When you picture the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map, you probably imagine a dusty parchment with dotted lines and big red "X" marks over safe houses. It makes sense. We love maps. They give us a sense of order in the chaos of history. But honestly? That map doesn't exist. Not in the way we think it does.

If Harriet Tubman had carried a physical map, she’d have been dead within a week. Carrying a drawing of secret routes through the Choptank River or the marshes of Dorchester County was a literal death warrant for a Black woman in the 1850s. Instead, her "map" was a masterclass in environmental science, celestial navigation, and psychological warfare. She memorized every jagged creek and every leaning tree.

The Invisible Geography of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Map

What we call a Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map today is actually a reconstruction by historians like Kate Clifford Larson, who wrote Bound for the Promised Land. These maps are modern attempts to visualize a ghost. Tubman operated primarily in the Eastern Shore of Maryland. This landscape is a labyrinth of brackish water and thick woods. It's beautiful, but it's also a nightmare to navigate at night while being hunted by men with dogs.

She didn't just walk north. That’s a common misconception. Sometimes she went south to throw off the scent. Sometimes she waited in a potato hole for days. Her "map" was composed of sensory data. She knew the sound of the wind through certain pines. She knew how the tide felt against her ankles in the marshes. This wasn't some casual stroll; it was a high-stakes chess game where the board was the earth itself.

The Big Dipper and the North Star

The most famous part of her navigation system was the Gourd. The "Drinking Gourd," or the Big Dipper. It's a cliché now, but for Tubman, it was her primary compass. By finding the two stars at the end of the Big Dipper’s bowl, she could locate Polaris, the North Star. This was her fixed point. As long as she moved toward that light, she was moving toward Pennsylvania, Delaware, or eventually, St. Catharines in Canada.

But stars get covered by clouds. What then?

🔗 Read more: Baba au Rhum Recipe: Why Most Home Bakers Fail at This French Classic

Tubman looked at the trees. She looked for moss. Now, you’ve probably heard that moss only grows on the north side of trees. That’s actually a bit of a myth—moss grows wherever it's damp. But Tubman knew the specific types of moss and the density of bark that indicated the northern side of a trunk in the Maryland woods. She was a naturalist before the term was popular. She understood the ecology of the South better than the people who claimed to own it.

Why the "Map" Kept Shifting

The routes were never static. If a safe house was burned or a "station master" was arrested, the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map had to be rewritten in her mind instantly. She used a network of Black and white activists, including the legendary Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware. Garrett was a Quaker who helped thousands. When Tubman reached his house, the "map" became slightly easier, but the danger never stopped.

There’s a reason she was called "Moses." She had this almost supernatural ability to sense danger. Some people attribute this to the head injury she suffered as a teenager—a heavy weight thrown by an overseer that caused her to have seizures and vivid dreams for the rest of her life. She believed these were premonitions from God. Whether you believe in the divine or the subconscious, those "visions" dictated the map. If she felt a "check" in her spirit about a certain path, she turned around. She never lost a single passenger. Not one.

The Real Cost of the Journey

Think about the physical toll. These journeys were often 90 to 140 miles. On foot. In the winter. Tubman preferred winter because the nights were longer and people stayed indoors. The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map wasn't just about geography; it was about timing. You had to move when the world was asleep.

She often started her escapes on Saturdays. Why? Because newspapers didn't print on Sundays. This gave her a 24-hour head start before runaway notices could be posted. That’s a brilliant tactical move that has nothing to do with terrain and everything to do with social engineering.

💡 You might also like: Aussie Oi Oi Oi: How One Chant Became Australia's Unofficial National Anthem

Modern Reconstructions and Where to See Them

If you actually want to see a Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map today, you should look at the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Maryland. They’ve done incredible work mapping out the specific sites of her life and her rescues.

- Stewart’s Canal: This was a massive public works project built by enslaved labor. Tubman used the traffic and the waterways here to move people and information.

- Bucktown General Store: The site of her traumatic head injury, but also a hub for news and movement.

- The Choptank River: A major artery for her travel.

These locations form the skeleton of the routes she took between 1850 and 1860. It wasn't one single line. It was a web.

The Canadian Connection

After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the "map" had to extend all the way to Canada. Northern states weren't safe anymore. Marshals could grab anyone and send them south on a whim. Tubman started taking her passengers across the bridge at Niagara Falls.

She lived in St. Catharines, Ontario, for a time. When she crossed that border, the map finally ended. The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map was effectively a bridge between two worlds: one where she was property, and one where she was a person.

Using This History Today

Understanding the "map" is about more than just history. It’s about resilience. It’s about how one person used limited resources and deep environmental knowledge to dismantle a massive system of oppression.

📖 Related: Ariana Grande Blue Cloud Perfume: What Most People Get Wrong

If you’re looking to explore this deeper, here is what you should actually do:

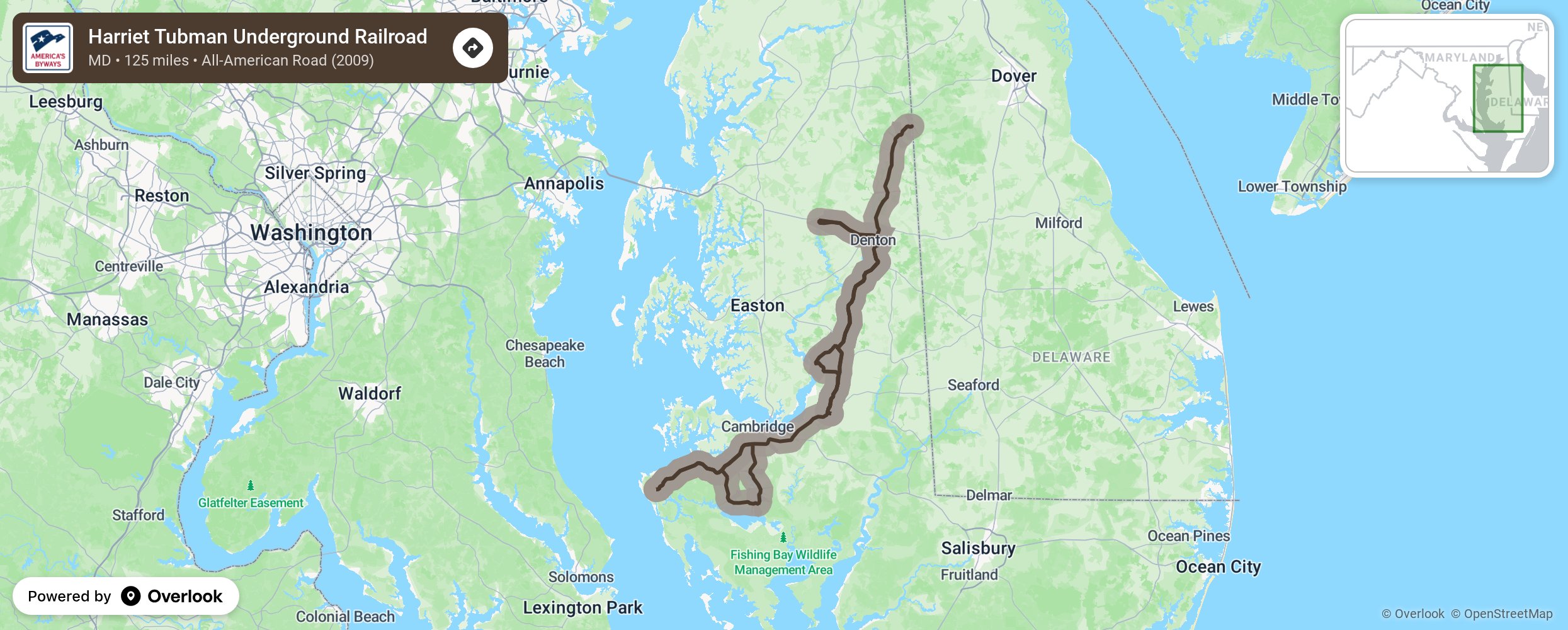

Visit the Byway.

Don't just look at a digital map. Drive the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Byway in Maryland and Delaware. It covers 125 miles and includes 36 sites. You need to see the height of the marsh grass and the density of the woods to understand why her navigation was so impressive.

Read the primary sources.

Check out the records of William Still. He was a Black abolitionist in Philadelphia who kept meticulous records of the people who passed through his station. He interviewed Tubman and the people she rescued. His book, The Underground Railroad, is the closest thing we have to a contemporary map of the souls she saved.

Support the preservation of these sites.

Many of the original safe houses and landscapes are threatened by development or rising sea levels in the Chesapeake Bay. Groups like the Network to Freedom (run by the National Park Service) work to certify and protect these locations.

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad map was never a piece of paper. It was a combination of starlight, moss, courage, and a genius-level memory. She didn't need a compass because she was the compass. Her legacy isn't just the path she took, but the fact that she went back, time and time again, to show others the way. That is the kind of map that never fades.