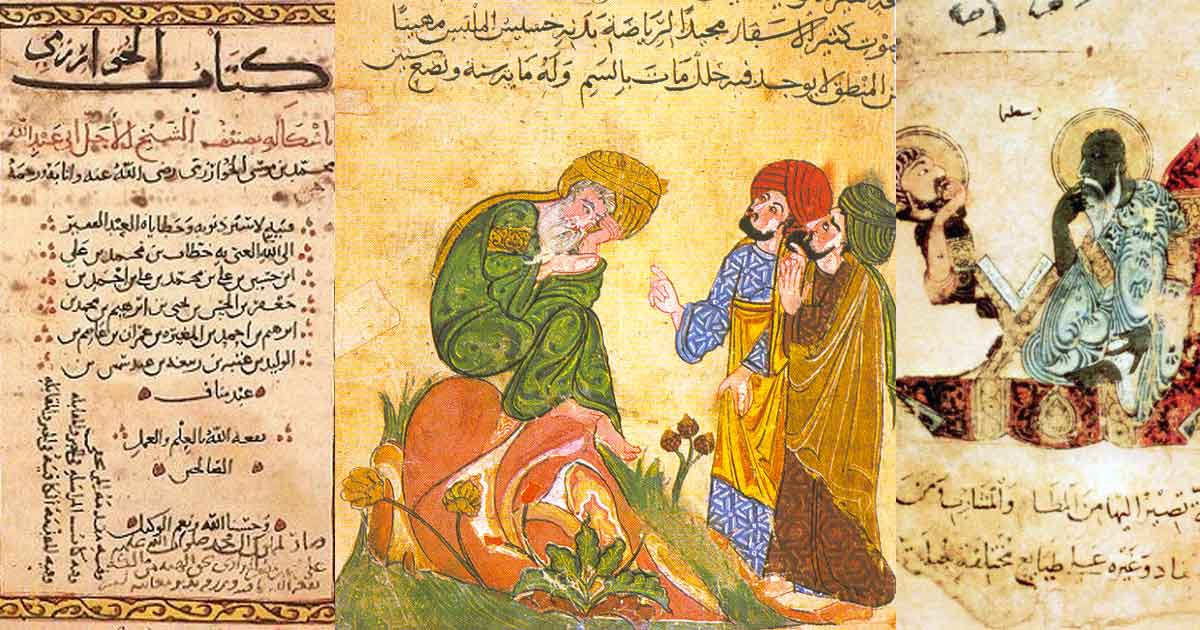

If you walked into a hospital in 10th-century Baghdad, you wouldn’t find a place of superstition or primitive "bloodletting" as the primary cure. Instead, you'd likely encounter a sophisticated medical center with specialized wards, a pharmacy, and a teaching wing. Doctors there were already performing cataract surgeries and documenting the contagious nature of tuberculosis. This was the Golden Age of Islamic civilization, a period roughly spanning from the 8th to the 13th century that basically laid the groundwork for the modern world, though we rarely give it the credit it deserves.

History is weirdly selective. We often hear about the Greeks and then a massive gap until the Renaissance, as if humanity just took a collective nap for a thousand years. It didn't. While Europe was largely struggling through the Early Middle Ages, a massive intellectual explosion was happening across the Middle East, North Africa, and Al-Andalus (Spain).

The House of Wisdom wasn't just a library

Think of the Bayt al-Hikma, or the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, as the Silicon Valley of the 9th century. It wasn't just a quiet room with dusty scrolls. It was a massive research hub funded by the Abbasid Caliphs, specifically Al-Ma'mun. He was obsessed with knowledge. Like, "pay an author the weight of their book in gold" obsessed.

This sparked the Translation Movement. Scholars didn't just translate Greek, Persian, and Indian texts into Arabic; they interrogated them. They found mistakes. They added their own experiments.

One guy you’ve gotta know is Al-Khwarizmi. Honestly, your life would be unrecognizable without him. He was a Persian mathematician at the House of Wisdom who wrote Kitab al-Jabr. Does that sound familiar? It’s where we get the word "Algebra." He didn't just invent a math class people hate in high school; he gave us the concept of algorithms. No Al-Khwarizmi, no Google. No Instagram. No digital world. It’s that simple.

He also popularized the use of Hindu-Arabic numerals—the 0, 1, 2, 3 we use today. Before that, Europe was stuck with Roman numerals. Try doing long division with Roman numerals (MCCLIV divided by IV?). It’s a nightmare. The introduction of the zero was a total game-changer for mathematics and trade.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Medicine and the "Canon" that ruled Europe

When we talk about the Golden Age of Islamic achievement, we have to talk about Ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna. He was a bit of a polymath—most of these guys were. By the age of 18, he was already a famous physician.

His most famous work, The Canon of Medicine, became the standard medical textbook in Europe for over six hundred years. Six centuries! He was the first to realize that some diseases were spread through water and soil. He also detailed the use of anesthesia and recognized that emotional health affects physical health—a concept we’re only now "rediscovering" in modern wellness circles.

Then there’s Al-Zahrawi. He lived in Cordoba and is basically the father of modern surgery. He wrote an encyclopedia of medicine called Al-Tasrif. In it, he described over 200 surgical instruments, many of which he designed himself. Forceps? He used them. Catgut for internal stitches? That was him too. He realized that if you used animal intestines for sutures, the body would eventually dissolve them, preventing the need for a second surgery to remove the threads. Genius.

Optics, Cameras, and How We See the World

For a long time, people—including the great Ptolemy—thought our eyes emitted rays of light to "touch" objects so we could see them. It was called emission theory.

Ibn al-Haytham, an 11th-century physicist, thought that was nonsense. While he was under house arrest in Cairo (long story involving a failed dam project on the Nile), he spent his time experimenting with light. He proved that light reflects off objects and enters the eye.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

He created the camera obscura—a dark room with a tiny pinhole that projected an upside-down image of the outside world onto a wall. This is literally how your smartphone camera works today. His Book of Optics shifted the entire field of physics from abstract philosophy to experimental science. He’s arguably the person who actually invented the scientific method as we know it: hypothesize, test, observe, repeat.

The Misconception of "Religion vs. Science"

People often ask: "Wait, wasn't this a religious society? How did science flourish?"

In the Golden Age of Islamic thought, there wasn't a hard line between the two. In fact, many scientific pursuits were driven by religious needs.

- You need to know the exact direction of Mecca from anywhere in the world? You better get really good at spherical trigonometry.

- You need to know when to pray based on the sun's position? You need advanced astronomy.

- You want to distribute inheritance according to complex laws? You need algebra.

The Quran encouraged the study of the natural world as a way to understand the Creator. This wasn't science despite religion; it was science because of it.

The decline of this era is debated. Some point to the Mongol Siege of Baghdad in 1258, where the Tigris River supposedly ran black with the ink of books thrown into it. Others point to a shift in philosophical priorities toward more traditionalist theology. The truth is probably a mix of economic shifts, political instability, and the changing of trade routes.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Practical Insights: Why This History Matters Now

Studying the Golden Age of Islamic history isn't just a trip down memory lane. It offers some pretty heavy lessons for today's world.

Knowledge is a global baton race.

The Greeks passed the baton to the Muslims, who refined it and passed it to the Europeans, who eventually sparked the Enlightenment. No single culture "owns" science. It’s a collective human effort. Recognizing that Al-Haytham influenced Newton or that Ibn al-Shatir’s planetary models look suspiciously like Copernicus’s work doesn't take away from the latter; it just gives us a more honest picture of how discovery works.

Diversity drives innovation.

The House of Wisdom wasn't just for Muslims. It was a hub for Christians, Jews, Sabians, and Zoroastrians. They worked together because the pursuit of truth was seen as a universal value. When societies open up to different perspectives, they tend to explode with creativity.

The value of the "Polymath" mindset.

In the modern world, we’re pushed to specialize early. We become "data analysts" or "radiologists." But the giants of the Islamic Golden Age were poets, philosophers, astronomers, and physicians all at once. Sometimes, the best solution to a math problem comes from looking at a star or reading a poem.

How to apply these lessons:

- Read the primary sources. Instead of just reading "about" them, check out translations of Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah. He basically invented sociology and economics centuries before Adam Smith.

- Audit your "History Bias." When you look at a modern invention, dig deeper. Ask who laid the groundwork in the 9th or 10th century. Usually, there's a name you haven't heard of waiting to be discovered.

- Support cross-disciplinary learning. If you're a developer, read philosophy. If you're an artist, study geometry. The "Golden Age" happened because people refused to put knowledge into tiny, isolated boxes.

- Visit the sites. If you can, go to the Alhambra in Spain or the astronomical observatories in Samarkand. Seeing the physical evidence of this intellectual height is a different experience than reading it on a screen.

The Golden Age of Islamic science wasn't a fluke. It was the result of a culture that prioritized curiosity, funded research, and wasn't afraid to learn from "the other." That’s a blueprint any society can follow if it wants to leave a mark on history.