History has a funny way of flattening out the rough edges of reality. When most of us think about the Great Depression of the 1930s, we see a grainy, black-and-white montage of men in dusty flat caps standing in breadlines or Dorothea Lange’s famous "Migrant Mother" looking off into a bleak distance. It feels like a movie. But for the people living through it, it wasn't a historical event; it was a relentless, decade-long grind that fundamentally broke the American psyche.

The money just stopped.

That's the part that is hard to wrap your head around today. In our world of digital currency and instant credit, the idea of the "circulating medium" simply vanishing feels like a ghost story. But by 1933, the United States' Gross Domestic Product had dropped by nearly 30%. Imagine a third of everything—every job, every store, every paycheck—just evaporating into the ether. It wasn't just a "bad market." It was a total systemic collapse that lasted until the massive industrial mobilization of World War II.

Why the 1929 Crash was just the beginning

Most people point to October 29, 1929—Black Tuesday—as the day the Great Depression started.

That’s technically wrong.

While the stock market crash was a massive shock to the system, the economy had actually been cooling off months before the tickers went wild. The crash was the trigger, but the gun was already loaded with high consumer debt, a struggling agricultural sector, and banks that were playing fast and loose with people's life savings.

You have to remember that back then, there was no FDIC. If you heard a rumor that your bank was in trouble, you ran. You didn't walk. You stood in line with hundreds of other panicked neighbors, hoping to get your cash before the vault went dry. If you were 50th in line, maybe you got your money. If you were 500th, you were likely looking at a locked door and a "Closed" sign. Between 1930 and 1933, more than 9,000 banks failed. That's billions of dollars in personal wealth—not corporate wealth, but "I'm saving for a house" wealth—simply deleted from existence.

Economist Milton Friedman famously argued in A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 that the Federal Reserve actually made things worse by shrinking the money supply when they should have been doing the opposite. They tightened the screws when the engine was already seizing up. It was a catastrophic policy error that turned a standard recession into a generational nightmare.

Life on the ground: Hoovervilles and the "New Poor"

The term "Hooverville" wasn't a nickname given by historians. It was a biting, sarcastic jab at President Herbert Hoover, whom many blamed for the perceived inaction of the government.

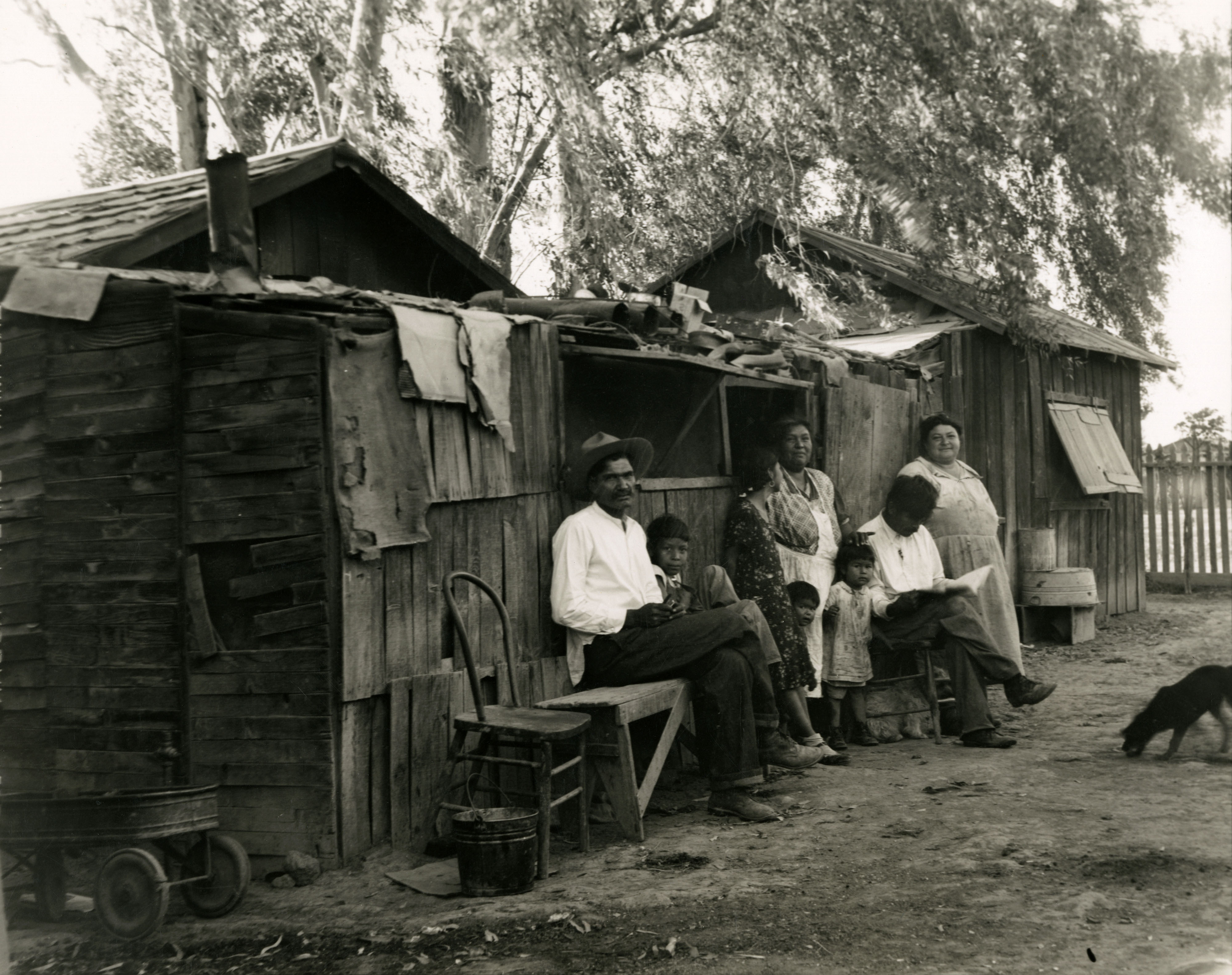

These were shantytowns.

They popped up in city parks and on the outskirts of industrial hubs like St. Louis and New York. People built "houses" out of cardboard, scrap lumber, and old packing crates. They used "Hoover blankets" (old newspapers) to keep warm and "Hoover leather" (cardboard) to patch the holes in their shoes.

It's easy to assume this only happened to the "lower class," but the Great Depression of the 1930s was unique because it decimated the middle class. White-collar workers who had never known a day of hunger were suddenly selling apples on street corners for five cents apiece. There’s a specific kind of shame that comes with that. You’d see men in three-piece suits, brushed but frayed, standing in line for a bowl of watery soup because they couldn't bear to tell their families they had been laid off months ago.

The Dust Bowl: A double-edged sword

As if the financial collapse wasn't enough, the geography of America literally turned on its people.

In the Great Plains, a combination of severe drought and decades of poor farming practices led to the Dust Bowl. The topsoil, dried to a fine powder, was picked up by the wind and carried for hundreds of miles. These "Black Blizzards" were so thick they could suffocate cattle and turn noon into midnight.

If you were a farmer in Oklahoma in 1934, you weren't just broke; you were being buried.

💡 You might also like: Charlotte NC Today News: Why the Queen City is Dominating the Headlines

This led to one of the largest internal migrations in American history. Roughly 2.5 million people left the Plains states. Most headed West toward California, lured by flyers promising picking jobs in the orchards. What they found instead were border guards trying to keep them out and "Hoovervilles" that were even more crowded than the ones they left behind. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath wasn't just fiction; it was a journalistic account of the "Okie" experience.

The New Deal: Radical change or a band-aid?

When Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, he famously told the country that "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself."

It was a great line.

But behind the rhetoric was a frenetic burst of government activity known as the New Deal. FDR was basically throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what would stick. He created the "Alphabet Soup" agencies. The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) put young men to work planting trees and building trails in national parks. The WPA (Works Progress Administration) built bridges, schools, and even hired artists to paint murals in post offices.

A lot of people think the New Deal ended the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Honestly, that’s up for debate.

While these programs provided a massive psychological lift and kept millions from starving, unemployment remained stubbornly high throughout the 1930s. In 1937, there was actually a "recession within the depression" where the economy dipped again. It wasn't until 1941, when the factories started churning out planes and tanks for the war effort, that the unemployment rate finally dropped back to pre-crash levels.

The psychological scars that never healed

If you grew up with grandparents who lived through the thirties, you probably noticed certain habits.

They saved everything.

🔗 Read more: Who Died Today: Remembering the Icons We Lost and Why Their Legacies Matter

Old rubber bands, tin foil, glass jars, bits of string. My grandmother used to wash and reuse plastic wrap. That wasn't just being "thrifty." It was a deep-seated trauma born from a time when nothing was guaranteed. The Great Depression of the 1930s taught an entire generation that the floor could fall out from under them at any second.

It changed the way people viewed the government, too. Before 1929, the federal government was a distant entity that mostly handled the mail and the military. After the 1930s, the expectation changed. People began to believe that the government had a moral and economic responsibility to provide a safety net—Social Security, which was signed into law in 1935, is perhaps the most enduring legacy of that shift.

Misconceptions about the "Good Old Days"

There is a weird nostalgia for the 1930s sometimes—the idea that "people were closer then" or "we knew how to make do."

Sure, community bonds were strong because they had to be. But the reality was grim.

Malnutrition was a serious issue. In some mining towns in West Virginia, 90% of the children were underweight and showing signs of rickets. Marriage rates plummeted because young men couldn't afford to start a family. The birth rate dropped below replacement levels for the first time in American history. It was a decade of "not having"—not having enough food, not having enough work, and not having enough hope.

Surprising facts about the 1930s economy

- The Golden Age of Hollywood: Paradoxically, while the economy was in the trash, the film industry boomed. People would spend their last few cents on a movie ticket just to escape the heat and the misery for two hours. It's why 1939 is considered one of the greatest years in cinema history (Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz).

- Prohibition ended out of necessity: Part of the reason the 21st Amendment was passed in 1933 to legalize alcohol was that the government desperately needed the tax revenue.

- The "Bank Holiday": One of FDR's first moves was to close every single bank in the country for four days. It was a massive gamble to stop the "runs," and it actually worked. When they reopened, people started putting money back in.

Lessons for the modern world

We look at the Great Depression of the 1930s and think it can't happen again because we have safeguards.

We have the FDIC. We have unemployment insurance. We have a much faster flow of information.

But the core lesson of the 1930s is about the fragility of trust. The economy isn't just numbers on a screen; it's a giant, collective agreement that we all believe in the value of our currency and the stability of our institutions. When that trust breaks, it takes more than a decade to glue it back together.

How to use this history today

If you want to understand our current economic landscape, you have to look at the shadows cast by the 1930s. The tension between government intervention and free-market capitalism started here. The debate over the "social safety net" started here.

Actionable Insights:

- Study the 1937 Pivot: Look into why the economy slumped when the government tried to balance the budget too early. It’s a recurring theme in modern fiscal policy.

- Diversify your "Safety": The 1930s proved that even the most "stable" institutions can fail. Modern financial literacy means not keeping all your eggs in one basket—whether that's a single asset class or a single currency.

- Read Primary Sources: Don't just read history books. Go to the Library of Congress digital archives and read the WPA Slave Narratives or the "Life Histories" collected during the 1930s. Hearing the raw, unedited voices of people who lived through it changes your perspective on what "hard times" really look like.

The 1930s didn't just change the economy; they changed the American character. We became more cautious, more community-focused, and significantly more wary of the cycles of boom and bust. Understanding that decade is the only way to make sense of the one we’re living in now.