It started with a weird smell. In the summer of 1845, farmers across Ireland noticed a heavy, sweetish odor of decay wafting off their fields. One day the crops looked lush; the next, the leaves were blackened shriveled messes. When they dug into the earth, they didn’t find food. They found a black, slimy mush. This was the beginning of the Great Potato Famine of Ireland, a catastrophe that didn't just change Irish history—it fundamentally rewired the demographics of the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada.

Honestly, calling it just a "famine" is a bit of a simplification that makes some historians pretty uncomfortable.

The fungus-like organism responsible was Phytophthora infestans. It hitched a ride across the Atlantic from North America, likely on cargo ships. But the biology of the blight is only half the story. You've got to understand that by the 1840s, almost half the Irish population—especially the rural poor—was almost entirely dependent on a single crop: the Lumper potato. It was productive. It grew in poor soil. It fed families. But relying on one genetic variety meant that when the blight hit, there was no backup plan. No "Plan B." Just hunger.

Why Ireland was a Powder Keg Before the Blight

To understand the Great Potato Famine of Ireland, you have to look at the land. It wasn't just bad luck. It was a systemic collapse. Most of the land was owned by an Anglo-Irish Protestant gentry, many of whom didn't even live in Ireland. These "absentee landlords" used middlemen to sub-let tiny patches of land to Catholic tenant farmers.

These plots were tiny. We're talking barely enough space to sustain a family. Because the land was so subdivided, the only thing that could produce enough calories to keep a family of six or eight alive was the potato. It’s actually kind of wild when you look at the nutrition—a diet of potatoes and buttermilk is surprisingly complete. But it’s a precarious way to live.

British policy at the time was heavily influenced by "laissez-faire" economics. Basically, the idea was that the government shouldn't interfere with the market. Charles Trevelyan, the civil servant in charge of relief, famously viewed the famine through a pretty harsh providential lens. He sort of saw it as a mechanism to reduce the population and modernize the economy. That's a hard pill to swallow when people are starving in the ditches.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

While people were dying, Ireland was actually exporting food. This is the part that gets people heated. Huge quantities of butter, grain, and livestock were being shipped out of Irish ports to England because the "market" dictated it. The poor couldn't afford to buy the food they were raising for their landlords. It’s one of the most tragic examples of economic theory clashing with human survival.

The Reality of the Workhouses and "Soup Kitchen" Relief

By 1846 and 1847—often called "Black '47"—the situation went from bad to apocalyptic. The British government eventually set up workhouses. They were designed to be as miserable as possible to discourage "dependency." You had to be literally destitute to get in. Families were split up: men in one wing, women in another, children somewhere else.

Diseases like typhus and "famine fever" (relapsing fever) actually killed more people than actual starvation did. When you cram thousands of malnourished people into unsanitary stone buildings, it’s a death sentence.

Public Works and the "Roads to Nowhere"

The government tried to make people work for food. They started massive public works projects. You'll still see "famine roads" in Ireland today—roads that lead to the middle of nowhere or up the side of a mountain. Men who were already skeletal were forced to break stones in the rain to earn a few pence for Indian meal (maize). The maize was hard to digest and often caused agonizing intestinal issues because the people didn't know how to cook it properly.

The Quaker Contribution

Interestingly, the most effective relief often came from private charities. The Society of Friends, or Quakers, set up soup kitchens long before the government did. They saw the humanity in the victims when the official bureaucracy just saw "surplus population." They distributed "Soyer’s Soup"—a recipe created by a famous French chef, Alexis Soyer—which was intended to be a cheap, nutritious fix. It wasn't enough, but it saved thousands.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

The Coffin Ships and the Great Migration

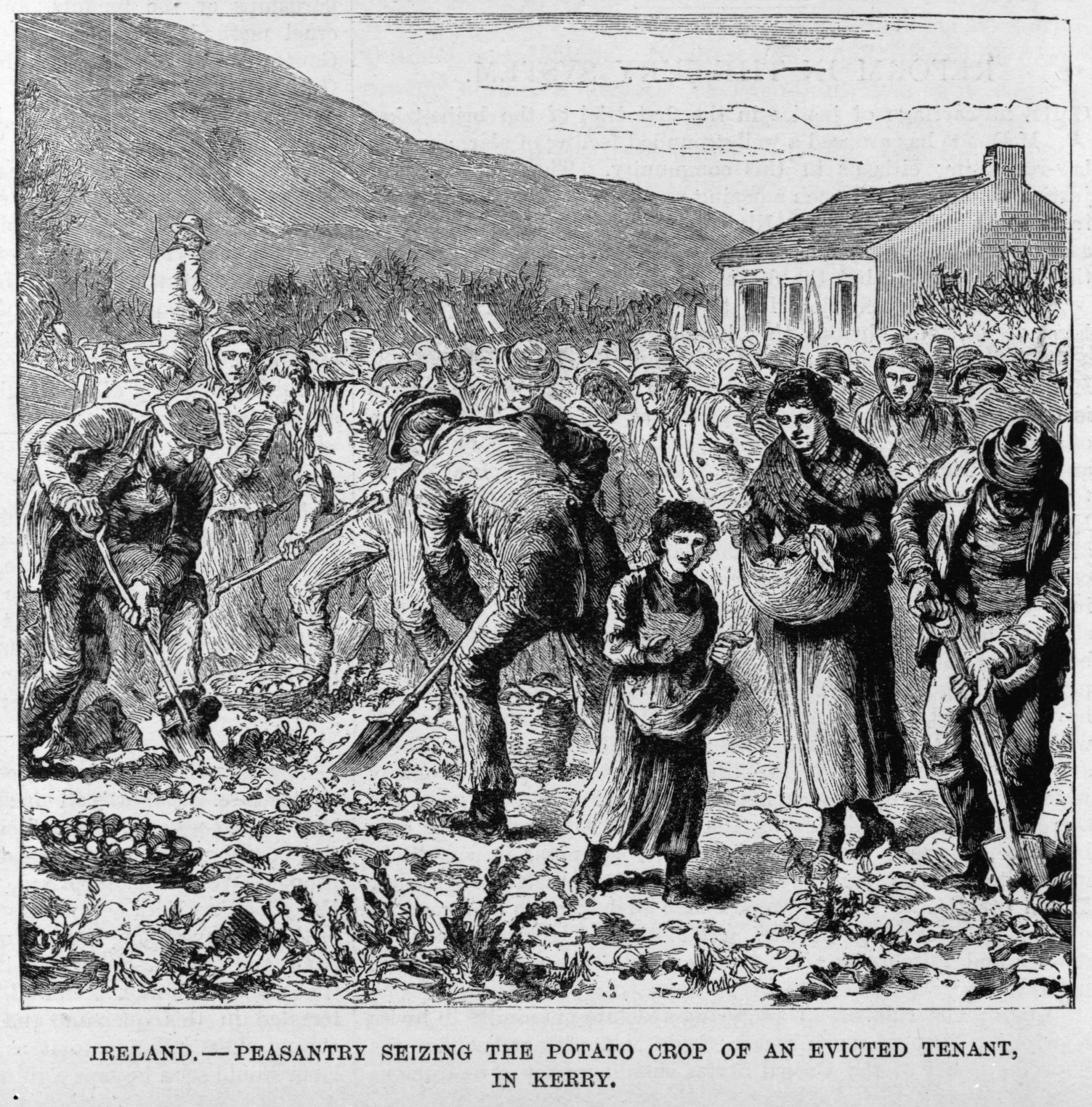

If you couldn't eat and you couldn't pay rent, you were evicted. Landlords would "tumble" the cottages—basically pulling the roof off so the tenants couldn't come back. This led to a mass exodus. Between 1845 and 1855, at least 1.5 million people fled Ireland.

They boarded "coffin ships."

That’s not a metaphor. These were often old cargo vessels that weren't meant for passengers. Mortality rates on some of these crossings were 20% or higher. If you survived the Atlantic, you landed in Grosse Île in Canada or New York City, usually with nothing but the clothes on your back and a deep-seated resentment of the British Crown.

This migration changed the world. It’s why there are more people of Irish descent in America than there are in Ireland today. It’s why St. Patrick’s Day is a massive global event. It’s also why Irish political machines became so powerful in cities like Boston and New York; these immigrants had a "never again" mentality born from the trauma of the Great Potato Famine of Ireland.

The Long-Term Impact on the Irish Language and Culture

Before the famine, Ireland was a powerhouse of the Irish language (Gaeilge). The west of the country, where the famine hit hardest, was the heartland of the language. When those communities were wiped out or forced to emigrate, the language took a hit it still hasn't fully recovered from. English became the language of survival, the language of the "New World."

📖 Related: Williams Sonoma Deer Park IL: What Most People Get Wrong About This Kitchen Icon

The famine also changed the Irish psyche. It created a culture of "late marriage" and a strange relationship with the land. It solidified the Catholic Church’s role as the central pillar of Irish identity, as the priests were often the only leaders who stayed with the people during the worst of the hunger.

Was it Genocide?

This is a massive point of debate. Most academic historians don't use the word "genocide" because there wasn't a conscious, state-level plan to exterminate the Irish people. However, they almost all agree that the British response was "genocidal" in its negligence. The refusal to stop food exports and the insistence on making starving people work for food was a choice. A choice that led to the death of about one million people.

Actionable Steps for Understanding Irish Heritage

If you're researching the Great Potato Famine of Ireland because of family history or general interest, there are specific things you can do to get a clearer picture of what happened.

- Visit the National Famine Museum at Strokestown Park. It’s located in County Roscommon and is built on the site of a major estate. They have the "Strokestown Papers," which are actual records of evictions and letters from tenants. It’s gut-wrenching but necessary.

- Check the Great Famine Voices Archive. This is an incredible digital resource that records oral histories and family stories passed down through generations.

- Trace your ancestors through Griffith’s Valuation. This was a land survey done shortly after the famine (1847-1864). If your family left during the famine, this is often the first "paper trail" you’ll find for them in Ireland.

- Read "The Graves Are Walking" by John Kelly. If you want a deep, readable dive into the politics and the biology of the blight, this is the book. It’s way better than any textbook.

- Support modern food security initiatives. The best way to honor the victims of 1845 is to recognize that "famines" today are almost always man-made, just like the Irish one was. Organizations like Concern Worldwide (which has Irish roots) work on this specifically.

The famine wasn't just a natural disaster. It was a failure of empathy and a failure of policy. By looking at the specific stories of the people who lived through it—the soup kitchen workers, the terrified tenants, even the conflicted landlords—we get a much more honest view of history. It’s a messy, tragic, and deeply human story that still defines what it means to be Irish today.

To find specific records of relatives who may have emigrated during this period, start by searching the New York Emigrant Savings Bank records or the Boston Pilot "Missing Friends" advertisements, which were used by families trying to find loved ones lost in the chaos of the migration. For local Irish records, the Catholic Parish Registers available online via the National Library of Ireland are the most reliable way to pinpoint where a family lived before the blight forced them out.