You’ve probably seen it. A grainy, sepia-toned list titled "The Good Wife's Guide" or references to the Good Wife Awards floating around Facebook and Pinterest. It’s got all those cringey rules from the 1950s—have dinner ready, touch up your makeup, and for heaven's sake, don't complain if your husband comes home late. It feels like a time capsule of a much more rigid era. But honestly? Most of what people share about these "awards" or the "guide" is a total fabrication, or at the very least, a massive historical misunderstanding.

History is messy.

Where the Good Wife Awards Myth Actually Started

If you try to find a physical trophy or a verified list of winners for something called the Good Wife Awards from the mid-century, you’re going to be looking for a long time. It doesn't really exist in the way the internet wants it to. Most of the viral "evidence" stems from a supposed article in Housekeeping Monthly dated May 13, 1955.

Here is the kicker: Housekeeping Monthly wasn't even a real magazine back then.

Researchers and librarians at places like the Advertising Archives have debunked the 1955 "Guide" repeatedly. It’s a piece of digital folklore. While the 1950s were definitely a time of intense domestic pressure for women, this specific list of rules—like "be a little gay and a little more interesting for him"—is widely considered a modern hoax that first surfaced around 1998. It was likely an email forward that just never died. People love to be outraged by the past, and this was the perfect bait.

Real 1950s Domesticity Was More Complicated

We shouldn't pretend the era was a feminist utopia. It wasn't. But the Good Wife Awards narrative oversimplifies what life was actually like. If you look at actual publications from the time, like Good Housekeeping or Ladies' Home Journal, the advice was often more practical and less... subservient... than the viral memes suggest.

Sure, there were advertisements showing women looking ecstatic about a new vacuum cleaner. However, there was also a growing undercurrent of frustration. This is exactly what Betty Friedan eventually tapped into with The Feminine Mystique in 1963. She called it "the problem that has no name." Women were winning the "awards" of social approval by having the perfect home, but they were often miserable.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Real life isn't a meme.

The TV Show Connection

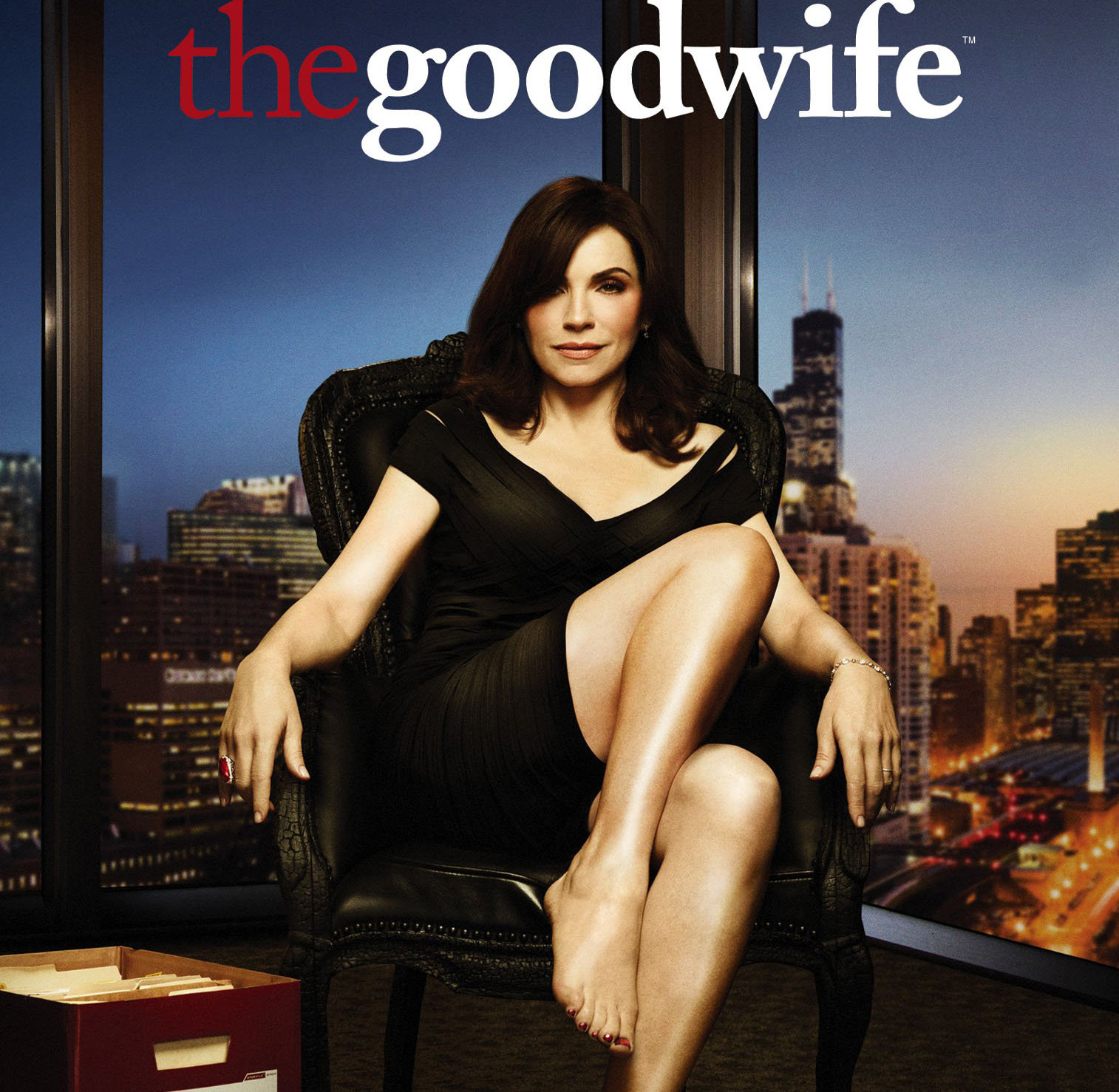

A huge reason the search volume for Good Wife Awards spiked in the last decade has nothing to do with 1955. It’s because of the CBS legal drama The Good Wife, starring Julianna Margulies. In the show, the protagonist, Alicia Florrick, has to navigate the fallout of her husband’s very public sex and corruption scandal.

The title itself is a sarcastic jab.

The show explores the "Stand by Your Man" trope. It asks what it actually means to be a "good wife" when your partner has utterly humiliated you. Throughout the series, Alicia wins various professional accolades and "Woman of the Year" type honors, which fans sometimes conflate with the idea of a Good Wife Award. In the show's universe, these awards are often political tools, used to craft an image rather than reward actual virtue.

Why We Keep Sharing the Hoax

Why does that fake 1955 list keep coming back?

Basically, it’s a "shiver" factor. We look at it and feel superior. We think, "Wow, look how far we've come." It's a way to validate modern progress. But when we focus on fake history like the Good Wife Awards, we miss the real nuances of the past. For instance, in the 1950s, many women were actually entering the workforce in record numbers following WWII, even if the media was trying to push them back into the kitchen.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

The myth ignores the reality of working-class women and women of color who never had the luxury of "preparing the children" and "minimizing all noise" for a returning husband. They were too busy working their own shifts.

Spotting the Fake History

If you see a post about the Good Wife Awards or the 1955 Guide, look for these red flags:

- The Date: It’s almost always May 13, 1955.

- The Source: Housekeeping Monthly (which didn't exist).

- The Tone: It sounds slightly too much like a parody of the 50s.

- Image Quality: It's usually a low-res JPEG that looks like it's been screenshotted a thousand times.

Actual Advice from the Era

If you want to know what experts actually told women back then, look at the work of Dr. Marynia Farnham or the various marriage manuals of the 1940s and 50s. They were often focused on "psychological adjustment." The goal was stability. After the chaos of the Great Depression and World War II, society was obsessed with the idea of the "nuclear family" as a bulwark against communism and social collapse.

It wasn't about a trophy or a Good Wife Award. It was about performing a role to keep the world from feeling like it was falling apart again.

Honestly, the pressure was immense. It wasn't just about dinner; it was about the survival of the American Way of Life. That’s a lot heavier than a list of rules about hair ribbons.

The Evolution of the "Good Wife" Label

Today, the term has been reclaimed and deconstructed. From the "TradWife" movement on TikTok—which some see as a return to those 1950s ideals—to the high-powered career women who still feel the "second shift" at home, the ghost of the Good Wife Awards still haunts us.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

The "TradWife" creators often reference these old-school aesthetics. They post videos of baking bread from scratch in floral dresses. While they might not call it a "Good Wife Award," the social media validation (likes, shares, followers) acts as a modern equivalent. It's the same performance, just on a different platform.

But again, it’s mostly a performance. It's curated.

How to Handle Historical Misinformation

When researching things like the Good Wife Awards, it's better to go to primary sources. Check digital archives of real newspapers from the 1950s. Use sites like Chronicling America (Library of Congress) or the HathiTrust Digital Library.

You’ll find that while the 1950s were conservative, they weren't a monolith. People were arguing about gender roles just as much then as they are now. They just didn't have Twitter to do it on.

Actionable Steps for Evaluating Retro Content

- Reverse Image Search: If you see a "vintage" list, pop it into Google Lens. See if a fact-checking site like Snopes has already tackled it.

- Check the Publication: Google the name of the magazine. If the only mentions of it are in the viral post itself, it's fake.

- Look for Anachronisms: Phrases like "inner peace" or "quality time" often didn't enter the common domestic vocabulary until much later.

- Context Matters: Distinguish between a satirical piece (which the original "Guide" may have been intended as) and an actual instructional manual.

The Good Wife Awards may be a myth, but the pressure on women to perform domestic perfection is very real. Understanding the difference between a fake internet meme and actual history helps us see that clearly.

Next Steps for Deep Research

To get a true sense of 1950s domestic expectations, bypass the memes and look into the McCall's Magazine archives from 1954, specifically the "Togetherness" campaign. This was a real marketing push that defined the era's family dynamics far more than any fake award list. Additionally, reading "The Way We Never Were" by Stephanie Coontz provides a definitive, evidence-based breakdown of why our collective memory of the 1950s—including the "Good Wife" tropes—is largely a historical fiction constructed decades later. Finally, examine the 1944 Education Act (UK) or the GI Bill (US) to see how government policy, rather than "housewife guides," actually shaped the domestic lives of women during the post-war period.