October 1780 was a nightmare. While the American Revolution was busy tearing through the colonies, a monster was brewing in the Atlantic that didn't care about politics or independence. It’s still called the Great Hurricane of 1780. To this day, no other Atlantic hurricane has come close to its death toll. We are talking about 22,000 people dead. Minimum. Some estimates push that number even higher because, honestly, record-keeping in the 18th-century Caribbean was a mess.

It wasn't just a storm. It was a total wipeout of human life and infrastructure across the Lesser Antilles.

If you look at modern disasters like Katrina or Maria, they are horrific. But the Great Hurricane of 1780 happened in an era of wooden ships and stone huts. There was no satellite imagery. No "get out now" push notifications on a smartphone. Just a sudden, terrifying drop in the barometer and then the world ending.

What Actually Happened During the Great Hurricane of 1780?

The storm first made its presence felt around October 10th. Barbados took the first hit. It wasn't just a "bad storm." It was a complete leveling of the island. Reports from the time, including letters from the British Admiral Rodney, described how the wind was so violent it actually stripped the bark off the trees before snapping them like toothpicks.

Think about that for a second.

The wind wasn't just blowing things over; it was exfoliating the vegetation. Scientists today look at those accounts and estimate the wind speeds must have topped 200 miles per hour. That’s a Category 5 on steroids.

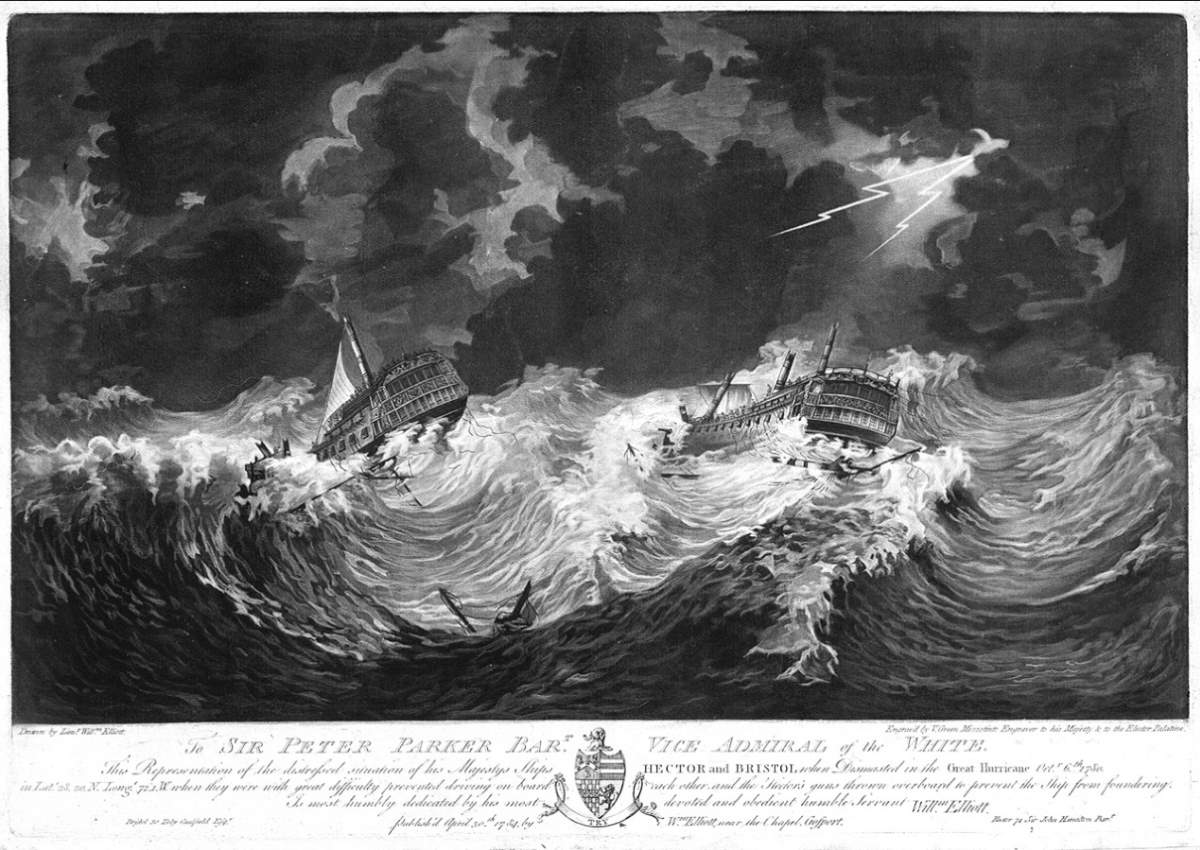

The hurricane then tracked its way toward Martinique and St. Eustatius. In Martinique, it’s estimated that 9,000 people died. Imagine a small island losing that many souls in a single afternoon. The French fleet, which was there to support the Americans against the British, was basically vaporized. Forty ships sank. Thousands of sailors drowned. The British didn't fare much better. They lost dozens of warships.

🔗 Read more: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

It’s one of those weird moments in history where nature just stepped in and hit the "pause" button on a major war.

Why was it so deadly?

It’s a mix of bad luck and bad timing. 1780 was a freak year for the Atlantic. This wasn't even the only storm that month. It was the second of three major hurricanes to hit in a three-week span. The ground was already saturated. People were already on edge.

Then you have the geography. The Lesser Antilles are sitting ducks. When a storm of this magnitude hits a small island, there is nowhere to run. You can’t drive inland. You just huddle in a cellar and hope the ocean doesn't come for you. In 1780, the ocean definitely came for them. The storm surge was reportedly 25 feet high in some places. It wiped out entire coastal villages in minutes.

Most people don't realize that the "Great Hurricane" wasn't just a wind event. It was a massive drowning event.

The Scientific Mystery of the 200 MPH Winds

Meteorologists like Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Jerry Jarrell have spent years trying to reconstruct the path and intensity of the Great Hurricane of 1780. Because we didn't have anemometers that could survive such a storm back then, we have to rely on "proxy data."

What is proxy data? Basically, it’s looking at the damage and working backward.

💡 You might also like: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

If a stone building with walls three feet thick is leveled to the ground, you can calculate the force required to do that. When you hear that the bark was stripped from trees, that tells a specific story. It means the wind was carrying so much debris—sand, salt, pieces of other trees—that it acted like a giant sandpaper belt. That only happens when winds stay consistently above 180-200 mph.

The Path of Destruction

- Barbados: Total devastation. Every single house was damaged or destroyed.

- Saint Vincent: 584 out of 600 houses were flattened.

- St. Lucia: A British fleet was caught in the harbor. Most were smashed against the rocks.

- Martinique: The town of Saint-Pierre was essentially erased.

The storm eventually curved north, passing near Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic before heading out into the North Atlantic. Even as it weakened, it was still causing shipwrecks as far north as the Grand Banks.

The Revolution Connection

You can't talk about this hurricane without talking about the American Revolutionary War. It’s one of the biggest "what ifs" in military history. Both the British and French navies were stationed in the Caribbean to protect their sugar colonies and launch attacks.

Admiral George Rodney wrote back to London that the wind was so loud people couldn't hear themselves screaming. He actually thought an earthquake had happened simultaneously because the ground was shaking so much from the force of the waves.

The British lost 13 ships of the line. The French lost even more. If this storm hadn't happened, the naval balance of power in the final years of the Revolution might have looked very different. It crippled the British Caribbean fleet right when they needed it most.

Misconceptions About 18th-Century Storms

People often think folks back then were "used to it." They weren't. You don't get used to this.

📖 Related: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

Another common myth is that the death tolls are exaggerated. If anything, they are likely undercounted. Enslaved populations on the sugar plantations were often not meticulously recorded in census data. When a hurricane leveled a plantation, the "official" death toll often prioritized the landowners and the merchant class. The true human cost among the enslaved African population in Barbados and Martinique was likely staggering and under-reported by thousands.

Also, people think these storms are getting worse because of modern technology. While climate change is making storms wetter and more intense on average, the Great Hurricane of 1780 proves that the earth is capable of generating absolute monsters entirely on its own. It serves as a baseline for the "worst-case scenario."

Lessons for Today

So, why does a storm from 245 years ago matter to you?

Because it sets the ceiling. When emergency managers talk about "the big one," they are looking at the Great Hurricane. It’s the proof that an Atlantic storm can, under the right conditions, kill tens of thousands of people in a localized area.

We live in a world of concrete and steel now, but our coastal density is a hundred times higher than it was in 1780. If a storm with 200 mph winds and a 25-foot surge hit the modern Caribbean or the Florida coast, the infrastructure might hold up better, but the sheer volume of people in harm's way is terrifying.

What you can actually do with this information

If you live in a hurricane-prone area, history is your best teacher. The 1780 event teaches us that the "unthinkable" is actually historically precedented.

- Don't rely on "it hasn't happened in my lifetime." The Great Hurricane was a 1-in-500-year event. Just because you haven't seen it doesn't mean the atmosphere isn't capable of it.

- Respect the surge. Most people who died in 1780 didn't die from wind. They drowned. If you are told to evacuate because of water, you go.

- Look at your home's "tree profile." The fact that bark was stripped in 1780 reminds us that trees become shrapnel in high winds. Keep your property clear of deadwood.

- Study the history of your specific region. If you live in the Lesser Antilles, know that your island has a "ghost" of 1780. Local topography often dictates where storm surges hit hardest.

The Great Hurricane of 1780 isn't just a footnote in a history book. It’s a warning. Nature doesn't care about our wars, our borders, or our technology. It just does what it does. And sometimes, what it does is change the course of history in a single, violent night.

To prepare for the future, you have to acknowledge how bad things have truly been in the past. Check your local flood maps, understand your evacuation zone, and never underestimate the power of a falling barometer.