Names are heavy. Honestly, in Gilead, they’re weapons. If you’ve ever watched the show or read Margaret Atwood’s original 1985 novel, you know the chill that sets in when a woman is called "Offred." It isn’t just a label. It’s a cage.

Basically, the Handmaid's Tale names work as a system of erasure. You aren't a person; you're a bucket. A vessel. Property. When the regime strips a woman of her "shining name"—as the narrator calls her real identity—they aren't just being mean. They are deleting her history.

Why the "Of" Prefix is More Than Just Grammar

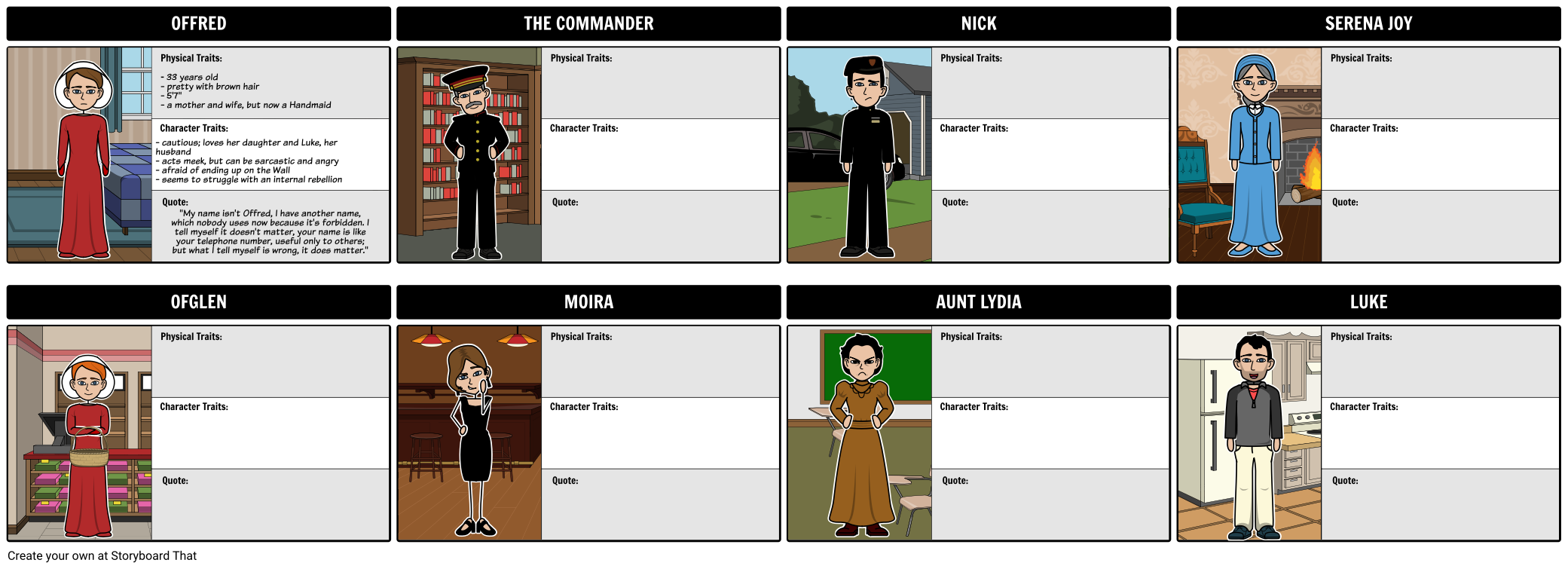

The most famous names in the story follow a rigid, possessive formula. Offred. Ofglen. Ofwarren.

It’s a patronymic. Think of it like a dark version of "Johnson" (son of John). In Gilead, the "Of" plus the Commander's first name—Fred, Glen, Warren—denotes total ownership. It’s "Of-Fred." He owns the house, he owns the garden, and he owns the woman meant to bear his children.

But there’s a layer many people miss.

Atwood has often mentioned that Offred also sounds like "offered." It’s a pun. She is a sacrifice. She’s being offered up on the altar of a dying society’s desperate need for babies. If you say it fast, it also sounds like "of red," the color of the blood-red habits the Handmaids are forced to wear.

The name changes whenever the Handmaid is moved. When the original Ofglen (played by Alexis Bledel in the series) is taken away, a new woman simply slides into the title. The name stays; the person is disposable.

👉 See also: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

The Mystery of June: Is It Canon?

Here is where fans get into heated debates at book clubs. Is her name June?

In the book, the narrator never explicitly says, "My name is June." She tells us she has a name she keeps hidden, a name that acts as a bridge to her past. But she never whispers it to the reader.

However, in the very first chapter, the women in the Red Center whisper names across their beds: "Alma. Janine. Dolores. Moira. June."

By the end of the book, every name on that list has been attached to a specific character except for one. June. Readers did the math. They decided, "Okay, the narrator must be June."

Margaret Atwood actually said she didn’t intend for that to be the "secret" answer, but she liked the fan theory so much that she rolled with it. When the Hulu series started, they made it official. June Osborne became the face of the rebellion. But if you're a book purist, she's still technically nameless.

Irony and Domestic Products: The Aunts and Wives

The naming conventions don't stop at the Handmaids. The elite women and the enforcers have their own brand of weirdness.

✨ Don't miss: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

Serena Joy is the ultimate irony. There is nothing serene about her, and she hasn't felt joy in a decade. She’s a former gospel singer and "traditional values" advocate who helped build the very cage she's now trapped in. Her name feels like a relic of the 1980s televangelist era—saccharine and fake.

Then you have the Aunts.

In the "Historical Notes" at the end of the novel, it’s revealed that the Aunts—Lydia, Elizabeth, Helena—were named after commercial domestic products. Aunt Lydia? Probably a nod to Lydia Pinkham’s vegetable compound, a famous 19th-century "woman’s tonic." Aunt Elizabeth? Elizabeth Arden.

The regime took names associated with female care and beauty and slapped them onto the women who use cattle prods to keep girls in line. It's a "kindly" mask for a brutal role.

The Martha's Biblical Roots

The Marthas, the women who do the cooking and cleaning, get their title from the Bible. In the Gospel of Luke, Martha is the sister who is "cumbered about much serving" while her sister Mary sits and listens to Jesus.

In Gilead, there are no "Marys" among the servant class. There are only Marthas. They are defined by their labor, their utility in the kitchen, and their invisibility.

🔗 Read more: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

The Men Get to Keep Their Names (Mostly)

Notice something? The men don’t lose their identities. Commander Fred Waterford. Nick Blaine. Luke.

They retain their surnames. They have histories. Even the "Angels" and "Guardians" are titles that imply power or protection, rather than subservience. The only time a man's name is manipulated is when it’s used to brand a Handmaid.

Nick is an interesting case, though. He’s a "Guardian," but his name is short, informal. It’s one of the few names in the book that feels "normal," which might be why the narrator feels she can trust him. Names in Gilead are usually either a rank or a brand. A simple first name feels like a radical act of intimacy.

What This Means for You

If you’re writing about the series or just trying to understand the subtext, remember that naming is an act of power.

When June insists on being called June, she’s committing a crime against the state. She’s saying, "I am not of anyone."

If you want to dive deeper into this, pay attention to the "Historical Notes" section of the book. It’s a transcript from a symposium in the year 2195. Even then, the male historians are more interested in identifying the Commander (Fred) than they are in finding the real name of the woman who actually told the story.

The erasure continues long after the regime falls.

Next Steps for Fans and Researchers:

- Re-read Chapter 1 of the novel and track every name mentioned to see how they reappear.

- Compare the "Historical Notes" at the end of the book to the series finale to see how the "legacy" of these names changes.

- Look into the etymology of "Gilead" itself—it’s a place of healing in the Bible, but a place of trauma in the story.