Google Glass didn't just fail; it became a punchline. But honestly, if you actually wore one of those Explorer Edition units back in 2013, you’d know the Google Glass user interface was actually a masterclass in constraint. It had to be. You were basically trying to navigate a computer with a tiny piece of glass hovering over your right eye, and that meant the "desktop" as we knew it was dead on arrival.

It was weird. It was glitchy. But it was also strangely intuitive once you stopped trying to treat it like a floating smartphone.

The whole thing relied on a "timeline" metaphor. Think about your Twitter feed or a Facebook wall, but stretched out horizontally. You’d swipe your finger along the side of the frame—the actual hardware was the mouse—to scroll through "cards." Past events, like photos you took or emails you received, lived to the right of the home screen. Future stuff, like upcoming calendar appointments or Google Now cards (remember those?), lived to the left.

The "Timeline" and the Death of the App Icon

Most people expected a grid of icons. They wanted a tiny Android phone in their eye. Google realized that would be a total disaster for focus. Instead, the Google Glass user interface forced everything into a single, linear flow.

If you took a photo, it didn't just go into a gallery folder. It landed on your timeline. You could tap the touchpad to "peel" back layers of that card. One tap brought up a menu: Share, Delete, or Edit. It was incredibly shallow navigation. You rarely had to go more than two or three taps deep to get anything done, which was a necessity because holding your hand up to your temple for more than thirty seconds makes you look like you're having a very localized mid-life crisis.

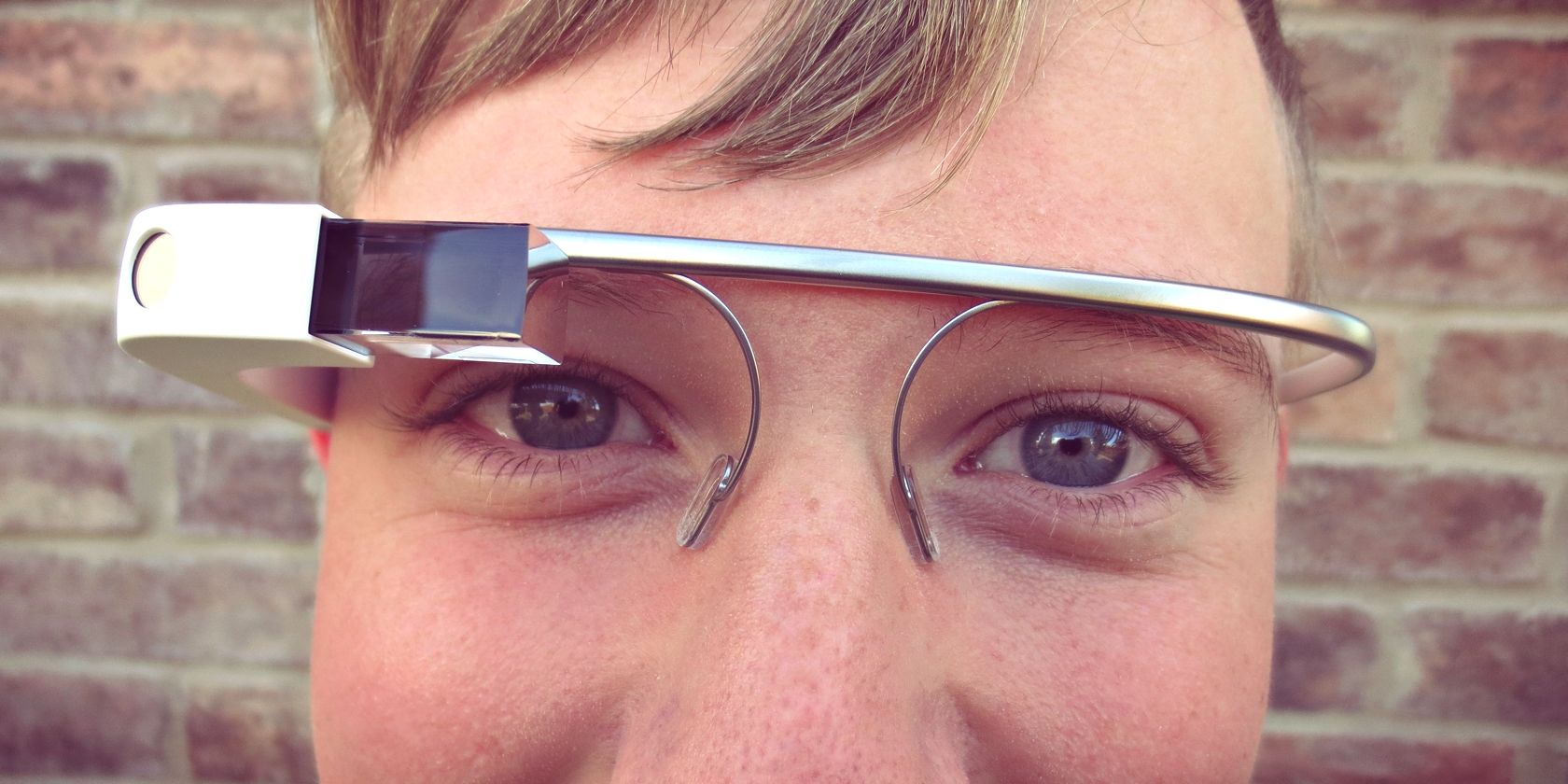

The display itself, a 640 x 360 pixel prism, didn't actually sit in front of your eye. It sat just above your line of sight. To see the UI, you had to look up. This was intentional. Google’s design team, led by folks like Isabelle Olsson, wanted "micro-interactions." They didn't want you staring at a screen; they wanted you to glance, get the info, and get back to the real world.

💡 You might also like: Why -60 Celsius to Fahrenheit is Way Colder Than You Actually Think

Voice Commands: "OK Glass" and the Social Friction

We take "Hey Siri" for granted now, but the Google Glass user interface was the first time voice was the primary input for a mainstream wearable. It was the "OK Glass" era.

You’d tilt your head up—an action the device detected via accelerometer—and say the magic words. From there, a list of verbs would appear. "Take a picture." "Record a video." "Send a message to Mom." It worked surprisingly well in quiet rooms, but the second you stepped into a crowded Starbucks, the UI became a nightmare. You’d find yourself screaming at your glasses while everyone else backed away slowly.

The software, originally called "XE" (Exploratory Edition), went through dozens of updates. Early on, the UI was incredibly bare-bones. By XE12, they added things like "wink to take a photo," which was both technically impressive and socially terrifying. People hated it. It made the interface feel invasive.

Why the Prism Design Actually Made Sense

There’s a lot of talk about "field of view" in AR today. High-end headsets like the Magic Leap or the HoloLens try to cover your whole eye. Glass didn't. The UI stayed in that tiny, translucent box.

- Transparency: Because the cards were semi-transparent, you didn't lose your peripheral vision.

- Contextual Awareness: The UI would pull in Google Now data. If you were at an airport, the boarding pass card would just... appear.

- Low Latency: Because the UI was so simple—mostly text and flat colors—it stayed snappy even on the mediocre Texas Instruments OMAP 4430 processor it was running.

Honestly, the Google Glass user interface was ahead of its time in how it handled notifications. It didn't buzz your wrist like an Apple Watch. It chirped. Using bone conduction, the sound vibrated through your skull. It was a private UI experience that nobody else could see or hear, which added to the "Glasshole" mystique.

The Enterprise Pivot: Glass Enterprise Edition 2

While the consumer version died a loud, public death, the Google Glass user interface found a second life in factories. DHL and Boeing started using it. They didn't need a timeline of their Twitter mentions; they needed schematics.

The UI for the Enterprise Edition 2 is much more "assisted reality" than "augmented reality." It’s basically a heads-up display (HUD). Workers see a checklist. They see a "see-what-I-see" video call from a supervisor. It's boring. It's functional. And it's exactly where the UI should have stayed from the beginning.

There's no fancy scrolling. It's just: Here is the bolt you need to tighten. Tap. Next step. It turns out that when you remove the "lifestyle" aspect of the UI, the hardware actually becomes useful.

What Designers Can Learn from the Glass UI Failures

If you’re building anything in AR or wearable tech today, you have to look at the Google Glass user interface as a cautionary tale of "social signaling." The UI wasn't just on the screen; it was on your face.

The biggest mistake was the "head-tilt" wake gesture. While it made sense for the software to save battery, it made the user look erratic to outsiders. Modern UIs like the Apple Vision Pro use eye-tracking and subtle hand gestures for a reason. They learned that a UI that requires "loud" body language is a UI that people will eventually reject.

Also, the "flat" design of the Glass cards was a bit too minimalist. Sometimes you’d be scrolling and have no idea where you were in the timeline. There was no "home" button. You had to swipe down—a universal "back" or "exit" gesture—multiple times to get back to the clock. It was frustrating.

The Legacy of the Card System

Look at your phone's lock screen right now. Those rectangular notifications with rounded corners? Those are the descendants of the Google Glass user interface. Google took the "Card" concept from Glass and baked it into Android (and eventually the rest of the web).

The idea that information should be "snackable" and modular came directly from the constraints of that 2013 prism. We didn't get the glasses, but we got the design language.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights for AR Fans

If you're still fascinated by the way we interact with head-mounted displays, don't just look at the shiny new stuff. There's a lot to be gained from the "minimalist" mistakes of the past.

- Prioritize Glanceability: If a user has to look at a wearable UI for more than 5 seconds, the UI has failed. The Google Glass user interface excelled at this—it was designed for 2-second check-ins.

- Audio is Part of the UI: Glass proved that visual UI isn't enough. Bone conduction and voice feedback are critical when the screen real estate is tiny.

- Control the Privacy Narrative: The UI should always indicate when it’s "active" to the people around you. One reason Glass failed was that bystanders didn't know if the user was looking at a map or recording them.

- Avoid "Floating Smartphone" Syndrome: Don't try to port 2D apps to a 3D space. Glass tried to be a timeline; modern AR tries to be a world. Both need to respect that the user's primary "interface" is still the physical world they're walking through.

The Google Glass user interface wasn't perfect, but it was a brave attempt to solve a problem we're still struggling with: how to stay connected without being buried in a screen. We're moving toward a world of "Ambient Computing," and whether we like it or not, the DNA of those awkward, blocky cards is going to be all over the next generation of smart glasses.