It started with a spark. Just one. Thomas Farriner, the King’s baker on Pudding Lane, probably thought he’d damped down his oven for the night. He hadn't. By 1:00 AM on Sunday, September 2, his shop was an inferno. Most people think the Great London Fire 1666 was just some inevitable accident in a crowded city, but the reality is way more chaotic, political, and frankly, a bit of a disaster in leadership.

London back then was a tinderbox. We’re talking about timber-framed houses covered in pitch (essentially flammable goo) huddling over narrow alleys. It hadn't rained properly in months. A massive drought had sucked every bit of moisture out of the wood. When that fire jumped from the bakery to the starched-hay-filled stables at the Star Inn nearby, the city was basically done for. But nobody knew that yet.

The Mayor Who Went Back to Bed

You’d think the Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth, would have jumped into action. Nope. When he was woken up and told about the blaze, he looked at it and famously remarked that "a woman might piss it out." He actually went back to sleep. That’s not a joke; it’s recorded in the diaries of the time. Because he refused to authorize the pulling down of houses to create firebreaks—mostly because he was worried about who would pay for the rebuilding—the fire got a foothold it never let go of.

By the time the sun came up, the "Lumbering Devil," as some called it, was moving fast. The wind was blowing from the east, pushing the flames right into the heart of the city.

Why the Great London Fire 1666 Didn't Stop

London didn't have a fire brigade. Not really. They had "fire hooks" to pull down thatch and buckets that were basically useless against a wall of heat. The only real way to stop a fire like this was to blow up houses with gunpowder to create a gap the flames couldn't jump. But the Mayor was paralyzed by the legalities.

Samuel Pepys, a name you probably remember from history class, was the one who finally realized how bad things were. He took a boat down the Thames and saw the "extraordinary fire." Pepys didn't just watch; he went to the Tower of London and then to the King. He told Charles II that unless houses were pulled down, nothing would stop the fire. The King finally gave the order, bypassing the Mayor, but by then, the wind was howling.

✨ Don't miss: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

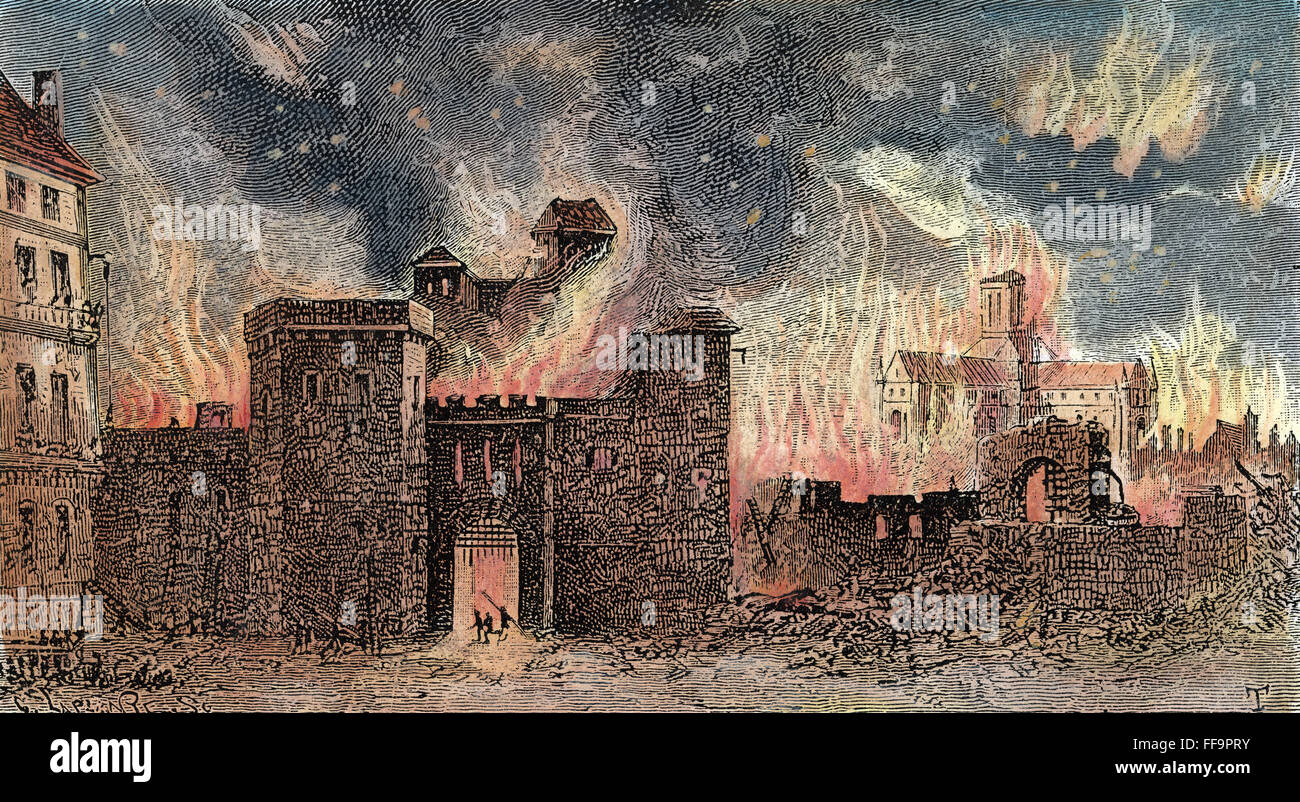

It’s hard to imagine the noise. 13,000 houses burning at once. The sound of timber cracking like gunshots. The sky turned a bruised, smoky orange that people could see from miles away.

The St. Paul’s Disaster

People thought St. Paul’s Cathedral was safe. It was made of stone, right? Huge open courtyards around it. It felt like a fortress. Because of this, everyone crammed their belongings inside. Booksellers from Paternoster Row stuffed the crypts with thousands of books, thinking the thick walls would protect their livelihood.

They were wrong.

The cathedral was undergoing renovations, which meant it was covered in wooden scaffolding. When the fire reached the roof, the scaffolding caught first. The heat got so intense—we’re talking over 1,000 degrees Celsius—that the lead on the roof started to melt. Pepys and other witnesses described "rivers of molten lead" flowing down the streets. The stones actually exploded from the heat. The books in the basement didn't stand a chance; they fueled the fire from the inside out until the whole structure collapsed.

Myths vs. Reality: The Death Toll

If you look at the official records from the time, the death toll for the Great London Fire 1666 is weirdly low. Only six deaths were officially recorded. Honestly? That’s almost certainly wrong.

🔗 Read more: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

While the fire moved slowly enough that most people could outrun it, the poor, the elderly, and the infirm likely didn't make it. The official count only tracked people of status. The intense heat would have cremated many victims completely, leaving nothing for the "searchers" of the dead to find. Modern historians like Neil Hanson have argued that the real death toll probably reached into the hundreds or even thousands, especially when you consider the respiratory issues and the harsh winter that followed for the newly homeless.

Searching for a Scapegoat

People couldn't just accept it was a baker's mistake. They wanted someone to blame. England was at war with the Dutch and the French, so naturally, rumors spread that it was a foreign plot. Mobs started attacking anyone who sounded like they had an accent.

A French watchmaker named Robert Hubert actually "confessed" to starting the fire. The guy was clearly mentally ill and wasn't even in London when the fire started—he arrived two days after it began—but the authorities hanged him anyway. They needed a win. They needed to tell the public that the "terrorists" had been caught. It’s a dark chapter of the story that often gets glossed over in kids' history books.

How the Fire Finally Died

By Wednesday, the wind finally dropped. The Duke of York (the King’s brother) had been leading the firefighting efforts on the ground, literally getting his hands dirty with the buckets and the gunpowder. By blowing up huge swathes of the city around the Temple and the Tower of London, they finally created enough of a gap.

The fire didn't just "go out." It smoldered for months. Even in December, people reported smoke rising from cellars when they tried to clear the rubble.

💡 You might also like: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

The Legacy of the Great London Fire 1666

London changed forever after that week. Before the fire, the city was a medieval maze of plague-ridden alleys. After? It became the brick and stone city we recognize today. Christopher Wren, the famous architect, didn't get to build his dream of a "Paris-style" city with wide boulevards because property owners refused to give up their original plots of land. But he did get to rebuild 51 churches, including the new St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The Fire Office was born, too. This was the start of the modern insurance industry. If you walk around London today, you might still see "fire marks"—metal plaques on old buildings. These told the private fire brigades that the building was insured. If your house didn't have one? They might just let it burn.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re heading to London to see the sites of the Great London Fire 1666, don’t just look at the postcards. Here is how to actually experience the history:

- Climb The Monument: It’s 202 feet tall. Why? Because that’s exactly how far it stands from the site of Thomas Farriner’s bakery on Pudding Lane. If you laid it down flat, the tip would touch the spot where the fire started.

- Visit the Museum of London Docklands: Since the main Museum of London is currently moving, check out their digital archives or specific fire exhibits at the Docklands site to see the "melted" objects found in the ash—glass bottles warped into strange shapes by the heat.

- Find the Golden Boy of Pye Corner: Everyone knows where the fire started, but go to Giltspur Street to see where it ended. There’s a small golden statue of a fat boy. The legend at the time was that the fire was a punishment from God for the "sin of gluttony," so it started at Pudding Lane and ended at Pye Corner.

- Check the Church Floors: If you go into the older City churches, look for uneven floorboards or charred wood in the crypts. St. Bride’s on Fleet Street has a great crypt museum that shows the layers of the city, including the burn layer from 1666.

The fire was a tragedy, sure. It destroyed 80% of the city. But it also ended the Great Plague by burning out the rat-infested slums. It forced London to modernize. It’s the reason the city feels the way it does today—a mix of high-tech glass and the stubborn, brick-built resilience of a city that refused to stay dead.

To understand London, you have to understand the ash it’s built on. The fire didn't just burn the city down; it cleared the way for the British Empire’s capital to rise. If you’re walking through the City today, look at the street names. Bread Street, Milk Street, Pudding Lane. They’re the ghosts of a medieval city that vanished in four days in September.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Read the unabridged version of Samuel Pepys’ Diary for September 1666. It is the most visceral, first-hand account available and captures the panic better than any textbook.

- Examine the 1667 Rebuilding Act documents online via the National Archives to see how the government regulated brick thickness and street widths to prevent a repeat disaster.

- Visit the Guildhall Library if you are in London; they hold the original surveys of the city made immediately after the fire.