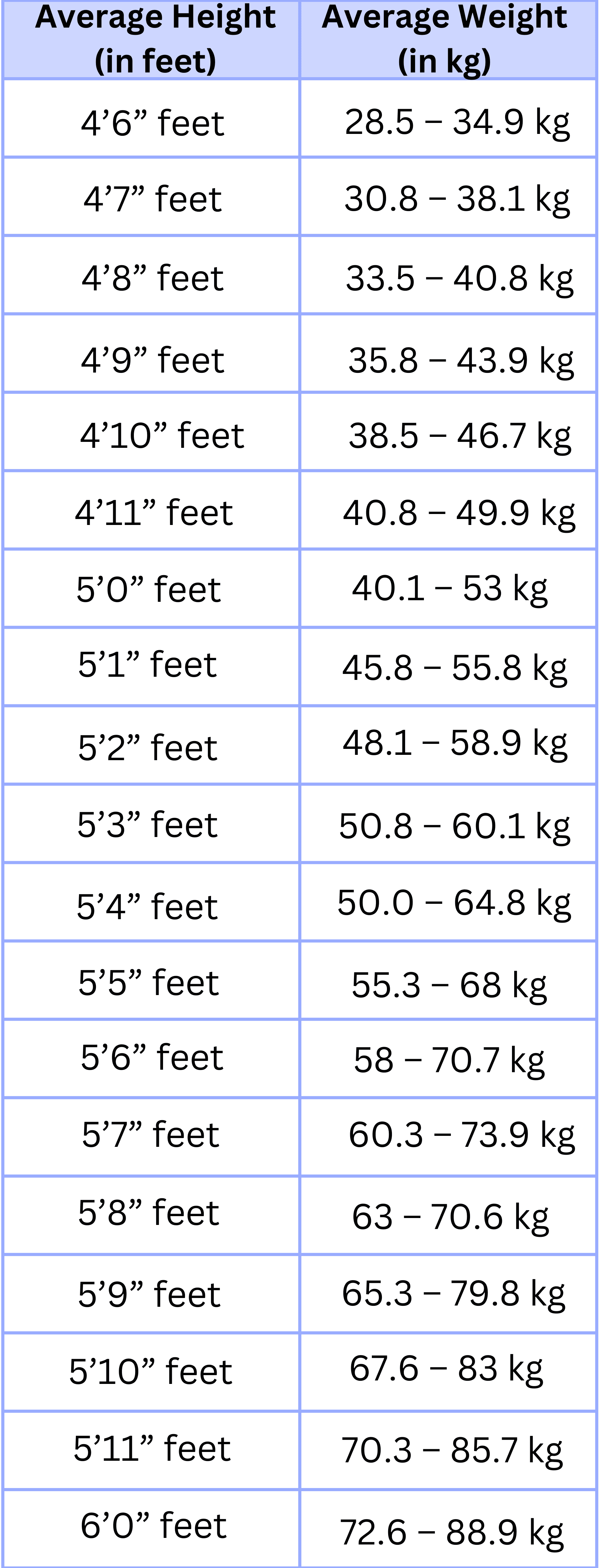

Look, these charts aren't totally useless. They provide a "neighborhood" for where you might want to be. If you are 5'5" and the chart says the healthy range is 114 to 150 pounds, and you weigh 250, the chart is telling you something real about your strain on your joints and heart.

But don't treat the number as a moral judgment. Use it as one single data point among dozens of others.

Check the date on the chart you're looking at. Is it the CDC's latest growth chart? Is it the WHO's international standard? Different organizations have different "cut-offs." For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) both use BMI, but they acknowledge that these are "population-level" tools, not meant to be a sole diagnostic for an individual.

Practical Steps for Your Next Check-up

Instead of just looking at the height age weight chart and feeling discouraged, take these steps to get a clearer picture of your health.

- Ask for a Waist Circumference Measurement: If your doctor doesn't do this, ask them to. For men, a waist over 40 inches and for women, over 35 inches, can indicate higher health risks regardless of what the weight says.

- Track Trends, Not Days: Weight fluctuates by 2-5 pounds a day just based on water and salt intake. Only look at the average over months.

- Focus on Body Composition: If you’re lifting weights, you might gain weight while losing inches. That is a massive win, even if the "chart" says you’re moving in the wrong direction.

- Discuss Your Specific Heritage: Talk to your healthcare provider about how your ethnic background might influence your "ideal" weight range.

- Prioritize Sleep and Stress: These factors influence weight more than people realize by messing with cortisol levels. If your weight is "off" on the chart, look at your lifestyle holistically.

The reality is that health is messy and complicated. A paper chart from 1995 can't capture the nuance of your life, your muscle mass, or your genetic history. Use the numbers as a guide, but trust your body’s performance and your lab work more than the scale.