Kendrick Lamar didn't just drop a classic in 2012. He dropped a photo album. If you look at the good kid, m.A.A.d city album cover, you aren't seeing a high-budget studio session or some glossy, airbrushed portrait of a rising star. You’re looking at a kitchen table in Compton. It’s grainy. It's a bit yellowish. There’s a baby Kendrick sitting there, looking completely oblivious to the fact that his uncles are throwing up gang signs right next to his head.

It’s raw.

That’s the whole point. This isn't just marketing; it's a thesis statement for one of the greatest concept albums ever made. Honestly, if Kendrick had gone with a standard "rapper posing in front of a car" shot, the music would still be great, but the story wouldn't feel as heavy. That Polaroid tells you everything you need to know about the conflict between innocence and the environment before you even hear a single beat from "Sherane a.k.a Master Splinter’s Daughter."

What’s actually happening in that photo?

People see the good kid, m.A.A.d city album cover and usually focus on the "m.A.A.d" part—the gang culture. But look closer at the table. You see a 40-ounce bottle of malt liquor sitting right there next to a baby bottle. That’s not a mistake. It’s the visual representation of the album’s title. Kendrick is the "good kid" in the middle of a "m.A.A.d city."

The men in the photo are Kendrick’s family members. Specifically, it features his two uncles and his grandfather. One of the uncles has his face censored out with a black bar. In various interviews, Kendrick has mentioned that this wasn't just a stylistic choice to look "edgy." It was about privacy and the reality of the streets. Not everyone in that photo wanted to be a public figure, or perhaps more accurately, not everyone in that photo was in a position to be one.

The image was taken by Kendrick’s uncle. It captures a moment of domestic life that is simultaneously mundane and dangerous. The eyes of the men are censored, which forces you to look at the child. Kendrick is the only one we can truly "see." He is the witness.

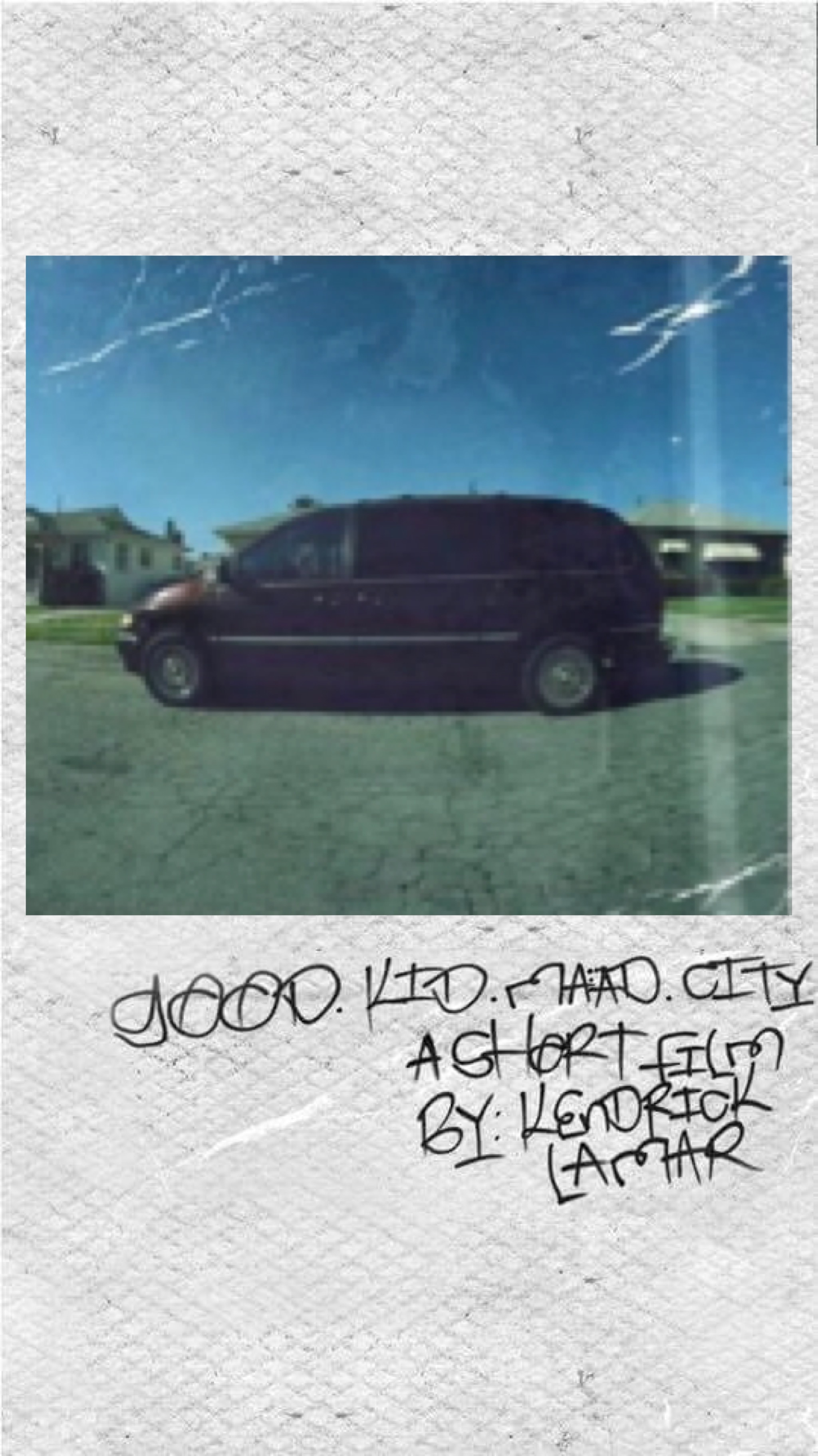

The "Deluxe" alternative and the van

If you didn't buy the physical CD or if you primarily use streaming services, you might be more familiar with the other good kid, m.A.A.d city album cover—the one with the silver Chrysler Town & Country van.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

That van is a character.

In the narrative of the album, that van is where the "m.A.A.d city" happens. It’s the vehicle for the "joyrides" that turn into something much darker. Kendrick has called it the "Death Van." Seeing it parked against a plain white background on the deluxe cover makes it look like an artifact in a museum. It's a piece of evidence.

While the standard Polaroid cover represents the "Good Kid" (the internal, the family, the roots), the van cover represents the "m.A.A.d city" (the external, the peer pressure, the streets). Most fans actually prefer the Polaroid because it feels more personal, but the van is arguably more iconic to the literal plot of the songs.

Why the Polaroid aesthetic changed hip-hop visuals

Before 2012, rap covers were getting pretty polished. We were in the era of Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy paintings and Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter III baby photos, which were professionally shot to look "vintage."

Kendrick went the other way. He used an actual family photo.

This sparked a massive trend in the 2010s of "lo-fi" and "archival" album art. Suddenly, everyone wanted their cover to look like it was pulled out of a shoebox in a closet. But with Kendrick, it wasn't a trend. It was necessary. He was telling a nonlinear story about his teenage years. You can't tell a story about memory using 4K high-definition photography. It has to be blurry. It has to be a little bit faded.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The hidden details you probably missed

- The 40oz vs. The Baby Bottle: As mentioned, this is the most direct symbolism on the table. It represents the immediate transition from childhood to the vices of the neighborhood.

- The Gang Signs: The uncle on the right is throwing up a sign. It anchors the "good kid" in a specific reality. Kendrick isn't hovering above the madness; he's sitting right in the lap of it.

- The Kitchen Setting: Most of the album's dialogue skits take place in kitchens or cars. The cover sets the stage for those "skits" (which are actually cinematic interludes).

- The Font: The handwriting-style font used for the title looks like something a kid would scrawl in a notebook. It reinforces the "diary" feel of the project.

The "Truth" behind the black bars

A lot of people think the black bars over the eyes are just a tribute to 1990s documentary style. While that's partly true, Kendrick told Fuse back in the day that the photo was a "true story." He wanted to show the people who influenced his life without exposing them to the "vultures" of the industry.

There’s a level of protection there.

It also plays into the theme of identity. Throughout the album, Kendrick is trying to figure out who he is. Is he the kid his mom wants him to be, or is he the kid his friends want him to be? By blurring the faces of the adults, the cover suggests that their identities were already fixed by their environment, but Kendrick’s—the one face we see—was still undecided.

How it compares to To Pimp a Butterfly

If you look at his follow-up, To Pimp a Butterfly, the cover is a massive group photo in front of the White House. It’s a statement about society, politics, and the world.

But the good kid, m.A.A.d city album cover is the opposite. It’s tiny. It’s private.

It’s the "before" picture. You can't understand the man standing on the lawn of the White House in 2015 if you don't understand the toddler sitting at that kitchen table in the late 80s.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

The lasting legacy of the artwork

Whenever a classic album anniversary rolls around, we talk about the tracks. We talk about "Money Trees" or "Sing About Me, I'm Dying of Thirst." But the visual of that Polaroid is what pops into your head the second the beat drops.

It’s one of those rare cases where the artwork and the audio are perfectly symmetrical. The music is dense, layered, and a bit hazy. The cover is exactly the same. It’s a masterpiece of art direction because it doesn't feel like "art direction" at all. It feels like a memory.

If you’re a collector, the vinyl version of this album is one of the few where the "Standard" and "Deluxe" covers are often swapped or offered as gatefolds. Seeing the Polaroid blown up to 12x12 inches reveals even more grain and more detail in the background—the wood paneling on the walls, the specific brand of the beverage on the table. It’s a time capsule.

How to appreciate the cover even more

To truly get what Kendrick was doing, you should try these three things the next time you listen:

- Sync the Skits: Listen to the "Momma" and "Poppa" skits while looking at the Polaroid. It grounds the voices in a physical space.

- Contrast the Colors: Compare the warm, orange hues of the Polaroid cover with the cold, sterile grey of the Van cover. It shows the two sides of Kendrick's Compton—the warmth of home vs. the coldness of the streets.

- Read the Credits: Look up the photography credits. Notice how much of Kendrick’s creative team, like Dave Free and the TDE crew, prioritize these "home movie" aesthetics across his entire videography. It all started here.

The good kid, m.A.A.d city album cover remains a benchmark for how to use personal history to sell a global narrative. It’s not just a photo of a family; it’s a photo of a moment before the world changed for a kid from Compton.