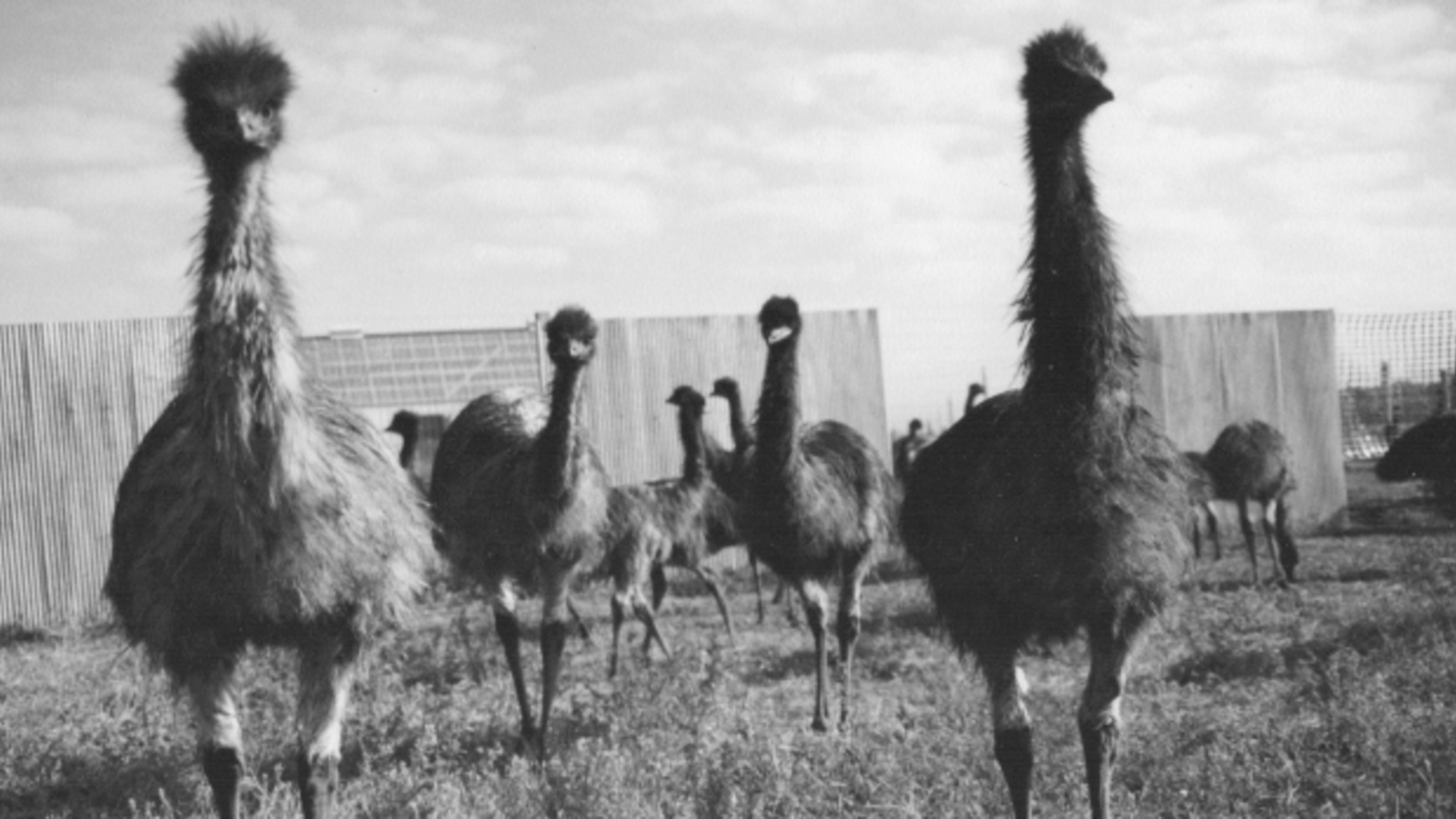

You’ve probably seen the memes. They usually feature a grainy photo of a giant bird and a caption about how the Australian army lost a war to a flightless poultry squad. It sounds like something out of a satirical novel. Honestly, it sounds fake. But the Great Emu War of 1932 was a very real, very weird historical event that actually involved machine guns, thousands of rounds of ammunition, and a lot of embarrassed soldiers.

It wasn't just a prank.

In the early 1930s, Australia was hurting. The Great Depression was in full swing. Farmers in Western Australia—many of whom were World War I veterans—had been encouraged by the government to grow wheat. They did their part. Then the prices dropped, the subsidies didn't show up, and 20,000 emus arrived.

Why the Emu War of 1932 actually started

Emus are nomadic. They usually head to the coast after their breeding season, but these birds found the newly irrigated lands and lush wheat crops of the Campion and Walgoolan districts. It was a paradise for them. They didn't just eat the crops; they smashed fences, leaving huge gaps that allowed rabbits to flood in and finish off whatever the birds missed.

The farmers were desperate.

They didn't go to the Minister of Agriculture. They went to the Minister of Defence, Sir George Pearce. Because these farmers were ex-soldiers, they knew exactly what a Lewis machine gun could do. They figured a few guns would solve the problem in a weekend. Pearce agreed, though historical records suggest he saw it as a good target practice opportunity and a bit of a PR move to show the government was "doing something" for the veterans.

Major G.P.W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery led the charge. He had two soldiers, two Lewis guns, and 10,000 rounds of ammo.

They expected a massacre. They got a lesson in guerrilla warfare.

👉 See also: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

The failure of the Lewis gun and the tactical brilliance of birds

The first engagement happened near Campion in November 1932. The soldiers spotted about 50 emus. The plan was simple: get in range, open fire, and clear the field. But the emus weren't interested in the plan. As soon as the firing started, the birds split into small groups and ran in every direction.

They were fast. Like, 30 miles per hour fast.

A few days later, they tried an ambush at a local dam. Over 1,000 emus approached. This was it. The perfect opportunity. Meredith waited until they were at point-blank range. The guns opened up. After only a dozen or so birds fell, the gun jammed.

The birds just walked away.

Basically, the emus had better leaders than the humans. Observers noted that each pack of emus seemed to have a "leader"—a large, black-plumed male that would stand guard. While the others ate the wheat, the sentry would watch the soldiers. At the first sign of movement, he'd give a signal, and the flock would vanish.

By the fourth day of the Emu War of 1932, army reports were getting bleak. Meredith even tried mounting a machine gun on the back of a truck. It was a disaster. The truck couldn't keep up with the birds on the rough terrain, and the bouncing made it impossible for the gunner to aim. Not a single shot was fired during that high-speed chase.

"If we had a military division with the bullet-resisting capacity of these birds"

Meredith was actually quoted by local press, clearly frustrated, saying that if his men were as tough as the birds, they could face any army in the world. He was impressed by their "invulnerability." He compared them to Zulus because of their ability to withstand hits and keep running.

✨ Don't miss: When is the Next Hurricane Coming 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

The press, meanwhile, was having a field day.

The Sun-Herald and other outlets painted the whole thing as a farce. By November 8, the House of Representatives was debating whether the "war" should continue. The official report claimed only a few hundred birds were killed, though Meredith insisted the number was higher. Either way, the "enemy" was still 20,000 strong and very well-fed on government wheat.

The troops were withdrawn.

But the farmers weren't having it. The emus were still there. The heat was relentless. The wheat was disappearing. After a second wave of complaints, the government sent Meredith back out in mid-November. This time, they were a bit more "successful" in terms of raw numbers. By December 10, Meredith claimed 986 kills with exactly 9,860 rounds.

That is exactly ten bullets per bird.

If you're keeping score, that's a terrible efficiency rate for a professional military unit using automatic weapons against targets that don't shoot back.

Why it matters today: The Emu War of 1932 legacy

We laugh at it now, but the Emu War of 1932 is actually a significant case study in ecology and government overreach. It showed that you can't solve biological problems with purely kinetic solutions. Eventually, the government gave up on the army and went back to a "bounty" system.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

It worked way better.

In 1934 alone, over 57,000 bounties were claimed in a six-month period. The farmers, it turns out, were much better at protecting their own land than a couple of guys with a truck and a jammed machine gun.

Dominic Serventy, the famous Australian ornithologist, described the "war" as an attempt at mass destruction of the birds that ended in "the emu command" maintaining its ground. It’s one of the few times in history a military commander surrendered to a species of bird.

What you can learn from this absurdity

History isn't just dates; it's a series of weird decisions. The Emu War of 1932 teaches us about the law of unintended consequences. The government thought they were helping, but they just ended up creating a global punchline.

If you want to dig deeper into the actual documentation of this event, you should look at the National Archives of Australia. They have the original correspondence between the farmers and the Ministry of Defence. It's much drier than the memes, but the desperation in the farmers' letters is palpable.

You can also look up the work of Dr. Murray Johnson, who has written extensively on the environmental history of Western Australia. He provides the context most people miss—that this wasn't just a funny story, but a failure of land management during a national crisis.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Research the Bounty System: Compare the 1932 military failure to the 1934-1940 bounty success. It's a great lesson in incentive-based policy versus direct intervention.

- Check the Geography: Use Google Earth to look at the Campion and Walgoolan districts. Seeing the vastness of the Australian scrub makes you realize why two guys with one gun had zero chance.

- Read the Official Hansard Records: Look for the Australian Parliamentary debates from November 1932. The snark from the opposing politicians is surprisingly modern.

- Evaluate "Pest" Management: Look into how Australia handles the "Emu problem" today. Spoilers: It involves a lot more fences and a lot fewer machine guns.

The emus are still there. The farmers are still there. The machine guns are in museums. The birds won.