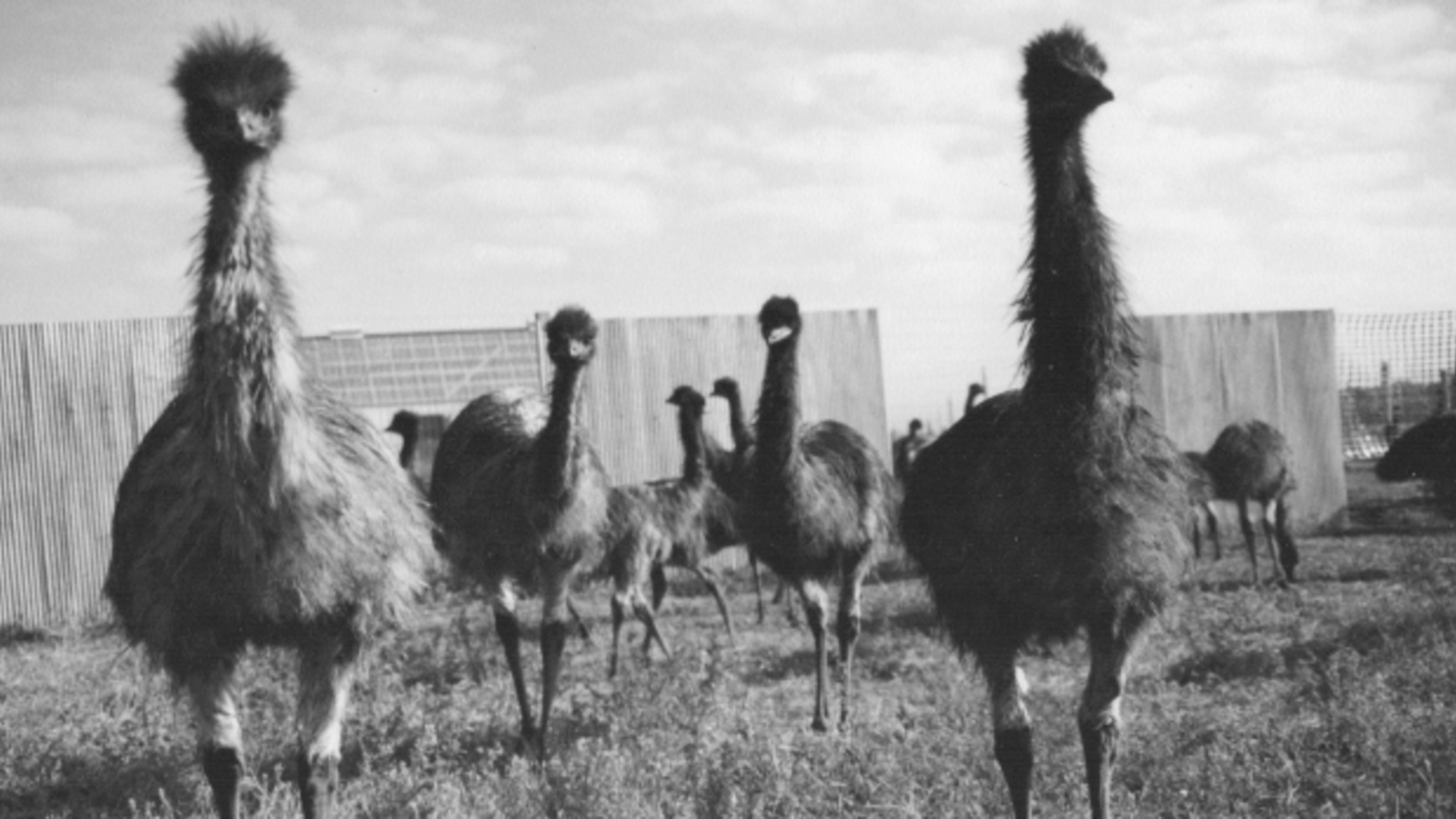

You’ve probably seen the memes. A group of rugged Australian soldiers, armed with Lewis machine guns, somehow managed to lose a military operation against a bunch of flightless birds. It sounds like something pulled straight from a satirical comedy or a fever dream. But the Great Emu War of 1932 was a very real, very weird historical event that actually made international headlines back in the day.

History is weird.

The story usually gets told as a punchline. "The Aussies lost to birds!" While technically true, the reality on the ground in Western Australia was a bit more complicated—and a lot more desperate—than the internet would have you believe. It wasn't just a random skirmish. It was a clash between post-war economic desperation and the brutal reality of Australian ecology.

Why the Australian Government Declared War on Birds

To understand the Great Emu War of 1932, you have to look at the Great Depression. Life in 1932 Australia was rough. World War I veterans had been given land grants in the marginal, arid regions of Western Australia, specifically around Campion and Walgoolan. The government promised them subsidies for wheat. Then the Depression hit. The subsidies never materialized, and wheat prices plummeted.

Then came the emus.

About 20,000 of them.

Every year, after their breeding season, emus migrate from the inland regions to the coast. The veterans-turned-farmers had done something the emus loved: they cleared land and installed irrigation systems. To an emu, a wheat farm isn't just a farm; it’s an all-you-can-eat buffet with a built-in water fountain. These birds didn't just eat the crops. They smashed fences, allowing rabbits—Australia’s other great ecological nemesis—to get in and finish off whatever was left.

The farmers were desperate. They were soldiers. Naturally, they didn't go to the Minister of Agriculture. They went to the Minister of Defence, Sir George Pearce. They asked for machine guns.

The "Military" Campaign Begins

Pearce agreed, but with conditions. The military would provide the guns and the soldiers, while the farmers provided the food, transport, and ammunition costs. It was basically a PR stunt gone wrong. Major G.P.W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery took command. He had two soldiers and two Lewis guns.

🔗 Read more: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

The "war" started in November 1932.

If you’ve ever seen an emu run, you know they aren't easy targets. They can hit speeds of 50 km/h. They’re basically feathered dinosaurs with better reflexes than a professional athlete. On November 2, the troops arrived in Campion. They spotted about 50 emus. The birds did exactly what you’d expect: they scattered. The soldiers tried to herd them into an ambush, but the emus broke into small groups.

The Lewis gun, a reliable weapon in the trenches of the Western Front, was useless here. It was designed for stationary targets or charging infantry. Not for birds that zig-zag through the scrub.

A few days later, Meredith tried a new tactic. He set up an ambush near a local dam where over 1,000 emus were spotted. This was it. The big win. They waited until the birds were in close range. They opened fire. The gun jammed after killing only about a dozen birds. The rest vanished into the dust.

The Guerilla Warfare of the Emu

Ornithologist Dominic Serventy later described the emus as having "guerilla tactics." He wasn't really joking. The birds seemed to develop a command structure. Each mob would have a "lookout"—a large, dark-plumaged male who would stand still and watch for the soldiers while the rest of the flock ate. At the first sign of movement, he’d give a signal, and the flock would bolt in different directions.

Meredith was frustrated. Honestly, who wouldn't be?

In one of the most famous (and slightly ridiculous) moments of the Great Emu War of 1932, the soldiers tried mounting a Lewis gun onto a truck. The idea was to chase the birds down. It failed miserably. The terrain was too rough for the truck to maintain a steady aim, and the driver was too busy trying not to flip the vehicle to worry about where the gun was pointing. One emu actually got tangled in the steering wheel, causing the truck to veer off and crash into a fence.

The birds were winning.

💡 You might also like: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

By the time the first phase was called off on November 8, Meredith’s team had fired 2,500 rounds of ammunition. The official body count? Estimates range from 50 to a couple of hundred birds.

Major Meredith famously remarked:

"If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world... They can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks."

Why Was This a Thing?

You might be wondering why the government didn't just send more men. Or better equipment. The truth is that the Australian public was starting to turn against the "war." Animal rights activists in the UK and Australia were horrified. The media started mocking the whole affair. The House of Representatives debated the cost-effectiveness of the operation.

Federal Labor MP James Lyons famously asked if a medal was to be struck for the "Emu War."

Despite the mockery, Meredith went back out for a second attempt later in November. He was more "successful" this time, claiming nearly 1,000 kills. But in the grand scheme of things, it didn't matter. There were still 19,000 emus roaming the wheat belt. The government eventually withdrew the military, leaving the farmers to deal with the problem themselves.

The Great Emu War of 1932 proved one thing: brute force is a terrible way to manage an ecosystem.

The Aftermath and What We Can Learn

So, how did they actually solve the problem? Not with guns.

📖 Related: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

The government eventually realized that bounties were more effective. Between 1945 and 1960, hundreds of thousands of emus were culled by local hunters who knew the land. However, the real solution was much simpler: better fences. The construction of the Emu Proof Fence (a massive barrier similar to the Dingo Fence) finally gave the farmers the protection they needed.

Today, the Great Emu War is a case study in "wicked problems"—issues that are difficult to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements. It’s also a reminder of the Law of Unintended Consequences. The soldiers arrived expecting a slaughter; they left with a newfound respect for a bird they previously considered a pest.

If you’re looking at this from a modern perspective, there are a few practical takeaways from this bizarre bit of history.

- Technology isn't a silver bullet. The Lewis gun was top-tier tech in 1918, but it was the wrong tool for an ecological problem in 1932. Always match the tool to the environment, not the prestige of the tool itself.

- Respect the "Local Knowledge." The farmers knew the birds were fast, but the military assumed they could just outshoot nature. Bureaucratic solutions often fail because they ignore the nuances of the terrain.

- PR matters. The Australian government thought this would look like they were helping veterans. Instead, it made them look incompetent.

The Great Emu War of 1932 remains one of the most cited examples of human-wildlife conflict gone wrong. It’s a story about the limits of human intervention and the incredible resilience of nature.

If you want to dive deeper into this, I'd suggest looking up the actual parliamentary records from the time—they are surprisingly funny. You can also visit the Western Australian Museum, which holds artifacts and documentation from the era. Most importantly, if you ever find yourself in the Australian Outback, remember: the birds have a perfect record against the military. Keep your distance.

The best way to "win" a war against nature is usually to stop fighting it and start building better fences.

Check out the National Archives of Australia for the original telegraphs sent between the farmers and the Ministry of Defence. It provides a much grittier, less "memey" look at the economic stakes involved. You'll see that while the war was a failure, the struggle of those farmers was a very real part of Australia's national identity during the interwar years.