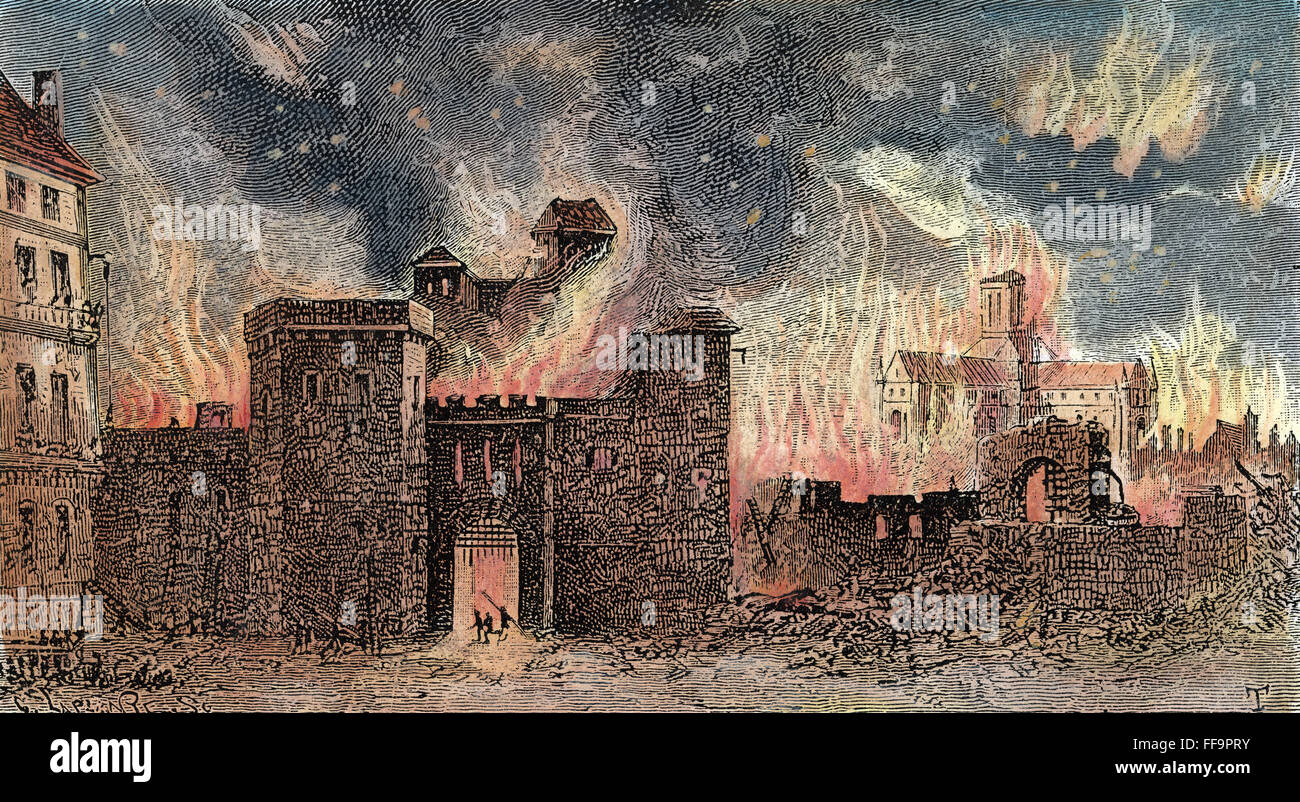

It started with a spark. Just one tiny, neglected ember in a baker’s oven on a cramped street near the Thames. Most people think of the Great Fire of London in 1666 as this sudden, cinematic explosion of flame that leveled the city in a heartbeat, but the reality was actually a lot more agonizing. It was slow. It was preventable. And honestly, it was kind of a miracle that the whole city didn't just stay a pile of ash forever.

London in the mid-17th century was a death trap. Imagine streets so narrow you could reach out of your top-floor window and shake hands with your neighbor across the way. The houses were mostly timber, coated in flammable pitch, and stuffed with hay, coal, and tallow. It was a tinderbox waiting for a match. When Thomas Farriner, the king’s baker, went to bed on Saturday night, September 1st, he thought his oven was out. He was wrong. By 2:00 AM on Sunday, his house on Pudding Lane was an inferno.

Why the Great Fire of London in 1666 Got Out of Control

The Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth, is basically the villain of this story, though maybe he was just overwhelmed. When he was first woken up to see the fire, he reportedly looked at it and said, "Pish! A woman might piss it out," and went back to sleep. That quote has lived in infamy for centuries. He didn't want to authorize the pulling down of houses—the standard way to create firebreaks—because he was worried about the cost of rebuilding them. By the time he realized the scale of the disaster, the wind had picked up.

A strong easterly gale was blowing. This wasn't just a fire; it was a "firestorm." The heat became so intense that it created its own weather system. It didn't just move from house to house. It leaped. Brands of burning wood flew hundreds of feet through the air, landing on thatched roofs and warehouses filled with oil, brandy, and brimstone down by the river.

People were panicked. You've probably heard of Samuel Pepys, the guy who kept the famous diary. His account is the reason we know so much about the vibe of the city. He describes people throwing their belongings into the river and even burying things in their gardens. Pepys himself buried a wheel of Parmesan cheese and some wine because they were his most prized possessions. It sounds funny now, but it shows how desperate things were. People weren't just losing houses; they were losing their entire livelihoods in a matter of hours.

The Geography of the Chaos

The fire moved west. It pushed toward the financial heart of the city and the great Gothic structure of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral. People thought the cathedral was safe. It was made of stone, right? Plus, it sat in a large open square. Booksellers from nearby Paternoster Row crammed the crypts with their inventory, thinking the thick walls would act as a safe.

✨ Don't miss: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

They were tragically wrong. The cathedral was undergoing repairs and was covered in wooden scaffolding. When the fire hit the scaffolding, the heat grew so intense that the lead on the roof—six acres of it—began to melt. Pepys and other witnesses described the lead running down the streets like a glowing river. The stone walls literally exploded from the heat. The "safe" books in the crypt acted as fuel, and the whole thing burned for days.

The Myth of the Low Death Toll

One of the weirdest things you’ll read in history books is that only six people died in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Let's be real: that's almost certainly nonsense.

The official count only tracked "recorded" deaths. This mostly meant middle-class or wealthy citizens. The thousands of poor Londoners, the laborers, the elderly, and the homeless? They weren't exactly being tracked by the bureaucracy of the time. When you consider that the fire reached temperatures of over 1,250°C, it’s highly likely that many victims were simply cremated. Nothing left to find. No body, no record. Modern historians like Neil Hanson have argued that the death toll was likely in the hundreds, if not thousands, when you factor in the respiratory issues and the subsequent winter spent in makeshift refugee camps on Moorfields.

- Sunday: The fire starts at Pudding Lane and spreads to the riverfront.

- Monday: The fire moves north and west, consuming the Royal Exchange and the high-end shopping districts.

- Tuesday: The most destructive day. St. Paul's is destroyed. The fire jumps the River Fleet toward Westminster.

- Wednesday: The wind finally drops. The use of gunpowder to blow up houses finally creates gaps the fire can't jump.

- Thursday: The flames are mostly extinguished, leaving a smoking skeleton of a city.

Turning the City into a Laboratory

While the fire was a humanitarian disaster, it gave London a chance to start over. It was basically the ultimate "urban renewal" project, though a very painful one. Before the embers were even cold, architects like Christopher Wren were handing King Charles II plans for a new city. Wren wanted a grid system with huge piazzas and wide boulevards, sort of like Paris or Rome.

🔗 Read more: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

He didn't get it.

The problem was property rights. Londoners were stubborn. They wanted their specific plot of land back exactly where it was. So, the city was rebuilt on the same messy, medieval street plan. However, the Rebuilding of London Act 1667 changed the "how" if not the "where." Brick and stone became mandatory. No more overhanging jetties that trapped heat and fire.

The Great Fire also birthed the modern insurance industry. Before 1666, if your house burned down, you were just broke. Afterward, Nicholas Barbon started the "Fire Office," the first fire insurance company. These companies actually had their own private fire brigades. If you had insurance, you’d nail a "fire mark" (a lead plaque) to the front of your house. If a fire started, the brigade would show up, look for the plaque, and if they didn't see theirs, they might just stand there and watch it burn while waiting for the right company to arrive. Sorta brutal, right?

The Scapegoat and the Truth

In the aftermath, people were angry and looking for someone to blame. They couldn't believe a baker’s oven caused all this. Rumors flew that it was a Catholic plot or a French/Dutch attack. A French watchmaker named Robert Hubert actually "confessed" to starting the fire as an agent of the Pope.

He was hanged.

💡 You might also like: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The catch? It was later proven he wasn't even in London when the fire started. He arrived two days after it began. But the public needed a head on a spike. It wasn't until 1986—over 300 years later—that the Worshipful Company of Bakers finally apologized for the fire, acknowledging that it was indeed Thomas Farriner’s faulty oven that did the deed.

What We Can Learn Today

The Great Fire of London in 1666 is more than just a date for history quizzes. It’s a case study in crisis management (or the lack thereof) and urban resilience.

It teaches us about the "cascading failure" of systems. The city’s water supply was primitive—wooden pipes that were actually cut by people trying to get water to save their own homes, which drained the pressure for everyone else. It shows how the delay in making a hard decision (like the Lord Mayor refusing to pull down houses) can lead to a catastrophe that costs a thousand times more than the initial sacrifice would have.

If you’re visiting London today, the traces are still there. You can climb the Monument—a massive Doric column designed by Wren and Robert Hooke. It’s exactly 202 feet tall, which is the exact distance from its base to the site of the bakery in Pudding Lane. If you stand at the top, you’re seeing a city that was forced to evolve through fire.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you want to truly understand the impact of the fire beyond the textbook, you should follow these steps:

- Visit the Museum of London: They have an incredible "Fire! Fire!" exhibition that uses archaeological finds—like melted pottery and charred keys—to show the heat's intensity.

- Walk the Monument: Don't just look at it. Climb the 311 steps. It gives you a physical sense of the scale and the proximity of the river.

- Check out the Golden Boy of Pye Corner: This is a small statue marking the spot where the fire finally stopped. Interestingly, the inscription suggests the fire was a punishment from God for the "sin of gluttony," because it started at Pudding Lane and ended at Pye Corner.

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just take a historian's word for it. Look up digital copies of the London Gazette from September 1666 or read Samuel Pepys' diary entries for that week. The fear in his writing is palpable.

The fire didn't just burn buildings; it burned away the last remnants of the plague, which had decimated the city the year before. It was a brutal, fiery reset button. London became a city of brick, a city of insurance, and a city of organized fire brigades—all because a baker forgot to rake his coals one Saturday night.