He wasn't like Negan. Negan had a theater background—metaphorically, anyway—with the leather jacket, the foul-mouthed poetry, and that barbed-wire bat he treated like a wife. But the Governor? Philip Blake was the guy next door who just happened to keep his zombified daughter in a closet and a collection of severed heads in fish tanks. Honestly, that’s what made him so much scarier. When we first meet the Governor in The Walking Dead, he isn't screaming. He’s smiling. He’s offering tea. He’s building a town called Woodbury that looks like a 1950s sitcom set dropped into a nightmare.

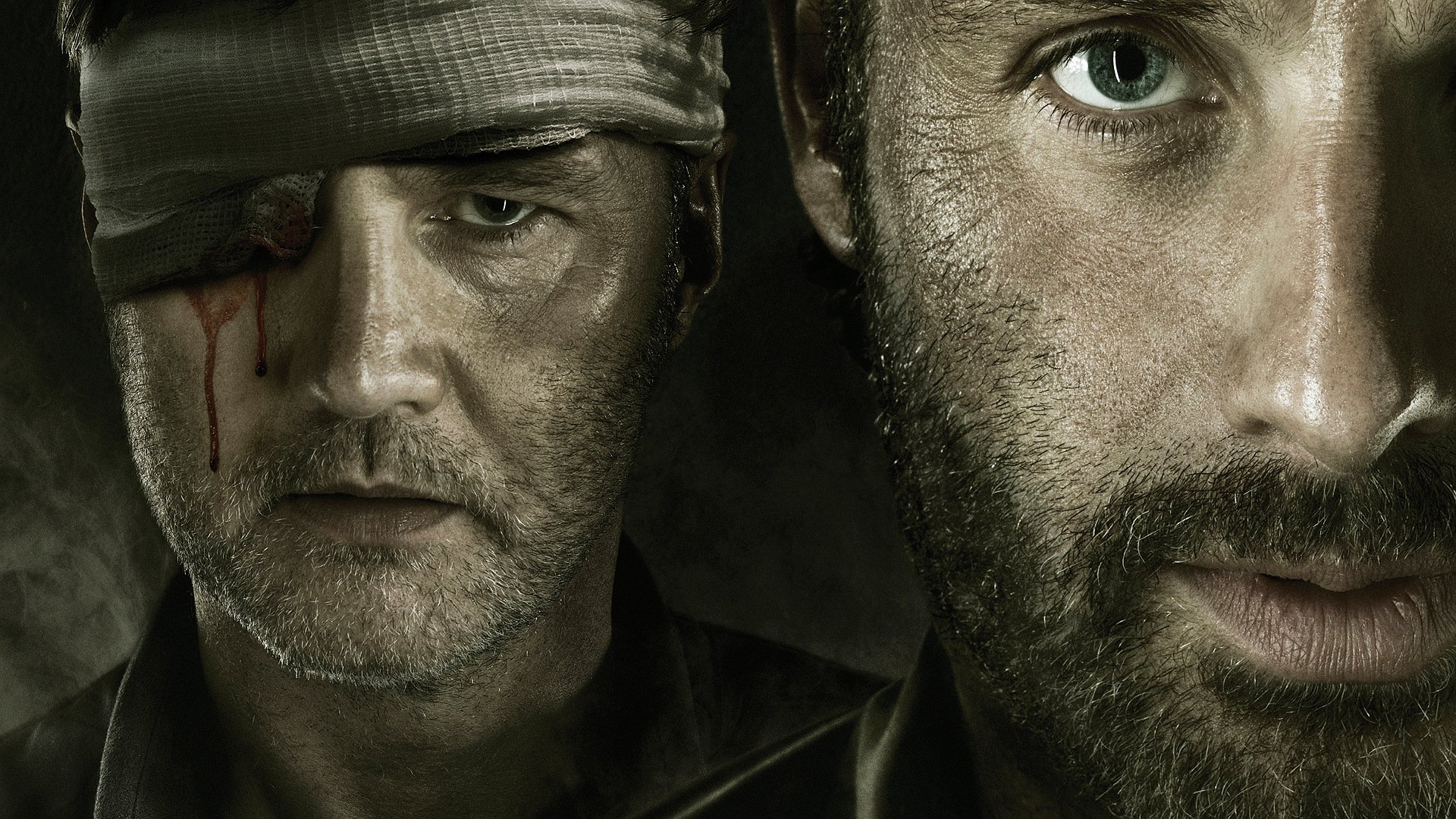

Most people remember the eyepatch. They remember the tank. But if you really look at the trajectory of the show, the Governor was the moment the series stopped being about surviving monsters and started being about surviving people. He was the blueprint.

Woodbury and the Illusion of Safety

Woodbury wasn't just a fortress. It was a psychological trap. David Morrissey played Philip Blake with this simmering, quiet desperation that made you almost believe his lies. You’ve got to remember that at this point in the story, Rick Grimes and his crew were living in a literal prison. They were eating canned beans and sleeping on cold concrete. Then comes Woodbury. There are gardens. There are schools. There are town hall meetings where people feel safe enough to complain about noise ordinances.

The Governor understood something that later villains like Alpha or even Milton from the Commonwealth struggled with: people will forgive a lot of evil if you give them a hot shower and a sense of normalcy. He wasn't a dictator in his own mind. He was a savior. He called himself "The Governor" because it sounded official, boring, and stable. It hid the fact that he was a man who had completely lost his grip on reality the second his daughter, Penny, was bitten.

He kept those heads in the tanks for a specific reason. It wasn't just "creepy villain stuff." He was studying them. He was trying to desensitize himself to the horror of the world so he could rule it. It was a ritual. He’d sit in that dark room, the flickering light of the water reflecting off his face, and just watch. That’s not a man who wants power; that’s a man who has already surrendered to the darkness and is just waiting for everyone else to catch up.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

The Brutality of the Prison War

The conflict between the Prison and Woodbury wasn't just a turf war. It was a clash of philosophies. Rick wanted to build a life; the Governor wanted to possess one. When he chopped off Hershel’s head with Michonne’s katana, it wasn't a tactical move. It was a temper tantrum. He had the prison. He had the leverage. But because Rick offered him a way out—a chance to live together—the Governor called him a liar.

Why?

Because Philip Blake didn't believe in redemption. He knew what he was. He knew he was a murderer and a liar, so he assumed everyone else was too. If he couldn't have the world his way, he’d burn it down. And he did. He literally drove a tank through the fences of the only safe place left in Georgia. He destroyed his own people, gunning them down on the side of the road because they dared to be afraid after a failed raid. That’s the core of the Governor in The Walking Dead. He was a black hole. Everything near him eventually got sucked in and crushed.

The Brian Heriot Arc: A Failed Redemption?

Season 4 gave us something rare. We saw the Governor after he lost everything. He was wandering, beard-grown, looking like a ghost. He took on the name Brian Heriot. He found a new family—the Chamblers. For a second, just a tiny second, you almost thought he’d changed. He bonded with little Meghan. He protected Lilly and Tara.

🔗 Read more: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

But the mask always slips.

He didn't find a new family because he wanted to be a good man. He found them because he couldn't function without someone to "protect" (read: control). As soon as he found another group with resources, he killed their leader, dumped the body in a pond, and took over. He couldn't help himself. Some fans argue that he truly loved Meghan, and maybe he did, but it was a selfish love. It was a love that required him to be the hero, even if it meant leading that family into a war they didn't understand.

What the Comics Did Differently

If you think the TV version of the Governor was bad, the comic book version by Robert Kirkman was a different beast entirely. In the comics, he wasn't a charismatic leader with a tragic backstory. He was a monster from page one. He didn't just take Michonne prisoner; he tortured her in ways the show couldn't even broadcast. He was more of a caricature of evil—a long-haired, mustachioed tyrant who felt like he stepped out of a 1970s grindhouse movie.

The show made him human, which, honestly, made him worse. When David Morrissey’s Governor kills, you see the flicker of pain and then the cold shutter coming down over his eyes. The TV show gave him a soul just so we could watch him throw it away.

💡 You might also like: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

The Legacy of the Eyepatch

The Governor changed the stakes. Before him, the "big bad" was Shane, and that was personal—a brother-vs-brother dynamic. The Governor introduced the concept of the "Big Bad" as a political entity. He paved the way for every villain that followed. Without the Governor, there is no Negan. There is no Alpha. He was the one who taught Rick Grimes that "we're the walking dead."

He also gave us some of the most iconic moments in TV history. The pit of walkers. The gladiator matches in Woodbury. The final showdown in the mud outside the prison where Michonne finally put her sword through his chest. It was a messy, ugly, desperate end for a man who tried to dress up the apocalypse in a suit and tie.

How to Analyze the Governor's Impact

If you’re revisiting the series or writing about it, look at these specific elements:

- The Power Vacuum: Notice how Woodbury collapses the moment the Governor loses his focus on the "picket fence" lie.

- The Symbolism of Penny: She represents his refusal to accept the new world. By keeping her "alive," he stays tethered to a world that died, preventing him from ever truly leading.

- The Mirror Effect: Compare the Governor’s "Brian Heriot" phase to Rick’s "Farmer Rick" phase. Both tried to quit the violence. Only one of them was doing it for the right reasons.

To really understand the Governor in The Walking Dead, you have to look past the villainy and see the grief. He was a man who couldn't handle the loss of the old world, so he tried to build a small, violent version of it where he was the only one who got to make the rules. He wasn't a king. He was just a grieving father who decided that if his world ended, everyone else's should too.

Next time you watch the "Too Far Gone" episode, pay attention to his face right before he swings the sword. It isn't anger. It’s a total, hollow emptiness. That’s the real Governor.

If you are looking to understand the character further, compare his leadership style to the "Social Contract" theory. He provided security at the cost of liberty, a classic authoritarian trade-off that eventually fails when the leader’s personal grievances outweigh the needs of the collective. Reviewing Season 3, Episode 3 ("Walk with Me") alongside Season 4, Episode 8 ("Too Far Gone") provides the clearest picture of his rise and inevitable self-destruction.