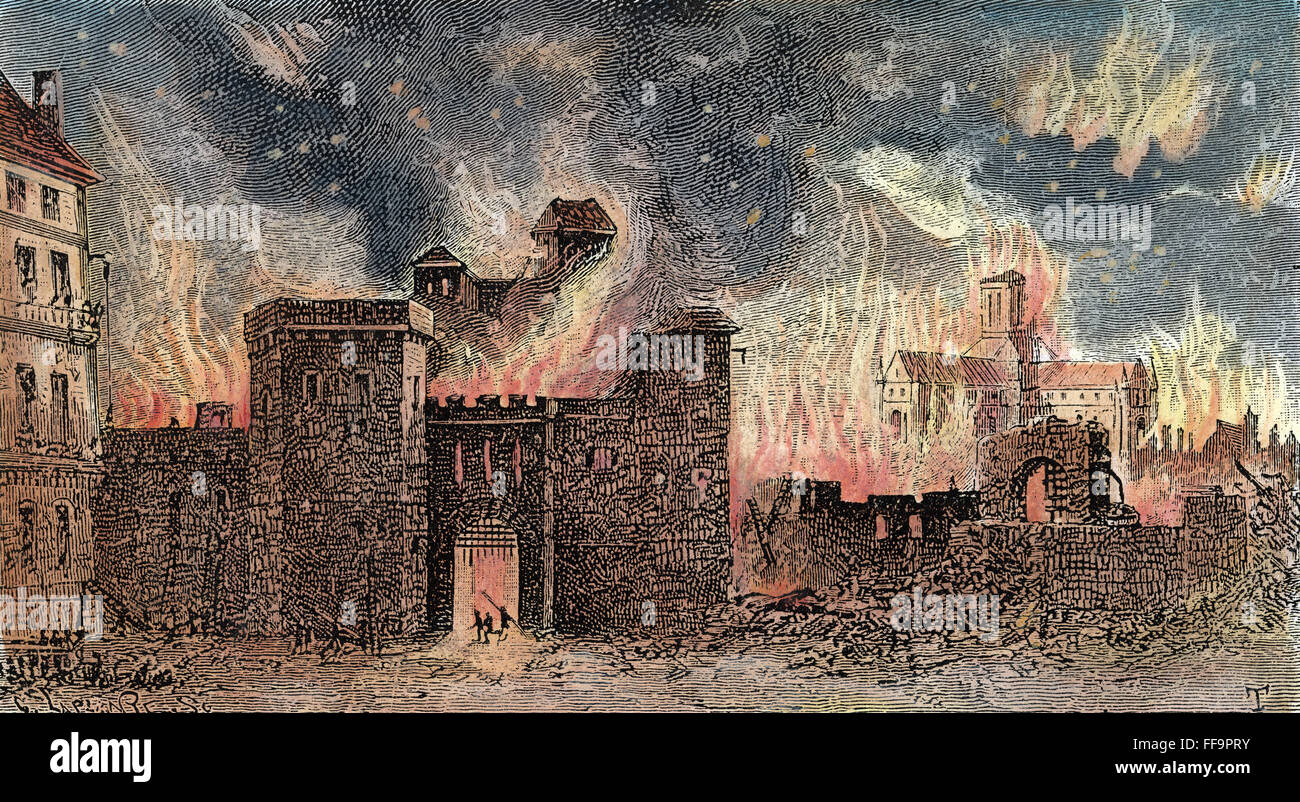

It started with a spark in a baker's oven on Pudding Lane. Honestly, that sounds like the beginning of a fable, but for the people living in the cramped, timber-framed mess of 17th-century London, it was the start of a literal hell on earth. We’ve all seen the woodcut illustrations of the Great Fire of London 1666, those jagged orange flames licking the sky while people flee in tiny rowboats. But the reality was way messier, way more political, and significantly more chaotic than your primary school history books probably let on.

Most people think the city just sat there and watched it burn. That's not true. They fought it with everything they had, which, unfortunately, wasn't much more than leather buckets and "fire hooks" meant to pull houses down before the flames could reach them. It was a disaster of urban planning as much as it was a freak accident.

Why the Great Fire of London 1666 was a Perfect Storm

You have to understand what London looked like in September 1666. It was a tinderbox. The summer had been brutally hot and dry, parching the oak and pine timbers of the overhanging houses. These buildings, called "jetties," leaned out over the narrow streets so far that neighbors in upper stories could practically shake hands across the road.

Then came the wind.

A strong easterly gale—what contemporaries called a "furious" wind—blew the sparks from Thomas Farriner’s bakery directly into the starched hay and tallow stored in nearby cellars. By the time the Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth, was woken up to look at it, he famously dismissed it with a vulgar comment about a woman being able to extinguish it with a certain bodily function. He was dead wrong.

By dawn, high street was a wall of flame. The fire didn't just move; it leaped. Because the houses were coated in pitch (basically flammable tar) to keep out the rain, they ignited instantly.

The Diary of Samuel Pepys and the Ground Truth

If we didn't have Samuel Pepys, we'd know a lot less about the human side of the Great Fire of London 1666. Pepys wasn't some dry historian; he was a government official who loved gossip, good food, and his dog. His diary entries from those four days are frantic. He describes burying his expensive Parmesan cheese and wine in the garden to save them from the heat.

People were desperate.

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

He saw "poor catts" with their fur singed off and people flinging their belongings into the River Thames. The river was the only escape for many. The heat was so intense that the lead roof of Old St Paul’s Cathedral—one of the largest structures in the world at the time—melted. Witnesses described the lead running down the streets like a glowing river. Think about that for a second. Stone and lead melting because of a bakery fire.

The Scapegoats and the "Terrorist" Narrative

Humans haven't changed much in 350 years. When something goes wrong, we look for someone to blame. Almost immediately, rumors started flying that the Great Fire of London 1666 wasn't an accident. England was at war with the Dutch and the French. Naturally, the terrified populace decided it must be a foreign plot.

They found a "confession" from a French watchmaker named Robert Hubert. He claimed he started the fire on behalf of the Pope. The poor guy was clearly mentally ill and hadn't even arrived in London until two days after the fire started, but the authorities hanged him anyway.

It was a total miscarriage of justice.

People were being attacked in the streets just for speaking with a foreign accent. This wasn't just a natural disaster; it was a period of intense social paranoia. The fire was eventually stopped not by fire engines—which were basically giant syringes on wheels that broke almost immediately—but by the Navy using gunpowder to blow up entire blocks of houses. They created "firebreaks." They had to destroy the city to save it.

The Shocking Death Toll Mystery

Here is something weird: the official death toll for the Great Fire of London 1666 is incredibly low. Traditionally, it was recorded that only about six to ten people died.

That is almost certainly total nonsense.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

While the "official" records only counted those who died in the immediate flames and were identifiable, they didn't account for the thousands of poor citizens whose bodies would have been completely cremated by the 1,250°C heat. Nor did they count the people who died in the makeshift refugee camps at Moorfields from exposure and respiratory issues in the months following. Modern historians like Adrian Tinniswood suggest the toll was likely in the hundreds, if not thousands, once you factor in the aftermath.

How the Fire Changed London Forever

The city that rose from the ashes didn't look like the old one. King Charles II saw an opportunity. He wanted a grand, Baroque city like Paris with wide boulevards. Christopher Wren, the famous architect, drew up these massive, sprawling plans.

But there was a problem: property rights.

Londoners are stubborn. They wanted their specific plots of land back. So, the "New London" ended up keeping the same messy street plan, but the buildings changed. The Rebuilding Act of 1667 mandated that all new houses be built of brick or stone. No more timber. No more thatched roofs. No more jetties overhanging the streets.

This is why, if you walk through the "City" (the financial district) today, you see those tiny, winding alleys but the buildings are all solid masonry. The fire literally baked the modern aesthetic of London into place.

The Birth of the Insurance Industry

We can also thank the Great Fire of London 1666 for your monthly insurance premiums. Before the fire, fire insurance didn't really exist. Afterward, Nicholas Barbon established "The Fire Office" in 1667.

Insurance companies even had their own private fire brigades. If your house was on fire, they’d look for a "fire mark" (a lead plaque) on your wall. If you weren't a customer, they might just stand there and watch your house burn while they protected the insured house next door. Brutal, right?

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

The Plague Myth

You've probably heard that the fire was a "blessing in disguise" because it killed the rats and ended the Great Plague of 1665.

It’s a neat story. It’s also largely a myth.

While the fire did destroy the filthy, rat-infested slums in the city center, the plague was already on the decline before September 1666. Furthermore, the fire didn't touch the poorest suburbs outside the city walls, which is where the plague was most rampant anyway. The disease died out for a variety of complex biological and environmental reasons, not just because a few bakeries burned down.

Understanding the Scale of the Loss

To wrap your head around what was lost in the Great Fire of London 1666, look at these numbers:

- 13,200 houses incinerated.

- 87 parish churches gone.

- 70,000 to 80,000 people made homeless out of a population of 600,000.

- £10 million in damages (in 1660s money, which is billions today).

The sheer scale of the displacement was unprecedented. For years, the city was a giant construction site. The smell of smoke reportedly hung in the air for months, and cellars were still smoldering as late as November.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you're interested in seeing the scars of the fire today, you don't have to look far.

- Visit The Monument: Standing 202 feet tall, it's located exactly 202 feet from where the fire started in Pudding Lane. If you climb the 311 steps, you get a sense of the geography the fire covered.

- The Golden Boy of Pye Corner: Most people go to the Monument, but head to Smithfield. There’s a small gilded statue of a fat boy. It marks the spot where the fire finally stopped. The inscription suggests the fire was a punishment for the sin of "gluttony" (hence it starting at Pudding Lane and ending at Pye Corner).

- Check the Museum of London: They have incredible artifacts, including fused pieces of glass and ceramics that show just how hot the fire actually got.

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just take a textbook's word for it. Look up the digital archives of the London Gazette from 1666. It’s fascinating to see how the government "spun" the news as it was happening.

The Great Fire of London 1666 was a disaster, sure. But it was also the moment London stopped being a medieval town and started becoming a global powerhouse. It forced a level of modernization that probably would have taken another century otherwise. It’s a story of incompetence, scapegoating, and incredible resilience.

Next time you’re in a city with brick buildings and wide-ish streets, remember it’s often because someone, somewhere, learned the hard way that wood and narrow alleys don't mix.

Keep an eye on the ground when you walk through the City of London. Sometimes, you can still find the original street levels several feet below the modern pavement. The history is still there, tucked under the concrete, forever changed by four days in September.