Chemistry is basically a giant game of counting things you can't actually see. You’re standing in a lab, or maybe sitting at a desk staring at a periodic table, and you’ve got a pile of white powder. You know it weighs 15 grams. But the chemical equation you're looking at doesn't care about grams. It cares about molecules. That’s the disconnect. This is exactly where the grams to moles formula steps in to save your grade—and your experiment.

It’s the bridge between the world we live in (scales and beakers) and the world where reactions actually happen (atoms and ions). Honestly, once you "get" it, the rest of stoichiometry starts to feel less like magic and more like simple currency exchange.

The Math Behind the Magic: Grams to Moles Formula Explained

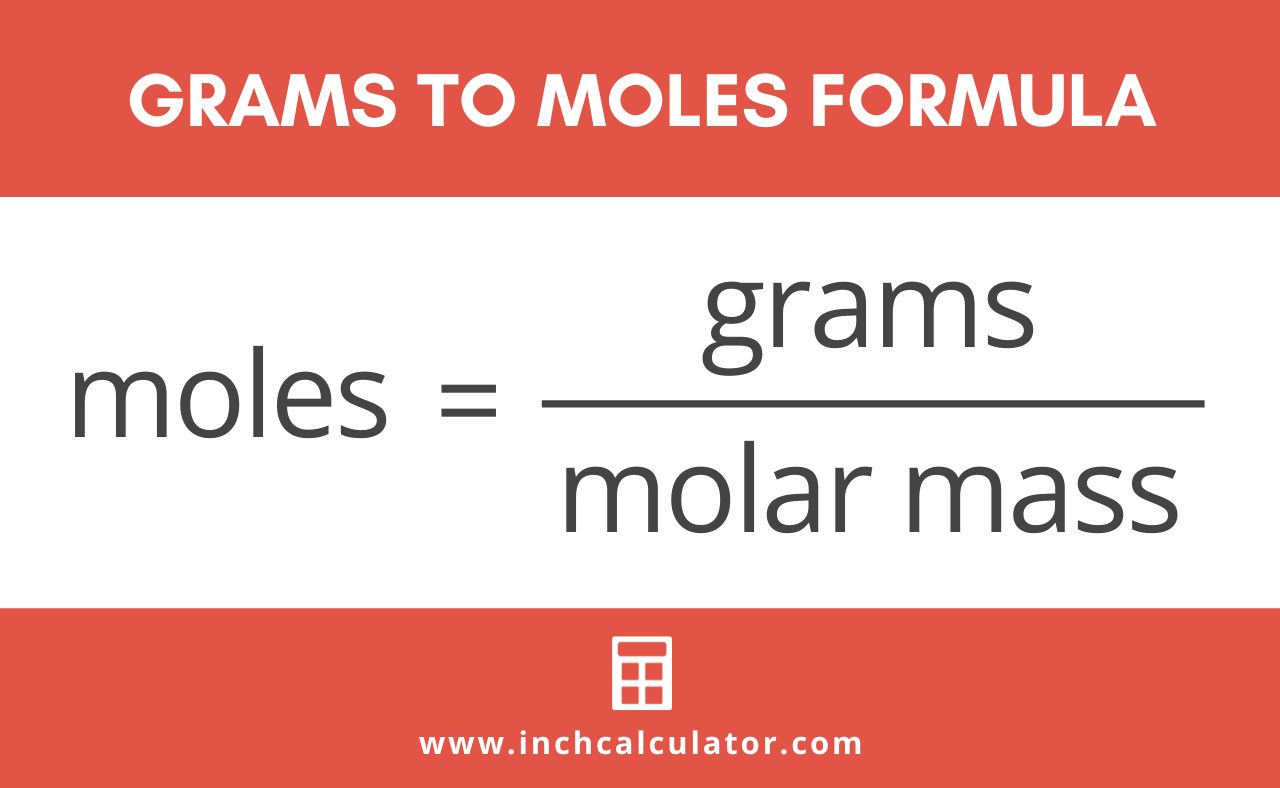

Let’s just get the "scary" math out of the way. It isn't actually scary. The formula is:

$$n = \frac{m}{M}$$

In this setup, $n$ is the number of moles, $m$ is the mass you measured on a scale (in grams), and $M$ is the molar mass of whatever substance you're holding. Think of the molar mass as the "exchange rate." Just like you’d divide your total dollars by the price of a single burger to find out how many burgers you can buy, you divide your total grams by the "weight per mole" to find out how many moles you have.

💡 You might also like: Dokumen pub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Site

Why do we do this? Because atoms are tiny. If you tried to count them individually, you'd be here until the heat death of the universe. A mole is just a way to group $6.022 \times 10^{23}$ particles into one manageable unit. It’s a chemist’s dozen. But unlike a dozen eggs, which always weighs about the same, a "dozen" (mole) of lead weighs a lot more than a "dozen" (mole) of helium.

Finding the Molar Mass Without Losing Your Mind

You can't use the grams to moles formula if you don't know the molar mass. This is where people usually trip up. You have to go to the periodic table. See that decimal number at the bottom of the square for Carbon? 12.011? That’s your molar mass in grams per mole ($g/mol$).

If you’re dealing with a compound like water ($H_2O$), you just add them up. Two hydrogens plus one oxygen.

$1.008 + 1.008 + 15.999 = 18.015\ g/mol$.

Simple.

Why Does This Even Matter?

Imagine you’re a pharmacist or a chemical engineer at a place like BASF or Pfizer. If you’re off by a few "moles" when mixing a batch of medicine, you aren't just making a mess—you're potentially creating something toxic or completely useless.

📖 Related: iPhone 16 Pink Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

In a lab setting, reactions happen based on ratios. If the recipe calls for two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen, it doesn't mean 2 grams and 1 gram. It means 2 moles and 1 mole. If you just tossed in grams without converting, you'd end up with a lot of leftover hydrogen and a very frustrated lab supervisor.

A Real-World Walkthrough

Let’s say you have 50 grams of table salt ($NaCl$). You want to know how many moles that is.

- Identify the mass ($m$): 50 grams.

- Find the molar mass ($M$): Sodium ($Na$) is about $22.99\ g/mol$. Chlorine ($Cl$) is about $35.45\ g/mol$. Add them up to get $58.44\ g/mol$.

- Plug it into the grams to moles formula: $50 / 58.44$.

- Result: You have roughly $0.856$ moles of salt.

It’s a three-step process that most students overcomplicate because they try to memorize the steps instead of understanding the "why." You're just scaling down from the macro world to the micro world.

Common Pitfalls and Annoying Details

The biggest mistake? Units. If your mass is in milligrams or kilograms, the formula breaks. You must convert to grams first. I've seen brilliant students fail exams because they forgot to move a decimal point three places to the left.

👉 See also: The Singularity Is Near: Why Ray Kurzweil’s Predictions Still Mess With Our Heads

Another weird one is the diatomic elements. Remember "BrINClHOF"? Bromine, Iodine, Nitrogen, Chlorine, Hydrogen, Oxygen, and Fluorine. These guys travel in pairs when they're alone. So if a problem asks for the moles in 10 grams of Oxygen gas, you aren't dividing by $16$ (the mass of one Oxygen atom). You're dividing by $32$ ($O_2$). It’s a sneaky trick that catches almost everyone at least once.

The E-E-A-T Perspective: Is It Always This Simple?

If you talk to a theoretical chemist or someone working in high-precision materials science, they might bring up isotopes. The molar mass on the periodic table is actually an average based on how common different versions of an atom are in nature. For 99% of what you’ll ever do, the periodic table average is fine. But in specific fields like nuclear chemistry or carbon dating (shout out to Willard Libby, who won a Nobel for this stuff), those tiny differences in mass actually dictate the whole process.

The grams to moles formula is essentially the foundation of "Stoichiometry," a word that sounds like a disease but just means "measuring elements." It was popularized by Jeremias Benjamin Richter in the late 1700s. He was obsessed with the idea that chemistry followed fixed mathematical laws. He was right.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Conversion

Don't just stare at the formula. Practice it until it becomes muscle memory.

- Grab a periodic table: Keep a physical one or a high-res tab open. Don't guess the masses.

- Check your units twice: If the prompt says $kg$, convert to $g$ before you touch your calculator.

- Write out the units in your fraction: If you write $(50\ g) / (58.44\ g/mol)$, the "grams" cancel out, leaving you with "moles." If the units don't cancel out to leave you with what you want, you set the fraction up wrong.

- Verify the substance: Is it a single atom or a molecule? This changes your molar mass calculation.

Start with simple elements like Gold or Silver. Once you feel confident, move into complex molecules like Glucose ($C_6H_{12}O_6$). The math doesn't get harder; the addition just gets longer.